In the C19th the north eastern Yoruba and their neighbours wove large quantities of cloths which were traded to the north. Among the central Oyo Yoruba and in northern Nigeria women’s weaving overlapped with that of men using the double-heddle loom, but in other districts, in particular among the Igbo in eastern Nigeria women were the only weavers.

Rare style of Ijebu cloth, circa 1900.

Rare style of Ijebu cloth, circa 1900.

In the years since the 1950s this kind of weaving has declined drastically in both the Yoruba and Igbo speaking regions of Nigeria, partly because it is an extremely slow and laborious process, but also because women now have wider opportunities for trading, education and other careers. In the south of Nigeria it only survives today on a very small scale in a few areas where local specialisations are still in demand, notably in the Yoruba town of Ijebu-Ode, and far to the east in the Igbo village of Akwete. In central and northern Nigeria, where there has been less development, the picture is brighter. There are still a relatively large number of women using these looms in the Ebira town of Okene, the Nupe capital Bida, and in Hausa cities, particularly Kano. Although these are largely traditions in decline (including in Okene in the past few years,) fine examples of older cloths can still be found, and where the weaving continues, as in Akwete, some very high quality new cloths are woven for local use.

Ijebu-Ode: The capital of the ancient Yoruba speaking kingdom of Ijebu, i ts women weavers produce a distinctive style of highly ornate cloth known as aso olona, cloth with decorations or art. Bands of weft float decoration representing designs such as crocodile, frog, elephant, and koran board, are alternated with bands of shaggy pile weave. These cloths are worn as insignia of office by members of a once powerful association of elders known as Oshugbo (or Ogboni). The earliest known example of this type of cloth, in the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, dates from as early as 1790. The cloths were once traded along the coastal lagoons to the Niger delta region where they became known as ikakibite or “tortoise cloth” and highly prized in local rituals. Akwete Igbo women weavers then p r o d u c e d s i m i l a r d e s i g n s , a l t h o u g h t h e y a r e c l e a r l y distinguishable by the wider panels woven.

Akwete: This small town just north of the city of Port Harcourt is one of the last centres of a once much wider tradition of Igbo women’s weaving. It is famous throughout eastern Nigeria for the quality of the cloths produced there which are highly prized for the Igbo women’s ceremonial dress known as “Up and Down”, in which two cloths are wrapped around the body, one at the waist, the other under the arms. Akwete women use a uniquely wide version of the loom, allowing a single width of cloth to form a women’s wrapper. Among the huge range of designs produced is a version of the Ijebu aso olona, which they have woven since at least the C19th for sale to the Ijaw people of the Niger Delta to the south.

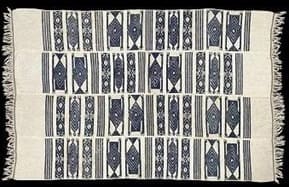

Fine mid C20th Nupe cloth

w o m e n w e a v e h i d d e n i n t h e passageways of labyrinthine mud- walled compounds to which non- family men are forbidden entrance. Among the textiles they wove in the past are elaborate marriage cloths known as “duna”, and some beautiful predominantly red wrapper cloths.

the Northern or Akoko Edo are a culturally diverse range of peoples living in small villages . Alongside a lot of very obscure and localised traditions of cloth decoration, they wove fine indigo wrappers from hand-spun cotton. The picture shows senior women from the royal family in a small village called Somorika wearing locally woven cloths, some of which mix hand spun cotton with white linen- like thread called “ebase” obtained from tree bark.

TEXTILES OF BURKINA FASO

Burkina Faso is the biggest African cotton producer and exporter, so it is no surprise that it boasts a strong textile heritage of handwoven cotton fabric, traditionally called Danfani. Stripes are the signature style of handwoven Burkinabé fabric however artisans are able to weave complex tartan and hounds-tooth fabric designs. Preparing the design on the loom itself can involve three to seven days of work depending on the complexity of the design. Artisans can weave on small and wide looms, the latter makes the fabric more attractive commercially as fashion & design buyers can do more with this larger fabric.Burkina Faso was the first African country where a GM crop was principally grown by smallholder farmers. The crop was an insect-resistant cotton variety, developed through a partnership with the US-based agri-business company Monsanto (now Bayer CropScience). At its height nearly 150,000 Burkinabè households grew GM cotton.

Dan Fani

The Faso Dan Fani is a woven cotton cloth made in the West African, landlocked country known as Burkina Faso. A cotton-based textile isn’t a novel addition to this series. Neither is a fabric that is weaved on a loom nor made up of several strips combined together. What makes this cloth special is its connotation. When former president Thomas Sankara became president in 1983, the Faso dan Fani (FDF) became a national symbol.“To wear the Faso Dan Fani is an economic, cultural and political act of defiance to imperialism,” said Thomas Sankara in 1986. “”In every village in Burkina Faso, we know how to grow cotton. In all the villages, women know how to spin cotton, men know how to weave this thread in loincloths and other men know how to sew these loincloths in clothes. We must not be a slave to what others produce.” He made it mandatory that the Faso Dan Fani be worn in the workplace.