Cotton is one of the most important commercial crops cultivated in India. It plays a major role in sustaining the livelihood of an estimated 5.8 million cotton farmers and 40-50 million people engaged in related activity such as cotton processing & trade. The Indian textile industry consumes a diverse range of fibres and yarn.

Soft, smooth-textured, light, airy, sheer and very comfortable fabric that comes in many forms and different avatars from coarse to real smooth, it has always been a favourite in different parts of the world. Which is that fabric? You guessed right, it’s Cotton.

The fibre that has been a favourite since the time it came into existence, it is cotton. The fibre is almost pure cellulose. Under natural conditions, the cotton bolls will increase the dispersal of the seeds. Over time it has evolved into a fabric that people can just not do without. It has its presence made in soft apparel for tiny tots to all kinds of clothing. Noted for its versatility, appearance, performance and above all, its natural comfort, it is literally everywhere – from apparel, including astronauts’ in-flight space suits, to sheets and towels, and tarpaulins and tents.

In fact, cotton in today’s fast-moving world is nature’s wonder fibre. It provides thousands of useful products and supports millions of jobs as it moves from field to fabric. Handloom Cottons are good plain weaves of simple lattice of closely placed yarn threads.

Cotton is one of the most important fibres and cash crops of India. It plays a dominant role in the industrial and agricultural economy of India too. Cotton is a major fibre crop of India as it provides for the livelihood of 6 million farmers and 40-50 million people are employed in the cotton trade and its processing.

There are several stages from the time the cotton seeds are planted to the time when the fabric is made ready. Let us trace this journey of cotton from seed to fabric.

Planting

Planting can be done manually as with easily available labour or by machine. The idea is to plant even and neatly in rows. Mechanically Planting is accomplished with 6, 8, 10 or 12-row precision planters that place the seed at a uniform depth and interval.

Young cotton seedlings emerge from the soil within a week or two after planting, depending on temperature and moisture conditions.

It takes about a month to a month and a half for the flower buds, generally creamy to dark yellow blossoms to emerge. Pollen from the flower’s stamen is carried to the stigma, thus pollinating the ovary. Over the next three days, the blossoms gradually turn pink and then dark red before falling off, leaving the tiny fertile ovary attached to the plant. It ripens and enlarges into a pod called a cotton boll.

Individual cells on the surface of seeds start to elongate the day the red flower falls off (abscission), reaching a final length of over one inch during the first month after abscission. The fibres thicken for the next month, forming a hollow cotton fibre inside the watery boll. Bolls open 50 to 70 days after bloom, letting air in to dry the white, clean fibre and fluff it for harvest.

Weed Control

Weeds could grow faster and shade cotton seedlings in spring when the cotton plants tend to grow slowly. If so, it could alter the yield adversely significantly.

Later in the season, cotton leaves fully shade the ground and suppress mid-to-late season weeds. For these reasons, weed control is focused on providing a 6 to 8-week weed-free period directly following planting.

Insect Management

When the cotton plant grows, as like with other plants, it evolves with numerous damaging insects as well that feed on squares and bolls. This reduces the yield and leads to delays in crop development, often into the frost or rainy season.

Some plants are improved by modern biotechnology, which causes the plant to be resistant to certain damaging worms.

Other bio-control strategies also are used. The more scientific approach of the cotton industry utilizes a multifaceted approach to the problem of insects. Known as Integrated Pest Management (IPM), it keeps pests below yield-damaging levels.

Plant Diseases

Cotton diseases have been contained largely through the use of resistant cotton varieties. Rotation to non host crops such as grain or corn also breaks the disease cycle.

Nematodes, while not truly a disease, cause the plant to exhibit disease-like symptoms. Nematodes are microscopic worm-like organisms that attack cotton’s roots causing the plant to stop growing, and as a result, causes reduced yield. Crop rotation is the primary method of managing for nematodes.

Soil Conservation

Cotton is sensitive to wind-blown soil because the plant’s growing point is perched on a delicate stem, both of which are easily damaged by abrasion from wind-blown soil. For that reason, many farmers use minimum tillage practices which leave plant residue on the soil surface thereby preventing wind and water erosion.

Conservation tillage, the practice of covering the soil in crop residue year ‘round, is common in windy areas. In the rain belt, land terracing and contour tillage are standard practices on sloping land to prevent the washing away of valuable topsoil.

Irrigation

The cotton plant’s root system is very efficient at seeking moisture and nutrients from the soil. From an economic standpoint, cotton’s water use efficiency allows cotton to generate more revenue per gallon of water than any other major field crop.

Cotton’s peak need for water occurs during July, when it is most vulnerable to water stress. A limited supply of irrigation water is being stretched over many acres via the use of highly efficient irrigation methods such as low energy precision applications, sprinklers, surge and drip irrigation.

Harvesting

While harvesting is one of the final steps in the production of cotton crops, it is one of the most important. The crop must be harvested before weather can damage or completely ruin its quality and reduce yield.

Harvesting is done by hands as well as by machine where spindle pickers are used cotton pickers pull the cotton from the open bolls using revolving barbed spindles that entwine the fibre and release it after it has separated from the boll.

Seed Cotton Storage

Once harvested, seed cotton must be removed and stored before it is delivered to the gin.

Seed cotton is removed and placed in modules, relatively compact units of seed cotton. A cotton module, shaped like a giant bread loaf, can weigh as much as 25,000 pounds.

Ginning

From the field, seed cotton moves to nearby gins for separation of lint and seed. The cotton first goes through dryers to reduce moisture content and then through cleaning equipment to remove foreign matter. These operations facilitate processing and improve fibre quality.

The cotton is then air conveyed to gin stands where revolving circular saws pull the lint through closely spaced ribs that prevent the seed from passing through. The lint is removed from the saw teeth by air blasts or rotating brushes, and then compressed into bales weighing approximately 500 pounds.

Cotton is then moved to a warehouse for storage until it is shipped to a textile mill for use. A typical gin will process about 12 bales per hour, while some of today’s more modern gins may process as many as 60 bales an hour.

In India, the process of separating the cotton fibres from the cotton seeds is more manual. The perfect ginning operation would be performed if the separation of fibres from seed was affected without the slightest injury to either seeds or to the fibre.

A cotton gin is a machine that quickly and easily separates the cotton fibres from the seeds, a job previously done by hand. These seeds are either used again to grow more cotton or, if badly damaged, are disposed of. It uses a combination of a wire screen and small wire hooks to pull the cotton through the screen, while brushes continuously remove the loose cotton lint to prevent jams. The term “gin” is an abbreviation for engine, and means “machine”.

Classing

After the lint is baled at the gin, samples taken from each bale are classed according to fibre strength, length, length uniformity, color, non-fibre content and fineness using high volume instrumentation (HVI) and the aid of an expert called a Classer.

Other quality factors also are important. The fibre’s fineness is important for determining the type of yarns that can be made from the fibre — the finer the cotton fibres, the finer the yarns.

Color or brightness of the fibres also is important. Cotton that is very white generally is of higher value than cottons whose color may have yellowed with exposure to elements before harvesting.

Cotton, being a biological product, typically contains particles of cotton leaves called trash. The amount of trash also influences the cotton’s value since the textile mill must remove trash before processing.

The fibre’s strength also is an important measurement that ultimately influences the fabrics made from these fibres.

Marketing

Cotton is ready for sale after instrument classing establishes the quality parameters for each bale.

The marketing of cotton is a complex operation that includes all transactions involving buying, selling or reselling from the time the cotton is ginned until it reaches the textile mill. Growers usually sell their cotton to a local buyer or merchant after it has been ginned and baled, but if they decide against immediate sale, they can store it and borrow money against it.

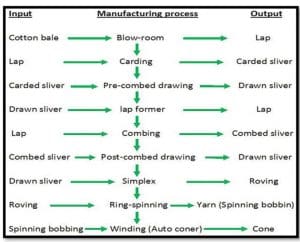

Yarn Production

Each processing stage in yarn manufacturing utilized the machine of specialized nature and provided quality effects in yarn production.

Fabric Manufacturing

Finally, different types of fabrics are manufactured from the yarn as follows

Non-woven product

Woven Fabric

Knitted Fabrics

Printed Fabric

Dyed Fabric

This Fabrics are Cut, shaped and combined to produced end product for final consumer.

—————————————————————————————————————-

Article by Ms. Hetal Mistry

B.Sc. Textile and Apparel Designing Department from Sir Vithaldas Thackersey College of Home Science (Autonomous), SNDT Women’s University – Juhu

Trainee Intern : Textile Value Chain

References:

https://www.barnhardtcotton.net/blog/the-journey-of-cotton-an-introduction/

http://www.internationaljournalssrg.org/IJPTE/2014/Volume1-Issue1/IJPTE-V1I1P104.pdf