Tonga, officially named the Kingdom of Tonga, is a Polynesian sovereign state and archipelago comprising 169 islands, of which 36 are inhabited. The total surface area is about 750 square kilometres (290 sq mi) scattered over 700,000 square kilometres (270,000 sq mi) of the southern Pacific Ocean. As of 2016, the state had a population of 100,651 people, of whom 70% reside on the main island of Tongatapu.

Tonga stretches across approximately 800 kilometres (500 mi) in a north–south line. It is surrounded by Fiji and Wallis and Futuna (France) to the northwest, Samoa to the northeast, Niue to the east (which is the nearest foreign territory), Kermadec (part of New Zealand) to the southwest, and New Caledonia (France) and Vanuatu to the farther west. It is about 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) from New Zealand’s North Island.

From 1900 to 1970, Tonga had British protected state status, with the United Kingdom looking after its foreign affairs under a Treaty of Friendship. The country never relinquished its sovereignty to any foreign power. In 2010, Tonga took a decisive step away from its traditional absolute monarchy and towards becoming a fully functioning constitutional monarchy, after legislative reforms paved the way for its first partial representative elections.

|

Kingdom of Tonga |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Nukuʻalofa 21°08′S 175°12′W |

| Official languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2018) |

|

| Religion

(2011) |

List of religions[show] |

| Demonym(s) | Tongan |

|

Independence |

|

| • from protection with Britain (was never colonized) |

4 June 1970 |

|

Area |

|

| • Total | 748 km2 (289 sq mi) (175th) |

| • Water (%) | 4.0 |

|

Population |

|

| • 2016 census | 100,651 (199th) |

| • Density | 139/km2 (360.0/sq mi) (76tha) |

| Currency | Paʻanga (TOP) |

| Time zone | UTC+13 |

CULTURE

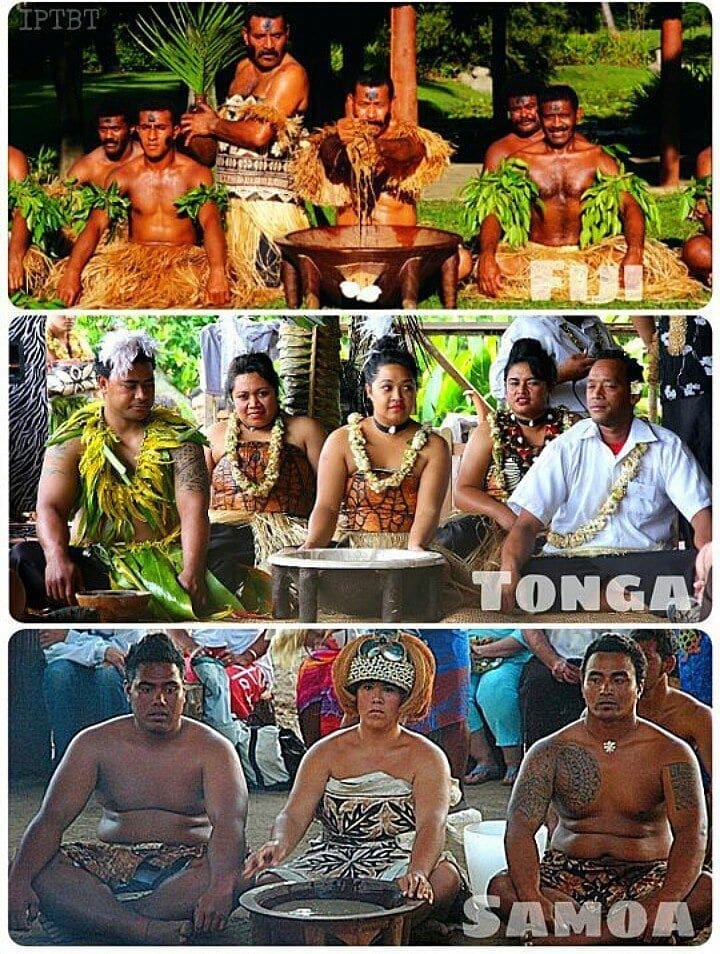

The Tongan archipelago has been inhabited for perhaps 3000 years, since settlement in late Lapita times. The culture of its inhabitants has surely changed greatly over this long time period. Before the arrival of European explorers in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Tongans were in frequent contact with their nearest Oceanic neighbors, Fiji and Samoa. In the 19th century, with the arrival of Western traders and missionaries, Tongan culture changed dramatically. Some old beliefs and habits were thrown away and others adopted. Some accommodations made in the 19th century and early 20th century are now being challenged by changing Western civilization. Hence Tongan culture is far from a unified or monolithic affair, and Tongans themselves may differ strongly as to what it is “Tongan” to do, or not do.

Contemporary Tongans often have strong ties to overseas lands. They may have been migrant workers in New Zealand, or have lived and traveled in New Zealand, Australia, or the United States. Many Tongans now live overseas, in a Tongan diaspora, and send home remittances to family members (often aged) who prefer to remain in Tonga. Tongans themselves often have to operate in two different contexts, which they often call anga fakatonga, the traditional Tongan way, and anga fakapālangi, the Western way. A culturally adept Tongan learns both sets of rules and when to switch between them.

TEXTILE OF TONGA

NGATU

In the Kingdom of Tonga, decorated or painted tapa is called ngatu. This ngatu was originally gifted to Haufangahau College at the annual graduation ceremony in November 2007, when Maureen Khan Hafoka was announced Dux of the College. The tapa, which took four months to make, was made by Maureen’s grandmother and aunties. Gifting of tapa constantly takes place between the Pacific Islands, particularly Tonga and Fiji, and Australia and may return in cycles as the tapa is passed on. Like a lot of Tongan tapa this one is very, very big: five square metres; and was made to be gifted. Tonga makes the biggest tapa or ngatu in the world.

Prince Pilinisi Ngatu is the Tongan word for decorated or painted tapa. This Tongan ngatu is a ngatu tahina. Ngatu tahina is characterised by large areas of light brown paint. This ngatu has no borders on two ends, which is normal, or it may have been cut from a much larger piece as this is sometimes the case when buying or gifting Tongan tapa. Ngatu this size is made in sheets glued together with paste made from arrowroot tubers. The background light brown colour is achieved by a raised stencil or kupesi placed under the cloth, with smaller pieces soaked in dye made from the scraped then squeezed bark of the koka tree (Bischofia javanica) pressed over the ngatu in a repetitive pattern to cover the whole cloth. This process can create an infinite degree of density in the background rubbing to achieve the desired effect. Overpainting was then carried out with deep brown and black paint using a bamboo or pandanus seed spread out like a brush. This ngatu shows the cross-cultural integration of many Tongan tapas. Painted in the contemporary style, it includes western motifs, such as the plane, the lettering “Paul Passenger” in English and Pilinisi Tungi Koe sisi maile o Tungi in Tongan. Tongan tapa often includes historical events from the post-contact era. Perhaps the most used was the Halley’s Comet design (like a sun with a tail) after the comet appeared over Tonga in 1910. The wording Koe sisi maile o Tungi translates as “The festoon or garland (made entirely of the maile plant) of Tungi”. Prince Tungi wore such a garland on certain ceremonial occasions. It is a common image on ngatu, as are other images relating to the Royal family of Tonga. Pilinisi Tungi translates as “Prince Tungi”, the son of Queen Salote, who was most likely the Minister for Aviation c. late 1950s/early 1960s when this ngatu was made. This explains the use of the plane image. Prince Tungi became King in 1965. The Kingdom of Tonga is the only monarchy in the Pacific, which is unique amongst the Pacific nations of Oceania, and Tongans are very proud of this fact.

MAT WEAVING

Mat weaving is one of the ancient Tongan handicrafts. The mats are used for a variety of purposes. Woven mats are commonly used for bedding and flooring. They are also presented at special occasions such as births, deaths, and weddings. Mats are often passed down from generation to generation and historically, they were a symbol of social status. In death, Tongans are wrapped in mats as a sign of respect.

The mats are also worn as a taʻovala, which is a mat worn around the waist. Wearing the ta’ovala is also seen as a sign of respect. It is said that in early times, men returning from a long voyage at sea would cover up with these mats before visiting the chief of the village. Ropes are made out of braided coconut husk are wrapped around the ta’ovala just like a belt, and are another one of the Tongan handicrafts.

Women often wear a modified version called the kiekie. There are many styles and different materials used to make them. Each island group has different materials that they fashion them out of and by looking at the kiekie, it is easy to determine where someone is from, making it a fundamental part of Tongan culture. For example, Ha’apai has very colorful kiekie, which is unique to that island group. Often in Vava’u, the kiekies are decorated with polished coconut shells.

Mats are woven out of pandanus leaves or lo’akau. Different leaves have different colors. Here are the main pandanus leaves used: paongo (brown), tofua (light brown), kie (white), and tapahina (white stripes).

The different species of pandanus leaves are prepared differently. Here is an example of how kie leaves are processed. First, the leaves are boiled to get rid of the outer layer. Next, the leaves are secured to a rope and set in the ocean to soak for days. They are secured by large rocks or cinder blocks. Soaking the pandanus in the ocean allows for the leaves to become bleached and make the leaves softer, therefore, making it easier to work with them when mat weaving. When removed from the seawater, the leaves are rinsed in fresh water and then they are dried in the sun. After the leaves are dry, they can be woven into a mat. Large mats (as big as 20 x 10 feet), can take days to make, but finely woven mats (using a thinner pandanus) can take weeks to make.

CLOTHING OF TONGAN

Tonga has evolved its own version of Western-style clothing, consisting of a long tupenu, or sarong, for women, and a short tupenu for men. Women cover the tupenu with a kofu, or Western-style dress; men top the tupenu either with a T-shirt, a Western casual shirt, or on formal occasions, a dress shirt and a suit coat. Preachers in some Methodist sects still wear long frock coats, a style that has not been current in the West for more than a hundred years. These coats must be tailored locally.

Tongan outfits are often assembled from used Western clothing (for the top) mixed with a length of cloth purchased locally for the tupenu. Used clothing can be found for sale at local markets, or can be purchased overseas and mailed home by relatives.

Some women have learned to sew and own sewing machines (often antique treadle machines). They do simple home-sewing of shirts, kofu, and school uniforms.

Nukuʻalofa, the capital, supports several tailoring shops. They tailor tupenu and suitcoats for Tongan men, and matching tupenu and kofu for Tongan women. The women’s outfits may be decorated with simple blockprint patterns on the hems.

TATTOOING

Tongan males were often heavily tattooed. In Captain Cook’s time only the Tuʻi Tonga (king) was not: because he was too high ranked for anybody to touch him. Later it became the habit that a young Tuʻi Tonga went to Samoa to be tattooed there.

The practice of Tātatau disappeared under heavy missionary disapproval, but was never completely suppressed. It is still very common for men (less so, but still some for women), to be decorated with some small tattoos. Nevertheless, tattoos show one’s strength. Tattoos also tell a story.

BONE CARVING

Carvings are an important part of Tongan craft. This bone carving depicts a whale which is a common theme due to Tonga being an area of whale migration.

REFRENCES

http://www.magsq.com.au/_dbase_upl/education%20sheets.pdf

https://www.livingoceansfoundation.org/ancient-art-of-tonga/

https://geographic.media/oceania/tonga/tonga-photos/tonga-culture-photos/tongan-bone-carving/

By- Janvi Nagada (MSc. in Textile and Fashion Technology)

FLAG

FLAG SEAL

SEAL