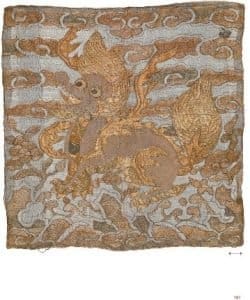

“Rank Badge with a Haechi” from 16th-17th century Joseon Kingdom / Courtesy of Sim Yeon-ok and Seo Heun-kang

Sim Yeon-ok traces 2,000-year history of Korean textile craft

Embroidery has a long history. The craft in Korea has evolved alongside textiles for over 2,000 years, reflecting cultural identity across historical eras and blurring the boundaries between art and technique.

Sim Yeon-ok, a professor at the Department of Traditional Arts and Crafts at the Korea National University of Cultural Heritage, published her third book “2,000 Years of Korean Embroidery” to shed light on the lesser-known mastery of Korean embroidery.

While previous research on Korean embroidery focused on aesthetics, Sim, as a textile engineer, looked at embroidered works through a microscope to examine their details and structure. Sim said her former professor Min Gil-ja, a pioneer in Korean textile research, inspired her to delve into the field.

“Fiber and textiles should be understood and researched from an engineering perspective, as structural design is inseparable from the creation of fabric. Most of Korea’s clothing history was studied by historians and domestic science majors, who did not have much knowledge of engineering,” Sim said. “Professor Min encouraged me to study in China as understanding Chinese textiles was essential for studying Korean textiles considering the exchange between the East Asian countries.”

Sim Yeon-ok, professor at the Korea National University of Cultural Heritage

Sim went to the China Textile University in Shanghai, now Donghua University, in 1992, right after diplomatic ties between China and Korea were established. “I am one of the first South Korean doctoral students in China,” Sim said.

“Ornamental Pendant” from Goryeo Kingdom using split and blanket stitches / Courtesy of Sim Yeon-ok and Seo Heun-kang.

Sim’s devotion to Korean textiles is represented in her previous books “5,000 Years of Korean Textiles” (2002) and “2,000 Years of Korean Textile Design” (2006).

“My first book was inspired by Jennifer Harris’ book 5,000 Years of Textiles. This book encompasses the history of textiles worldwide, but Korea is not even mentioned. So I researched the history of Korean textiles extensively, finding its place in the overall history of textiles,” Sim explained.

“The history of textiles in Korea is 5,000 years old because the oldest spindle whorls, which signal the beginning of weaving and textiles, found on the Korean Peninsula are 5,000 years old. Most significant relics related to the history of textiles exist in Korea and I was able to tie Korean textiles in with world history.”

Her interest shifted to embroidery, a field that has not been studied deeply in Korea’s textile history.

“When Sudeok Museum of Sudeok Temple in Yesan, South Chungcheong Province, held an exhibition on embroidered Buddhist treasures, I was asked to write a piece for its catalogue. Despite the amount of embroidered relics, there was barely any research on it and almost none in English. As I studied embroidery further, I made many fascinating discoveries including the way our ancestors saved expensive silk threads for satin stitches and used different stitching techniques,” Sim said.

The book features 48 Korean embroidery works from the Ancient Kingdoms era dating back as far as the 1st century A.D. to the relatively recent Korean Empire of the early 20th century. Sim collaborated with one of her students, Keum Da-woon, to write this comprehensive book on the history of Korean embroidery.

“Korea’s climate and soil are not suitable for preserving organic matter, including fabric and thread. Most of Korea’s intact embroidered works are from after the 14th century and earlier works are in fragments,” Sim said. “However, documents exist on weaving fabric and embroidering on it, giving a glimpse into ancient embroidery. We also can reference Chinese documents on patterns since East Asian countries exchanged influences.”

The oldest embroidery found on the Korean Peninsula is the “Fragments Embroidered with Swirling Cloud,” dating back to the 1st or 2nd century A.D. Excavated from Seokam-ri Tomb no. 9 in Pyongyang, the remnants show how ancient Koreans used chain stitching to portray lines and planes.

“The tombs were excavated by the Japanese in the early 20th century and only photographs of these embroidered fragments exist now. I tried to trace and research actual objects as much as possible, but was not able to find this one except for the photos,” Sim explained. “Back then, chain stitching was popular throughout Asia and the ancient people embroidered with extremely fine threads.”

Another notable discovery for ancient Korean embroidery is the “Embroidered Lining of Gilt-Bronze Shoes” from the Tomb of King Muryeong, who ruled Baekje Kingdom from 501 to 523, in Gongju.

“There were more embroidered works remaining than expected as some of them are not categorized as embroidery,” Sim said. “For this pair of gilt-bronze shoes, braid and loop stitches were used on gold. Though it is now discolored, it used at least two colors of dyed yarns, which would have been very vivid originally.”

The “Tenjukoku Mandala,” currently in the collection of the Chuguji in Nara, Japan, is believed to be created by Korean embroiderers.

“This shows that Korean embroidery was highly advanced and its influence reached overseas,” Sim said.

Sim also found the use of split stitching in ancient Korea through the “Banner from Silla,” featuring a dragon with palmette pattern. “The split stitch is similar to the chain stitch and often mistaken for it, but it was widely used in East Asia,” she said.

Sim and her team also analyzed all stitches used in the “Fragrance Pouch” from the 10th century Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392), which was found in the Nine-Story Octagonal Stone Stupa at Woljeong Temple.

“It was embroidered on a complex gauze fabric named ra, which no longer exists. However, there are records of embroidering on ra fabric, so understanding the ground fabric was the first step,” she said. “The pouch employed multiple stitch techniques including straight, satin, split, couching and applique. The chain couching technique, now discontinued, is only found in this embroidered work, while the applique stitch was popular in China as well.”

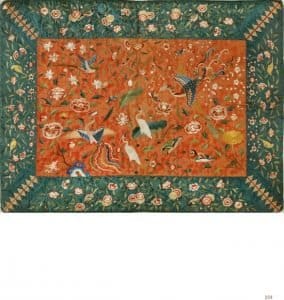

“Seat Cushion with Landscape of Lotus Pond and Phoenixes” from 17th century Joseon Kingdom / Courtesy of Sim Yeon-ok and Seo Heun-kang

Embroidered Buddhas demonstrate another important use of embroidery. “Amitabha Buddha” from the late 14th century used counted stitches to portray skin texture.

“Kasaya Attributed to the Monk Bojoguksa” of Songgwang Temple was lost during the 1950-53 Korean War and only a glass dry-plate photo of it is in the collection of the National Museum of Korea. Sim discovered a twin of the kasaya in Japan ― “Folding Screen with an Embroidered Kasaya Composed of Nine Strips of Patchwork.”

“Though the Korean one only exists in photographs, it seems that both kasaya were used the same fabric, motifs and details, hinting that they were made by the same craftsperson around the same time. Using the knot stitch to depict the body of a dragon is a unique use of the technique and found in both kasaya,” Sim explained.

Embroidered relics from Joseon era remain in more intact and original form.

Sim picked the “Rank Badge with a Haechi” from 16th-17th century Joseon as one of the most charming objects in the book. A haechi is a mythical creature resembling a horned lion, often considered a protector of the capital.

“This is embroidered on as fabric, or simple gauze. Since the simple gauze is sparsely woven fabric, it is highly transparent and you can see through it. It best represents the beauty of space in Korean embroidery,” Sim said. “Though now the threads are discolored mostly to brownish, imagining it in its original color is just fascinating.”

The “Rank Badge with Clouds and a Pair of Geese” from the Seok Juseon Memorial Museum of Dankook University is a well-known embroidery piece and Sim at first thought of skipping it for this book.

“However, when I looked at it using a microscope, I was amazed by luxurious details of the piece. Its background is tabby silk with gold thread wefts and it featured over 20 kinds of colored threads, mixing horizontal and vertical stitches to give a 3D effect,” Sim said. “Embroidering on gold fabric could change the textile history of Korea and this is why microscopic study is important in textiles.”

Detail of “Rank Badge with Cranes” from 17th century Joseon Kingdom / Courtesy of Sim Yeon-ok and Seo Heun-kang

Sim hopes her book would shed light on the history of Korean embroidery as well as embroiderers who keep the techniques alive.

“Most Korean embroiderers are very skilled, but they only learn and pass down the techniques in apprenticeship without proper understanding of its history. I hope Korean master embroiderers would have confidence in their skill and work, which comes with a history of 2,000 years,” Sim said.

Sim has devoted her life to research on Korean textiles and now broadens her horizon to weaving.

“Mosi, or Korean ramie fabric, is recognized by UNESCO as an important Intangible Cultural Heritage, but Koreans, especially the young generation, do not know it well nor wear it. I want to modernize it,” Sim said. “We have a manual Jacquard loom at our school and I am experimenting with weaving patterned mosi fabric so it could reach the younger generations.”