Monforts Head of Technical Textiles Jürgen Hanel outlines the development of the textile coating industry and the fundamental principles behind today’s advanced coating processes.

Humans are the only primates without fur to protect themselves from the elements and first used animal skins and furs to shield themselves from either the cold or from UV radiation, depending on where they were in the world.

Over 5,000 years ago, fabrics woven from plant fibres and wool were then developed, bringing many advantages such as their warmth, softness and breathability, as well as UV-shielding, and the development of dyeing gradually gave rise to the concept of fashion.

There remained, however, a problem – protection against rain for those in wet climates, and later, for seafarers. Furs and leather were still widely used for this purpose until very recently.

Waterproofing

It took until the 19th century for a workable solution to finally be developed by the Scottish textile manufacturer and inventor Charles Macintosh, although waterproofing garments with rubber was not a new idea, having been practiced by the Aztecs in pre-Columbian times.

Later, French scientists made balloons gas-tight and impermeable by impregnating fabric with rubber dissolved in turpentine, but this solvent was not satisfactory for making apparel.

Macintosh too, first impregnated a thick woollen fabric with a solution of natural rubber. The result was waterproof but stank of petroleum and was sticky due to the wool grease.

Only when a method was developed for coating the fabric on one side and heating the rubber in a dryer with the addition of sulphur – the process of vulcanization – was the Macintosh coat fabric ready for commercialisation.

How the fabric was coated and in which drying oven it was vulcanized is unfortunately not known, but this development formed the basis for textile coating as we know it today.

Air knife coating

There are two fundamentally different basic coating processes – air knife coating and roller knife coating.

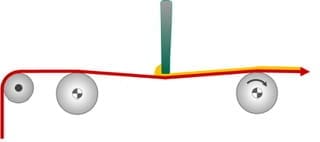

In air knife coating, a squeegee blade brushes over the surface of the textile, pressing the highly viscous coating paste into the spaces between the material.

It is impossible to coat low-viscosity chemicals with this method or the paste will drip through the meshes/weave interstices.

Air knife coating, however, is used firstly wherever sealing of the fabric is required, for example on umbrellas to prevent spray mist getting through to the inside. Other examples include shower

curtains, rainwear, bag and rucksack fabrics, tents etc.

Air knife coating is also used for mattress tickings and upholstery fabrics. In this case a back coating is applied which has a double function – the material is made liquid-tight and in addition it is fixed. In the case of upholstery fabrics, this fixes the pile, but can also be used to achieve technical effects such as flame protection.

In fashion and decorative articles, air knife coatings are also used for one-sided colouring, while textile materials for shoes are coated to make them waterproof.

Technical textiles

The areas of application with the air knife coating of technical textiles are extremely diverse, ranging from filter fabrics to textile seals and to carbon fibre impregnation.

In addition to coating with a thickened paste, there is also air knife coating with foam. In this case, physical foam is produced in a special foam machine (similar to whipped cream) and placed in front of the coating knife. The foam is pressed into the fabric by the knife and the foam is destroyed.

This so-called unstable foam coating is used, for example, for over-dyeing jeans. In a coloured/colourless version, nonwoven fabrics are also fixed and overdyed in this way.

The term “unstable” does not mean this is bad foam. Unstable foams remain stable below room temperature for at least five minutes and do not decompose, but the air bubbles then burst under the knife, or at the latest when the foam is subsequently heated in the dryer.

Foam coating with the air knife has many advantages – by diluting the coating chemical with air, less drying power is required, and the penetration depth is lower, while the breathability of the textile is maintained.

Roller knife coating

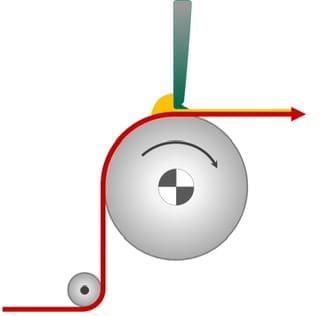

In roller knife coating – also called roller nip coating – the application with the knife is practically flying, without touching the upper side of the textile.

This has various effects on the final product. The application in the nip, for example, covers the surface of the textile with the coating compound to give this side of the fabric a plastic-like surface, which is determined by the chemistry used.

Well-known examples of roller knife coated fabrics are tarpaulins, life jackets, carpet backing, upholstery fabrics, trunk covers, sealing materials and many others.

Roller knife coating places very high demands on the precision of the machine, in contrast to air knife coating. Nevertheless, combinations of these two coating types are mainly offered today.

For this purpose, the coating knife bar is designed to be horizontally adjustable and the precision achieved depends on the supplier of the coating machine.

The roller knife can be used in the same way as the air knife with paste, for example in the coating of PVC tarpaulins, emergency slides, inflatable boats and sealing mats.

Both unstable and stable foams are used in roll knife coating. If a layer of unstable foam is applied, it decomposes in the first zones of the dryer.

The roller knife coating of unstable foams (also referred to as “metastable foams”) is used in the production of jeans to dye over the denim material on one side, for example. By applying the coloured foam on the surface, a good over-dyeing is achieved, which can be washed out easily in industrial laundering to achieve the desired “stonewash” effects.

Stable foams survive the drying process in the dryer (under very mild drying conditions) and leave the dryer as a foam layer.

Black-out fabrics

A good example of an application for roller knife coating with stable foams is in the production of black-out fabrics for blinds or curtains. These products require special treatment in order to retain the softness of the fabrics and to ensure that it is still possible to wind blinds up and down.

A special coating called Black-Out has been established to achieve this, involving a three-stage series of stable foam coatings with the roller knife.

The first coating is usually white, followed by a black layer and then a white layer again. These three layers are dried and are with a crush calendar after each layer is applied. A fourth dryer passage then cure all three layers together with the possible addition of a last topcoat to improve the grip.

This process is complex and expensive, and mistakes can result in the entire production run being rejected, so experienced and trained personnel are required.

A similar process is used in the production of advertising banners, which is called ‘block-out’. This is a multi-layer foam coating to prevent the image/text of the banner from showing through on the back side of the material.

Rubber coating

Let’s return here to the Macintosh and coating with rubber, as a rather amazing application for roller knife coating.

The applied rubber layer is so waterproof and airproof that such materials can also be used for lightweight boats, life rafts, life jackets and emergency slides in aircraft.

However, such basic waterproof fabrics have a problem in apparel, in not allowing the moisture generated by the wearer to escape.

Consequently, the textile industry was challenged to develop a material that would repel rain, but at the same time be breathable for the wearer.

Probably the first product to meet this challenge was (and still is) marketed as Gore-Tex® for outdoor clothing. Gore-Tex®, however, is not a coated fabric, but a waterproof, breathable membrane that has been laminated.

The availability of water vapor permeable polyurethane dispersions also allowed direct coating on the inside of the fabric. This is where roller knife coatings are applied. Depending on the required stress, stable foam coatings and also paste coatings are used.

Lamination

Lamination is generally understood to be the joining together of two or more layers of textile, film, membrane or fleece and to keep the layers together an adhesive is needed, which can be applied by either coating or screen printing.

A distinction can be made here between dry or wet lamination.

In wet lamination, the adhesive is initially applied to the first layer and the second layer is then placed in the wet application before the two materials are dried and fixed together.

The disadvantage of this process is the hardness/rigidity of the laminated end product.

In dry lamination, the adhesive is applied to the first material and dried and the second layer is then applied to it via high pressures, usually by a calender.

A special case is that of stable foam lamination.

In this process, a layer of foam is applied by a roller doctor blade and carefully dried. The second layer is then placed into the dry foam by a crush calender. Afterwards, however, this laminate must still be thermally fixed. Foam lamination has the softest touch and in the case of polyurethane foam the laminate is also thermally resistant, as the adhesive is not thermoplastic after fixing.

Conclusion

In this article I have tried to provide an overview of the technology of textile coating and would like to conclude by listing just some of the coated materials that are to be encountered in daily routines.

We can start with the mattress cover, slippers, the shower curtain and the bathmat and move through to the dining table with its coated tablecloth, then out to the hallway for a rain jacket and umbrella. In the car, countless more coated fabrics are to be found, from the seat cover to the trunk, and just as many coated materials will be encountered by commuters using trains or buses.

Textile coating is still a technology of the future with which money can still be made. With the increase of lightweight construction, just as one example, fibre reinforced materials are becoming increasingly important. Here, textiles or fibre scrims are only used to reinforce the plastic matrix, but the technology of production is similar and therefore represents another growth area for textile coating.