Tunisian traditional clothing crafts: weaving and embroidering

Tunisians are among the best in the world in creating distinctive signs of their origin. It’s not only the design of a veil or dress for women and jebba for men – it’s the whole image: clothing, make-up, hair-do, shoes, headdress, jewelry, and accessories. To emphasize their identity, Tunisian people need such clothing crafts as weaving and embroidering. Local craftsmen have achieved excellence in making the most exquisite and high-quality clothing. That’s why Tunisians still use the traditional costumes in day-to-day life.

Tunisian people mostly used handmade clothing until the country got its independence in 1956. Since then Tunisian markets were stuffed with imported fabrics and garments. But even today Tunisian traditional clothing crafts – weaving and embroidering – live and thrive. Craft business is rather successful and profitable, which means that Tunisians are able to keep and develop their traditions.

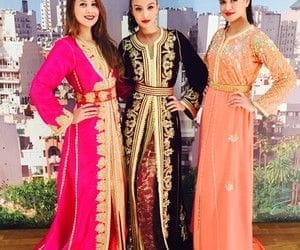

The innovative stream which gives rise to a line of Tunisian Costumes was initiated by ONAT by establishing the “Khomsa d’Or” competition in 1996, giving rise each year to a flurry of creativity (creation of a holding functional city, meeting the requirements of modern life to attend everyday concerns, inspired by traditional Tunisian dress). The craze for this new line of male and female Costumes raises hopes and generates skills.

Weaving and embroidering were among the oldest crafts in Tunisia. And the craftsmen have achieved excellence in making the most exquisite and high-quality clothing. Mainly women were engaged in embroidering and weaving, though, some men also made a living this way. Different regions of the country possess their own techniques, typical patterns, colors, and materials. That’s why it is so interesting to learn about the diversity of Tunisian traditional clothing.

Embroidering in Tunisia

For Tunisian people embroidery is not just a decoration. It never was. They are very serious about it. Today simpler patterns and cheaper threads and fabrics are often used, but even these days, craftswomen compete with each other in embroidering. And 100 years ago every piece of embroidered clothing was a masterpiece. It was like a book, written by the real master of her craft. Every stitch, every outline on cloth had a deep meaning. You could look at the garment and tell what region (sometimes even city or town) is the owner from, is he/she wealthy or poor, married or single, what’s his/her occupation, and many other characteristics.

The patterns and embroidering techniques were passed from generation to generation to keep the art of embroidering alive. Girls were taught to embroider since a very young age. It was obligatory for every woman to have this skill, no matter if she lived in a large city or a small village. Of course, citizens of big cities with huge markets and lots of imported clothes were the first to try international attires instead of local Tunisian clothing after the borders were opened. The ancient customs and traditions were kept much longer in remote villages. But many of Tunisian craftswomen still are specialists of embroidery today. They produce and sell handmade outfits richly embroidered and embellished in traditional style. The most popular are traditional wedding dresses made by these craftswomen. They managed to make such garments look modern but with a touch of a rich past of Tunisia.

Tunisian embroidery uses not only colorful threads but also pearls, sequins, silver plates, crystals, etc. All that makes the clothing look even more festive, expensive, and beautiful. Especially if to talk about the wedding dresses and accessories.

The most famous in the art of embroidering are such cities as Nabeul, Moknine, Rafraf, and the whole Sahel region of Tunisia. Each one of them has its own traditions in embroidering, patterns, threads used by craftswomen, etc. For example, craftsmen in Nabeul prefer floral patterns: flowers, leaves, and similar shapes. Sahelian embroidery in different, with a freer inspiration. Craftsmen leave the whole scenes from real life on the fabric instead of simpler patterns. They work in the style of realism, use patterns with a deep symbolical meaning, and make their garments like an artist makes his paintings. Woolen or cotton dresses with Sahelian embroidery are used by brides on the 7th day of the wedding.

But women are not the only people in Tunisia who use embroidered clothing. Male jackets, jebbas, and other pieces of attire are also embellished with embroidery. Though, they are not as richly embroidered as female garments.

Weaving in Tunisia

The profession of weaving was among the most popular and useful in Tunisia since the late 1950s. People used to make their clothing for the whole family. Women were weaving, sewing, embroidering, and decorating the outfits. Almost every family had all the needed accessories and supplies at home to weave cloth. Today most of the clothing is bought at the markets or in stores; the fabric is woven by machines, but still homemade garments, blankets, and fabrics are in use and are rather expensive. Such male garments as “houli” (a white woolen robe) and “burnous” (a white woolen cloak, often with a hood) are sometimes hand-woven by the wives for their husbands. These pieces of clothing are very elegant, and men take pride in high-quality garments.

Female woven clothing is even more delicate, beautiful, and remarkable. Such women’s pieces of clothing as “houli” (drape gowns) and veils (like mochtiya, bakhnoug, taajira and similar items) are also woven. There is a wide variety of veils and shawls used by Tunisian women. Every region has its typical designs, materials, patterns, and techniques of weaving used to make these items.

Actually, the traditional costumes of Tunisian women differ so much from region to region. And it’s not only the design of a veil or dress – it’s the whole image: clothing, make-up, hair-do, shoes, headdress, and jewelry. Tunisians are among the best in the world in creating distinctive signs of their origin.

The craftswomen mostly weave woolen cloth but they make outfits from cotton and silk as well. Except for clothing, Tunisians also weave blankets and wrap-around cloths. There is a kind of wrap-around skirt, used by both men and women, which is called “fouta”. It is a rectangular piece of stripped fabric. Fouta used to be handwoven once. Though, today this item is mostly produced with a help of machines. Only several craftsmen still make foutas.

At the other hand, the production of handmade and factory produced sefseri (white or beige women’s large kerchiefs that cover most of the body) is experiencing a production boom these days. Sefseries are getting more and more popular in modern Tunisia, so the weaving of this piece is very profitable. As well as making jebbas (traditional male robes).

Tunisian Woman Shawls

1. Women’s shawls

Shawls are textiles that women wear to cover their shoulders. At times, they are very large and can be folded over at the front, forming a sort of cape covering from head to foot.

While the city-based elite in the north of the country have been weaving and wearing shawls of rare beauty, often of silk and in sophisticated colours for some time, the tradition of weaving shawls was more common amongst the Berber population of the mountainous regions to the south of Gabes (Jabaliya), and the Arab population of Sahel, a region north of Sfax including the centres of El Jam and Jebeniana, both of which cultures were less urbanised and used to produce woollen shawls.

With regard to these two cultural groups, despite the difference in ethnic origin, the composition and motifs of the textile designs were very similar, since the Arabs arrived in Tunisia in the 14th century after having spent at least 300 years living alongside the Berbers in Tripolitania, and assimilating many of their customs.

Unfortunately, there is very little information regarding the production and use of Tunisian women’s shawls, as the bibliography is largely sparse. For this reason, to date there has been no suitable appreciation of this article, which in Tunisia more than elsewhere is probably one of the highest expressions of textile tribal art and art in general. We owe much to the work of some dealers (we may mention one name to represent all: Renate Menzel), who with intuition, taste, passion and competence have collected some fine examples and saved these shawls from oblivion, presenting them to the world of collecting in the West and to other dealers and scholars who have explored their beauty and value.

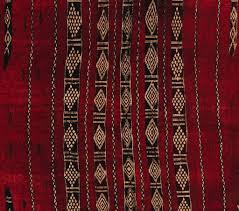

If we examine the various types of Tunisian shawl from closer-to, we find a flat weave worth of attention with regard to tribal weaving in North Africa, not only for their singularity and technical quality, or for their aesthetic value, but above all for their anthropological value, their capacity to reveal and pass on the fundamental rites of passage of the culture that has produced them.

These are not mere clothing accessories, conforming to a reductive interpretation of their social (and euro-centric) importance, but instead something akin to identity documents, through which women declare their age and social status (thanks to the colour), tribe (through the decoration), weaving ability (with the details of the design). For example, in the case of young women of marriageable age, the beauty of their shawls anticipated the degree of prestige of their future marriage, the size of the dowry and so on. We are convinced that in tribal textile art, an object’s narrative capacity is always a fundamental characteristic of its value, and almost always the basis of its technical and aesthetic excellence.

“From an aesthetic point of view, they are highly refined and absolutely contemporary works, closely aligned to the sensibility of many modern artists (…). The extraordinary dramatic nature of the best Tunisian bakhnougs is formed of tiny graffiti of white linen that frame a black or purple field and recalling the graffiti on the rocks of north-west Africa, together with modern photography inspired by genetic codes” (Percorsi d’Africa, edited by Chiara Battini and Arianna Sardella Yeh, Milan 2008).

Sadly, the production of these true works of art has almost stopped, except for a few meritorious crafts cooperatives which, however, have distorted the character of these textiles, making them almost mass-produced and destined for a public formed more of tourists than locals. Tunisian women themselves have almost stopped wearing them. Every tribal culture seems to crumble rapidly upon contact with global information (radio, television, telephone).

“The awareness that in just a few hours or days of travel, it is possible to find everyday objects in large markets is a disincentive to months of work at a loom to make them, and corrodes the ability that would be necessary to continue to weave even those objects intended for special ceremonial occasions” (Chiara Battini, Tribal textiles of northern Africa, paper given at the 2008 Textile Fair of Sartirana). All the more reason, therefore, for the surviving examples to acquire importance from a historic point of view as well.

2. Types of shawl

The women’s shawls that used to be woven in Tunisia have different names according to area of production, size, use for which they were made, and also social status of the person wearing them!

In the Jabaliya area (from the word ‘Jebel’ or mountain), in the south of Tunisia, textiles of extraordinary fineness and beauty called bakhnoug, tajira or keftiya, according to size. These three items, which could be worn together or separately, are the three most important Tunisian women’s shawls of wool. But of these, the bakhnoug is the most typical Tunisian shawl.

The bakhnoug has a rectangular form measuring about one metre by two metres and serving to cover both head and shoulders. It would be woven using white (and very rarely black) wool of high quality and decorated with inserts of cotton or white linen. It could be found in red, dark blue (rarely in black) or left white because, as we have said, the different colours corresponded to the differences in age and social status of the person wearing them. Specifically, young girls would wear white bakhnougs, young women red ones and older women blue (or black) ones.

The shawls were used mainly in winter, but also on the occasion of visits or ceremonies and festivities (weddings, births, circumcisions, etc…); and this both proudly to show the merits of the weaver, and to bring good luck to the events.

The main motifs we find on the highly geometric and abstract bakhnougs are small, simple ones: points, bands, zigzags, diamonds, triangles, snakes, jewels, tattoos, scorpions. And these are similar in every region although their distribution and association within the design vary from district to district. They form an alphabet through which declarations of belonging, of faith and messages of goodwill and hope are expressed, in conformity with a form of magical thinking. The central field may be empty with just a single embroidered motif or adorned with a row of motifs. Normally, all four sides are always embroidered.

In the area of the small town of Matmata, a variant of the bakhnoug used to be made, with a zone of circular red marks and a white edge produced using reserve dye at the two ends of the shawl, which were otherwise usually dark-blue.

The tajira is a rectangular or square shawl measuring between 100 and 110 cm in width and 100 to 150 cm in length, and comes from the southern border region next to Algeria. Usually red or pink (following the introduction of chemical dyes), the lower side has a fringe and the other sides are embroidered with prevalently black and white motifs, except for the top edge which is embroidered with polychrome or band motifs. The embroideries and lower fringe are often of silk. It would be worn on the head to prevent the bakhnoug from being spoiled by the unguents used by the women for their hair.

The motifs that were commonly embroidered differ to those of the bakhnoug because they present animal and anthropomorphic figures: fish, human figures, other animals, palm trees. Like the bakhnoug, so the tajira from Matmata also might have an area with small coloured patches of yellow, orange or red obtained using the reserve dye technique on the side next to the fringe.

The keftiya is the smallest of the shawls and was used to cover the shoulders. It is rectangular and measures about 30 cm in width and 100 cm in length and, like the tajira, served to protect the women’s garments from their hair oil. It is usually red and at the ends has bands of black and white motifs that are very similar to those of the bakhnoug. From an aesthetic point of view, the keftiya is in effect a small bakhnoug, and there is also a delightful variant with circular yellow or orange reserve-dyed patches.

3. Lesser shawls

In the Sahel area, the most common women’s shawl was called mouchtiya or mustiya, and was destined solely for married women. The bride could begin to wear it from the seventh day after her wedding.

The mouchtiya measures 120 cm in width by 240 cm in length and would be worn from head down to the feet, when leaving home, as a sort of long overcoat. It reflects the mainly Arab ethnic composition of the area, which observes the Muslim commands requiring women to cover themselves so that their beauty would remain the exclusive gift of their husbands.

The underlying colour was red, with a highly complex design over the whole surface, formed of black bands with white and red motifs a few centimetres broad alternating with red bands with black motifs, divided by black and white lines. There would be broader areas in the central part decorated with black motifs and white vertical lines. The most common symbols are snakes, zigzags, lanterns, small birds… positioned apparently casually over the field, sometimes in the company of small orange circular patches obtained with reserve dye.

Although at times the weavers are unable to account for the significance of many designs, it is probable that they originally formed part of magical practices and that a given arrangement of symbols was deemed to bring good luck.

Among the minor shawls, finally, it is worth mentioning the ajar and the mendil. The ajar is a type of shawl used by girls in the Jebeniana area and measures about 150 cm in width by 80 cm in length. Generally red (rarely red and black), it has transverse bands decorated with the classic motifs at the ends. The girls of the El Jam region would wear instead a shawl called mendil, which was also red and decorated with small black bands with white motifs on the ends and, sometimes, also in the centre. It would vary considerably in size, from being smaller than an ajar to larger than a mouchtiya.

4. Weaving and colouring

Quite common in various parts of the country until about the 1970s, especially in the rural south and in the border region with Libya, as well as in rural areas in the centre and in the north, women’s shawls were woven on classic vertical looms of the sort most common throughout north Africa. This was true also of silk shawls belonging to the urban elite of the north, which have been left out of this discussion. A more archaic vertical loom using stones to keep the tension in the warps was in use for woollen shawls alone until the end of the 19th century.

Given their importance, the shawls were woven by women using the best sheep’s wool they could find, which would be processed at length to provide long, very slender and tightly twisted yarn. Other yarns used for the decoration were cotton, linen and, more rarely, silk, all produced locally until the end of the 19th century. The decorated portion was made with different techniques: sometimes with supplementary wefts (bakhnoug and ketfyia), sometimes with embroidery (tajira) and sometimes with small areas of reserve dye.

Natural dyes were used for the fabrics derived from plants and insects. This using effective techniques passed down from generation to generation, which the older women would pass down to the younger ones. The natural colours required much time and a lot of work and since not all of the women had the same level of skill, the dyes were sometimes sold to other clans for a high price.

Above all, the final colours were never the same as a previous batch but would have different tones which are often still visible in the shawls, and this suggests that the same colour being prepared for one shawl would be processed in small pots. An important technical feature in the production of the shawls consisted of the fact that the dyeing of the wool in most cases took place after the article was made. Normally, for the production of similar articles in other cultures, the wool used would be first dyed and then woven, using yarns of different colours to obtain the final design.

In the production of Tunisian shawls, instead, the woman works the wool at the loom in its natural colour, alternating it with cotton or natural white linen (using a supplementary weft) or embroidering the cotton or linen once finished. Thus, the difficulty of producing complex and fine designs is considerable. And considerable are the skills of these women who at first sight found it hard to distinguish the different yarns (those of the ground and those of the decoration) and hence the cotton design from the wool ground. And indeed it is said that they would weave by memory and with a light touch!

Once finished, the article would usually be dyed red (the dominant colour) and the parts in white wool took on this colour, while the cotton or lined decoration would remain white, given that these do not absorb these natural colourings easily. In the case of white bakhnougs, a decoration in coloured yard would be woven in, just as coloured silk yarns would be used to embroider the tajira.

We have also seen that there are shawls with small yellow or orange reserve-dyed patches of colour. The women of Matmata would tie small stones or spherical objects into the chosen part of the shawl, which would then be dipped in the dye so that the round forms would appear in that (yellow or orange) colour, surrounded by a border of different colour (where the knot was). This is called tie-dye. The reasons for this practice are unknown to the weavers themselves but in remote times they very probably bore a special magical significance.

Calling them women’s shawls seems all the more appropriate given that in Tunisia, at least as regards the communities mentioned in this article, the weaving and dyeing was the prerogative of women only, unlike in other pre-Saharan zones in which these tasks were undertaken also or only by men. The women rarely left their home. Young wives or unmarried daughters lived at the back of the home (tents or huts), together with the pre-adolescent boys, in the same area in which the family’s animals were kept. The woman’s life was devoted to the family and domestic activities (milling flour, cooking, laundering, looking after the animals, caring for the kitchen garden where present, weaving). The women’s social life was extremely limited, often taking place within a home or outside area at the back, and revolved around weaving. The weaving would be done in a group, with the older teaching the younger.

Once the boys reached puberty, they would be moved out of this area and would work alongside their fathers and take part in his social activities, which were a male prerogative. After marriage daughters would move into their husband’s home. Sooner or later, a woman would find herself pretty much alone in her home, only at times flanked by younger wives (in those Muslim communities practising polygamy), and it was then that she had most time to dedicate to weaving for herself and for her daughters and grandchildren.

Weaving is the only creative activity women are allowed to undertake. We like to think that a mature woman, having survived the hard conditions of her life, finally has a moment for herself, a private time in which to express herself as a human being, aside from her duties to her community. A time to weave freely. And this seems curiously linked to the fact that the finest, most sophisticated bakhnougs are the black or dark blue ones woven by older women.

It is evident, therefore, that Tunisian shawls can be a useful tool for exploring the social and cultural complexity of a community that has almost disappeared, bearing witness to a lost time, a good time, dominated by women.

REFERENCES

Ben Mansour H., Tapis et tissages en Tunisie, Tunis 1999

Benfoughal T., Les costumes feminins de Tunisie, Collection du Musée du Bardo d’Alger, Alger 1983

Coustillac L., “Note sur la teinture vegetale dans le Sud Tunisien”, in Les Cahiers de Tunisie, Nn. 23-24 (1958) pp. 353-363

Flint B., Formes et symboles dans les arts Maghrebins – Tome 2 Tapis-Tissages, Tanger 1974

Gillow J., African textiles, London 2003

Golvin L., Les tissages decores d’ El-Djem et de Djebeniana, Tunis 1949

Reswick I., Traditional textiles of Tunisia and related North African weavings , Los Angeles, 1985

Sethom S. et al., Signes et symboles dans l’ art populaire Tunisien, Tunis 1976

Spring C. & Hudson J., North African Textiles, Washington 1991

Stone C., The Embroideries of North Africa, London 1985

http://nationalclothing.org/africa/43-tunisia/100-tunisian-traditional-clothing-crafts-weaving-and-embroidering.html#:~:text=Men%20wrapped%20in%20traditional%20Tunisian%20woven%20blankets&text=The%20craftswomen%20mostly%20weave%20woolen,which%20is%20called%20%22fouta%22.

By NIDHI SINGH