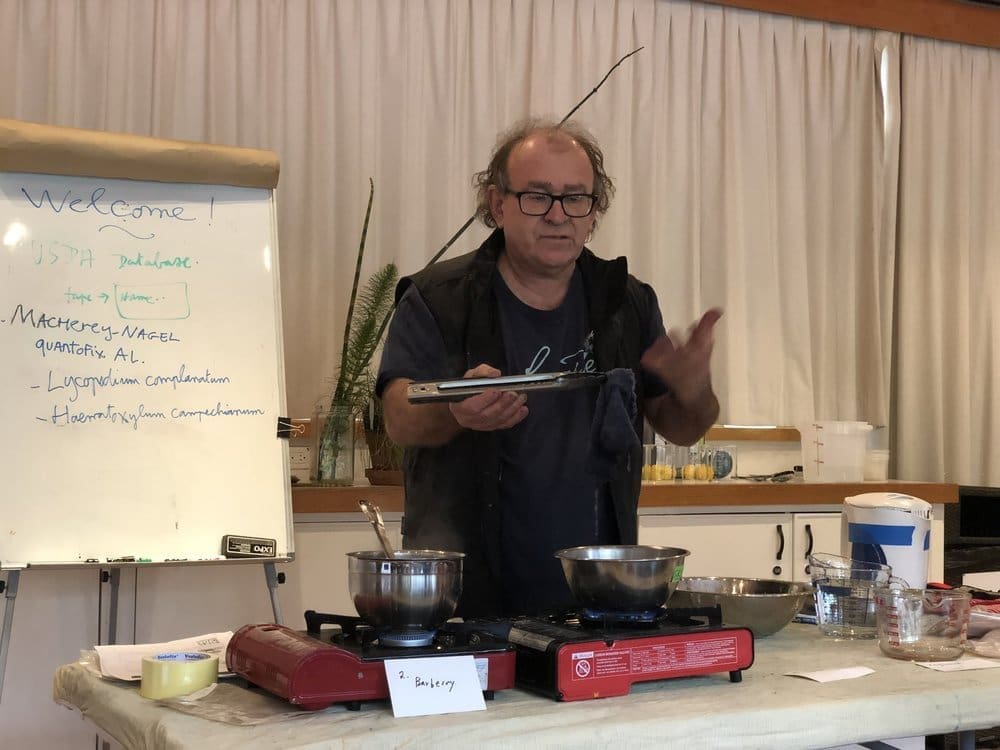

Michel Garcia demonstrating natural mordants and dyes.

UC Botanical Garden in full bloom.

I learned that Lycopodium complanatum is a bio accumulator of aluminum and was used by native people across North America, Northern Europe and Scandinavia to fix natural dye to fiber. Where I live we find Princess Pine (Lycopodium obscurum), a type of clubmoss, growing in the Gifford Pinchot Forest. I am excited to forage, dry, chop and test it out. A simple test is a 2-step process mordanting the fiber in Lycopodium and then dyeing it in Logwood. If the fiber turns blue then the Lycopodium has accumulated the aluminum. Symplocos is another well-known bio accumulator of aluminum but it doesn’t grow in my area. I may purchase some and try it out to see the various colors it yields and how similar or different they are compared to Lycopodium.

Lycopodium, logwood.

Lycopodium, logwood, barbery.

Lycopodium plant at the UC Botanical Garden.

We used the Berberis species as a mordant for a diversity of natural dyes, including logwood and madder. More importantly we talked about how the Mahonia species behaves the same as Berberis in that the tannins in the bark act as a natural mordant producing a beautiful yellow. I have a lot of Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium) growing on my property and especially after the harsh winter I have some downed limbs so I am going to harvest, dry, grind and test away.

Barberry, madder.

Barberry.

I have always been curious about using roots from reeds/grasses and Acorus calamus commonly known as sweet flag is a color enhancer/binder in combination with other natural dyes. Michel used Sanguinaria Canadensis (bloodroot) with the sweet flag. I have been thinking about growing it in my new dye beds that I will be adding this year. Not only does it have a beautiful flower it also produces a stunning color.

Sweet flag, cochineal.

Sweet flag, bloodroot.

Invasive species are an issue everywhere and I have always been curious if there is a way to harness something purposeful and beneficial from them. In my area we have issues with Knapweed and I wanted to test it out to see if I could produce color for which it did create a beautiful array of colors. I was very careful not to let the plant get caught in the wind on my property but sure enough the season after I tested it I found five little plants taking hold on my property. Luckily I got them pulled before any signs of flowering. This cautionary tale makes me nervous about bringing horsetail (Equisetum arvense) onto my property given its invasive quality, although I am in a dry, hot climate so I doubt it would take hold. I would love to experiment with it so maybe I will collect some from the Oregon Coast. Again horsetail like sweet flag is a color enhancer for a variety of natural dyes. It contains natural silica that abrades the surface of the wool.

Horsetail, madder.

Horsetail, pagoda tree flower.

Finally Michel demonstrated the power of tannins as a mordant. I have used tannins a lot in the dye studio because I like to dye on cellulose fiber and I dye with mushrooms for which tannins can enhance and change the color of mushroom dyes. When tannins are combined with either lemon juice or citric acid they create an array of colors. We used acid because we were working with wool but if we were using cellulose fibers we wouldn’t want to do this! I learned that rowan berries (Sorbs aucuparia), commonly known as mountain-ash or rowan, are a great source of tannins and enhance colors. Using the root of rhubarb works very well and Michel mentioned he doesn’t ever have much success from using rhubarb leaves. He even demonstrated an experiment I stumbled on a few years back when I was trying to produce a purple/pink from st. john’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) using tannins and citric acid instead of using aluminum, which yields the standard yellow.

Myrobalan, lemon juice, alkanet.

Tannins, citric acid, rhubarb.

Tannins, lemon juice, cochineal.

Tannins, citric acid, st. john’s wort.

Tannins, citric acid, buckthorn.

Tannin, citric acid, rowan berries, madder.

Michel Garcia is a wealth of knowledge and incredibly generous in sharing his expertise. He encourages everyone to experiment and discover on their own. He doesn’t have recipes, he doesn’t measure, he just knows! It is a joy to learn from Michel but I also really enjoy meeting other natural dyers. There were 15 of us in this session so we all got to talking about what we have been experimenting with in our dye studio, the things we learned and our shared passion for plants, art, science and color. Michael from the Bay Area mentioned that the Camellia japonica species is a huge bio accumulator of aluminum and he has had a lot of success using the leaves. When I lived in Portland I had the largest, most stunning camellia tree in my yard. I am thinking of knocking on the new owners door and seeing if I could collect some leaves. Nari from San Francisco sat next to me and we researched information online as we were taking notes during Michel’s demonstration and shared what we learned afterwards. Debra from @circleoflifestudio in Wisconsin was delightful and we toured the natural dye exhibition together that was on view.

And of course, no visit to Berkeley is complete without a visit to A Verb for Keeping Warm @avfkw where they naturally dye all their own fiber! I have followed them for some time on Instagram. I inquired about their indigo harvest and learned today there is an indigo book coming out someday in the future!

Naturally dyed fiber.

Reference:https://www.bloomanddye.com/journal/2019/3/28/dyeing-with-natural-mordants