What do the British Redcoats, Cardinal Red, Incan ‘blood’ Red have in common? All of these “royal” red cloths obtain their natural-dye colorant from the small insect cochineal (Dactylopius coccus)—its size about a grain of Arborio rice. Living on cacti, primarily in the Oaxaca area of Mexico and between the highlands and coast in the Andes, the female cochineal insect produces carminic acid, a deep crimson dye.

During my last visit to Peru, we stopped at the weaving village of Acopia. It was dye day. And not just any dye day, but red dye day. The shades of red emerging from those pots couldn’t be more vivid. The weavers dye their own handspun wool and alpaca yarns for weaving their own cloth. So during the day, they were checking their colors, adding a few skeins to different baths, ensuring they would have a wide range of raspberry to scarlet reds, to fuchsia and purples.

Some History

Originating in the Americas, cochineal, along with gold and silver, was considered by the Spanish as one of the great treasures of the New World. During the 16th-18th centuries, cochineal was shipped by the tons back to Spain and from there, to many regions in the world. While the vast majority was used for textiles, it also was used by artists in paint glaze and pigments to make strong blacks. Today, it is still one of Peru’s largest exports.

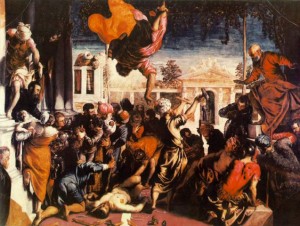

Miracle of the Slave by Tintoretto (c. 1548). The son of a master dyer, Tintoretto used Carmine Red Lake pigment, derived from the cochineal insect, to achieve dramatic color effects (Wikipedia: Pigment)

Cochineal is certainly not the only natural dye that produces red, or shades thereof. However, it is the one mostly used in the Americas. Plant roots such as alkanet and madder, the dried fruit myrobalan, or other insects related to cochineal such as kermes and lac, are all used for natural red in other parts of the world.

The Insect and the Nopal Cactus

Cochineal insects have a flat, soft body, and oval-shaped scale. The females cluster on cactus paddles, feeding on its juices. After mating, they give birth to nymphs that secrete a waxy white substance over their bodies for protection. It’s this substance which makes the insect appear white or grey on the outside and its inside a dark purple.

Cochineals can be farmed traditionally by planting infected cactus pads or infecting existing cacti with cochineals and harvesting the insects by hand. Or farmed by a controlled method, small baskets, called Zapotec nests, are placed on host cacti. The baskets contain clean, fertile females that leave the nests and settle on the cactus for mating.

To produce dye from cochineal, the insects are collected when they are about 90 days old. They are individually knocked, brushed, or picked from the cacti, and killed by some form of heat. It takes about 100,000 insects to make one kilo of cochineal dye.

Dyeing with Cochineal

A little of this bug goes a long way–100 grams will dye about two pounds of fiber to a deep shade and will set you back about $25-30. It takes readily on wool and silk, but will also dye cotton using more dyestuff. There are many excellent cochineal dye recipes available and you can find cochineal bugs from many sources.

When dyeing with cochineal, the whole insect gets ground into a fine powder. This powder is then dissolved in a large pot of simmering water. The pre-mordanted fiber goes into the dyebath, and depending on what mordant was used, fuchsia, bright red, and purples start to emerge. An ammonia afterbath pushes the color toward purple, and tartaric acid, such as lime juice, towards orange-red.

Weavings Using Cochineal

Start the hunt for cochineal red used by artisans in the Americas in Tenejapa, Chiapas, they weave brocade fabric–the wool is dyed. In the Chinchero village of Peru, the alpaca and wool warp is spun and dyed. See examples here.

So the next time you toss back that Campari or add the luscious shade of red to your lips, thank this little female insect.

Special Resources and Thanks

A number of artisans and educators have contributed one way or another to this blog: Demetrio Bautista Lazo, a rug weaver from Oaxaca, Mexico, who designs and weaves naturally-dyed rugs (you can read more about him in Interweave’s Colorways 2011 e-magazine); José Jiménez, ikat weaver from Ecuador, the Peruvian weavers of the Center for Traditional Textiles of Cusco; Elena Phipps, curator and author of Cochineal Red; The Art History of a Color (you can learn more by watching her on YouTube here); Olga Reiche, natural dye author, teacher, and weaver from Guatemala, and Michele Wipplinger of earthues, natural dye author, teacher and supplier of dyestuffs. Thanks to photographers Robert Medlock and Joe Coca for supplying images.

Reference: https://www.clothroads.com/cochineal-the-royal-red-of-natural-dyes/