Turkey, officially the Republic of Turkey is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian peninsula in Western Asia, with a smaller portion on the Balkan Peninsula in South-eastern Europe.

Turkey, country that occupies a unique geographic position, lying partly in Asia and partly in Europe. Throughout its history it has acted as both a barrier and a bridge between the two continents. It is among the larger countries of the region in terms of territory and population, and its land area is greater than that of any European state.

Culture

Turkey has a very diverse culture that is a blend of various elements of the Turkic, Anatolian, Ottoman (which was itself a continuation of both Greco-Roman and Islamic cultures) and Western culture and traditions, which started with the Westernisation of the Ottoman Empire and still continues today. This mix originally began as a result of the encounter of Turks and their culture with those of the peoples who were in their path during their migration from Central Asia to the West. Turkish culture is a product of efforts to be a “modern” Western state, while maintaining traditional religious and historical values.

The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul

Turkish Textiles

One great way to see the cultural distinctiveness of any nation is through its clothing and the fashions people wear. Clothing is manufactured from textiles or fabrics and cloth made from natural and/or synthetic fibers. Turkey, formerly known as the Ottoman Empire, has a history that stretches back to antiquity, and their textile industry goes back just as far.

While Turkey was the Ottoman Empire (1299 through 1922), textiles were an important part of their economy and a feature of the nobility. Any textile sold was a part of the empire’s treasury which in those days belonged to the sultan (king) and royal family. In this way textiles and the wealth of the sultan were interchangeable illustrating the importance of textiles in the Ottoman Empire. This fact also indicates that Ottoman textiles had to be of high quality, and were considered to be a luxury item.

Turkish Carpet 11th – 13th Century

Carpet weaving is a traditional art from pre-Islamic times. During its long history, the art and craft of the woven carpet has integrated different cultural traditions. Traces of Byzantine design can be detected; Turkic peoples migrating from Central Asia, as well as Armenian people, Caucasian and Kurdish tribes either living in, or migrating to Anatolia, brought with them their traditional designs. The arrival of Islam and the development of Islamic art also influenced Turkish carpet design. The history of its designs, motifs and ornaments thus reflects the political and ethnic history and diversity of Asia minor. However, scientific attempts were unsuccessful, as yet, to attribute a particular design to a specific ethnic, regional, or even nomadic versus village tradition.

Textile Production

As far back as the year 1502, Busra was the hub for the Ottoman Empire’s textile market, and as all textiles belonged to the royal family their sale and manufacture were controlled by the state. Any Turkish textile merchant had to follow rules and procedures to sell their wares in Busra, and those who disobeyed these laws were met with swift retribution. The rules all textile merchants adhered to were found in the ihtisab kanunameleri, and most of the procedures listed in this manual were explicit in their requirements.

No silk merchant could follow their own devices for weaving silk as everything from the materials used, the thread count of the silk fabrics, and the weight of the textiles created was strictly monitored. Merchants couldn’t even use their own gold and silver embossment threads as these too were monitored by the state and manufactured in state run textile workshops called simikeshaneler. Any threads used for this purpose had to have the endorsement of the government, or never made it to the Busra marketplace for sale.

As soon as garments (especially silk) were finished they had to be sent to state officials called muhtesip to be ironed, measured and inspected. Muhtesips ensured that all rules and procedures of the ihtisab kanunameleri were adhered to before any textile could be sent to Busra for sale.

This type of rigorous supervision facilitated the high quality of all Turkish textiles. It also provided for the creation of textiles that were distinctively Turkish and unlike any others produced the world over.

Turkish Mirror Cover 18th Century

The Turkish state classified all textiles into three groups of cotton, wool, or silk. This was important due to the fact that most cotton and wool textiles in the 15th through the 17th centuries were imports. Cotton was obtained from India, and wool (mainly used for soldier uniforms) came from Europe.

However, mohair production was something that the Turkish prided themselves on and was made from the hair of angora goats found in the Ankara region of the country. Mohair was very soft and silky, just like the hair of the Angora goat, but when mixed with wool could be used to create clothing. Mohair exports did very well abroad, especially in Europe.

Angora goat

Turkish Silk

Nevertheless, when it came to textile production nothing compared to silk for the Turkish. Also found in Busra was the silk worm used to obtain the silky yet strong fibers used to create silk. Even more than the capital of Istanbul, Busra cornered the market for silk production and trade.

The Turkish have mainly worked with silk extracted from silk worms that they then embossed or trimmed with gold and silver threading. Turkish textiles can also double as works of art as gold and silver designs of tulips, date palm trees, or the Islamic crescent moon and star can be seen in many examples across periods.

Many different textile hybrids can be made from silk ranging from taffeta, satin, velvet, and brocades. Excellent weavers of silk, the Turkish created works of art that exceeded clothing. For example, Turkish brocades that they called kemha could have embroidered gold and silver flowers and celestial bodies which adorned furniture cushions, carpets, and even mirrors that date back to the 16th and the 17th centuries.

Kemha fabric

Ottoman Brocade 16th Century

Colour, Design and Painting in Traditional Arts

Design:

Designs, the result of prevailing environmental conditions, are the cultural language and source of art. These symbolic designs reveal the characteristics of a society in social research.

The Turks continued to live in clans and tribes after migrating to Anatolia. After a long period of different beliefs, they finally turned to Islam but the heritage of the old beliefs, legends and myths are still alive and can be seen in various symbols that are used in the decorative arts today.

Design is the main component of ornamentation. In Anatolia, designs are known by different names, such as motif, im, yanis and nakis.

Different designs exist in all branches of traditional arts depending on the place, purpose of use or message contained. These may be vegetal (trees, flowers, fruits etc.), animal (birds, butterflies, horses, wild animals, snakes, scorpions etc.), objects (for daily use), figures (inspired from daily life etc.).

Colour- Painting:

Colouring is one of the oldest arts, the history of obtaining dyes from natural sources going back thousands of years.

It is true that human beings respect and admire the colours that exist in nature. The relations between man and plants are a very old one. Early man not only used plants to feed himself, but also used leaves as a covering.

People realized the impossibility of coloring textiles with undissolved substances, and so used the root, body and leaves of plants. Besides plants, some dyes were also obtained from animals.

In Anatolia during the Ottoman period, coloring materials were exported until the 19th century, although the invention of synthetic dyes had a severe impact. Today, a few educational institutions in some regions are trying to keep the tradition of natural dyes alive.

People have considerable knowledge of natural dyes in some regions of Anatolia, especially those where rugs and carpets are produced. Families involved in rug-making keep such information on dyes a closely guarded secret.

The material “mordan” is used to prepare the object for coloring and help the object maintain its colour. Arborvitae is the most commonly used kind of mordan in Turkey. Studies have shown that, red, green and yellow have historically been the most widely used colors.

Traditional Turkish handicrafts

Traditional Turkish handicrafts form a rich mosaic by bringing together genuine values with the cultural heritage of the different civilizations which have passed through Anatolia over the millennia.

Traditional Turkish handicrafts include; carpet-making, rug-making, sumac, cloth-weaving, writing, tile-making, ceramics and pottery, embroidery, leather manufacture, musical instrument-making, masonry, copper work, basket-making, saddle-making, felt-making, weaving, woodwork, cart-making etc.

Weaving materials in traditional Turkish handicrafts consist of wool, mohair, cotton, bristles and silk. Weaving can be done with all kinds of cloth, and produces plaits, carpets, rugs and felt obtained by spinning thread, connecting the fibers together or by other methods. Weaving is a handicraft which has been practiced in Anatolia for many years and considered as a mean of earning a livelihood.

Embroidery, a unique example of Turkish handicrafts, is not only used for decoration but also as a means of communication tool with the symbolism in its designs. Today, embroidery made with tools such as the crochet needle, needle, shuttle and hairpin designed either as a border or motif, and goes by different names according to the implement used and the technique. These include; needle, crochet needle, shuttle, hairpin, silk cocoon, wool, candle stick, bead and left-over cloth. Embroidery is generally seen in the provinces of Kastamonu, Konya, Elazığ, Bursa, Bitlis, Gaziantep, İzmir, Ankara, Bolu, Kahramanmaraş, Aydın, İçel, Tokat and Kütahya, although it is gradually losing importance and becoming restricted to trousseau chests.

Along with embroidery used in traditional costumes, jewellery is also commonly used as an accessory. All the civilizations which have existed in Anatolia have produced artistic works made from precious or semi-precious stones and metal. Turkoman jewellery is an excellent example of genuine methods that were brought to Anatolia by the Seljuks. In the Ottoman period, jewellery gained importance in parallel to the development of the empire.

In the Bronze Age in Anatolia, bronze obtained by mixing tin with copper, and materials such as copper, gold and silver were also wrought and cast. The most used material is copper. Various techniques, such as casting, scraping, savaklama, küftgani, ajir kesme and kazima were used. There are also different techniques for working other materials such as brass, gold, silver, and today these handicrafts are trying to be kept alive today by using high quality workmanship and a variety of designs. Copper, the commonest metal used today, is still used for kitchen utensils by plating it with tin.

Architecture, whose origins lie in a need to provide permanent shelter, has also changed and adapted in accordance with local environmental conditions. This development led to wood carving gaining its unique characteristics during the Seljuk period. Seljuk woodworking crafts include extraordinary, high-quality workmanship, the commonest products most common being mosque niches, mosque doors and cupboard covers. In the Ottoman period, these techniques were greatly simplified and applied mostly to objects in daily use, such as tripods, wooden stands for quilted turbans, writing sets, drawers, chests, spoons, thrones, rowing boats, low reading desks, Koran covers and architectural works such as windows, wardrobe covers, beams, consoles, ceilings, niche indicating the direction of Mecca, pulpits and coffins.

The materials used in woodworking were mostly walnut, apple, pear, cedar, ebony and rosewood. Wooden objects were created by such techniques such as tapping, painting, relief-engraving, caging, coating and burning, and these are still employed today. The use of walking sticks became popular in the 19th century, and these are still populare and made by the same methods in the provinces of Zonguldak, Bitlis, Gaziantep, Bursa, İstanbul-Beykoz and Ordu provinces. While the handles of walking sticks are made of materials such as silver, gold and bone, the sticks themselves are usually made of rose, cherry, ebony, bamboo and reed.

Making musical instruments has been a tradition for many long years. These are made from materials such as trees, plants and the skin, bones and horns of animals, and are classified into string, percussion and woodwind groups.

Another art form is glazed earthenware tiles, which were brought to Anatolia by the Seljuks. Seljuk artists were especially successful at creating animal designs. The glazed earthenware tiles initiated in the 14th century in İznik, in the 15th century in Kütahya and in the 17th century in Çanakkale, made a posıtıve contributıon and brought new interpretations to Ottoman ceramic and glazed earthenware tile art. Between the 14 and 19th centuries, Turkish glazed earthenware tiles and ceramic art became world famous for their extraordinary creative workmanship.

The most distinctive examples of the glasswork of Anatolian civilizations illuminate the development of the history of glass work. Stained glass in different models and forms was developed by the Seljuks. In the Ottoman Empire, after the conquest of Istanbul, the city became the glasswork centre. Çeşmi-i Bülbül and Beykoz work are examples of techniques that still survive today.

The first production of glass in the form of a bead to ward of the evil eye was carried out by expert craftsmen in the village of Görele in the province of Izmir. It is possible to see beads for warding off the evil eye in every corner of Anatolia. It is believed that the malicious glances aimed at living things or objects can be averted by using these amulets. Amulets made of bead to ward off the evil eye are therefore put in places where everyone can see them easily.

Stonework plays an important role in exterior and interior decoration in traditional architecture. In addition to architecture, gravestones are other examples of stonework. Techniques such as carving, relief and inscription are applied to gravestones. The ornamental motifs used are plants, geometric motifs, writing and figures. Animal figures are less common. Human figures can be found in Seljuk period art.

Basket-making is carried out by weaving reed, willow, and nut branches in a way that has come down from our ancestors. It is now used for home decoration in addition to its original purpose of helping to carry things.

Packsaddles made of felt and rough cloth formed a sub-branch of traditional artwork during the period when saddles were commonly used in rural areas.

As a result of changing living conditions, and particularly industrialization, the production of these has now pretty much ceased altogether.

Embroidery

Embroidery is the ornamentation of materials such as leather, cloth or felt with silk, wool, linen, cotton and metal threads and needles.

The art of Turkish embroidery has a long history. The word “ornament” is used as a definition of decoration in houses, clothes and furnishings. Embroidery began in the palace, later becoming a decorative folk art.

The embroidery techniques and needles that are used today are the end product of many changes based on economic and geographic conditions and aesthetical values.

Turkish embroidery techniques according to the way the needle is used; the needle may applied to the woven threads (Chinese needle, Romanian needle, Cretan needle, French knot, calculation needle, herringbone, eyebrow etc); or to pull the woven threads (scalloped ribbon); needles may help to close the threads (Bukhara knot, Jacobean weft, Maraş work, applique, bead work, sequin work), or to bind the threads (patchwork, dove eye, Antep work, passing work etc.).

Maraş Work (Hole Work)

Motifs of Çorlu Fedelli

Traditional Costume

Female Dress

The traditional clothing for women of Turkey includes the şalvar which is usually worn with upper garments of varying styles and lengths. The traditional şalvar suits are a part of Turkey’s culture back to the Ottoman era. The şalvars are of varying degrees of bagginess and are gathered at the ankle. Bright colours and flowered prints are favoured by rural women. The total female ensemble includes the gömlek (chemise), şalvar and entari (robe).

Village women still largely preserve traditional attire. They wear some locally customary combination of baggy trousers, skirts, and aprons. In many areas it is still possible to identify a woman’s town or village and her marital status by her dress; village women in Turkey have never worn a veil, but they have traditionally covered their heads and mouths with a large scarf. This practice has been revived among the more devout urban women, though the scarf is often combined with Western dress.

Male Dress

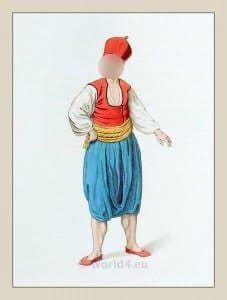

Except in some remote villages, Turkish men today are dressed in the western way. Baggy trousers and colored vests that were worn by Turkish at the ottoman era left room for jeans, pants clip, tight shirts. It is at weddings or traditional festivals that one can see parading the beautiful old traditional costumes. Wide style Sarouel trouser, short jacket, turban and/or Fez, wide belts, thus were dressed the Turks at the ottoman time.

The old caftan

Almost all Arab countries lived under the ottoman umbrella, with the exception of Morocco. The caftan was imported by the Andalusia who left their land to the Maghreb. If the Moroccan caftan has known influences and changes, the ottoman caftan remained monotous. Those Moorish caftans brought from Andalusia were reserved to an elite. Turkish officials, Tunisian or Algerian notables, they were the only ones to wear caftan. So we cannot define it as a component of the traditional ottoman costume.

The saroual, the shirt, the Fez and the Turkish jacket

Under the Ottoman Empire, most of the men were dressed in a traditional garment composed of a waistcoat (“yelek” in turkish), a shirt called “gomlek”, a fez and a sarouel also called salvar (pronounced “chalvar”). Some were wearing a kind of cassok akin to today qamis.

The sarouel and cassok were both decorated by a piece of tissue as a pocket or a belt, called “kusak” pronounced “kouchak”). We can note that at the time, each social class was wearing a different costume according to that if one is close to the Sultan, basic citizen, peasant or scholar.

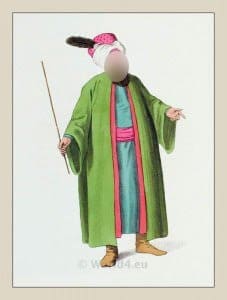

The chief usher to the grand seignior

A greek sailor in the service of the Sultan

Higher administrative official of the Ottoman State

Today we still can see the old Turkish men wearing the wide trouser. They never left anyway their shirt. The embroidered waistcoat in “serge” (a kind of tissue) left room to a western waistcoat of wool.

The inevitable fez

The fez, this red headgear, is part of the traditional turkish costume. It is hat in felt with a rigid and conical shape, dressed by a black tassel screwed above with black strings who are hanging. Also called “Tarbouche” in arabic, it has known a great succes in the different populations of the Ottoman empire.

REFERENCES:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkey

- https://www.goturkeytourism.com/about-turkey/traditional-arts-and-crafts-in-turkey.html

- https://www.ktb.gov.tr/EN-98709/traditional-arts-and-crafts.html#:~:text=Traditional%20Turkish%20handicrafts%20include%3B%20carpet,woodwork%2C%20cart%2Dmaking%20etc.

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Turkey

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/turkish-textiles-history.html#:~:text=Textiles%20like%20cotton%20and%20wool,were%20exported%20the%20world%20over.

- http://www.turkishculture.org/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_salvar#:~:text=The%20traditional%20male%20dress%20includes,of%20Cilicia%2C%20Urfa%20and%20Diyarbakir.

- http://learnturkish.pgeorgalas.gr/DressesSetEn.asp

- https://www.custom-qamis.com/en/blog//the-traditional-costume-of-turkey

- https://www.intoresin.com/blogs/intoresin-guide/the-10-most-popular-diy-crafts-during-covid

Article written by: Arwa Aamir Kalawadwala

M.Sc. in Textile and Fashion Technology

College of Home Science, Nirmala Niketan.

Textile Value Chain Intern.