New Zealand is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island (Te Ika-a-Māui) and the South Island (Te Waipounamu)—and around 600 smaller islands, covering a total area of 268,021 square kilometres (103,500 sq mi). New Zealand is about 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) east of Australia across the Tasman Sea and 1,000 kilometres (600 mi) south of the islands of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga. The country’s varied topography and sharp mountain peaks, including the Southern Alps, owe much to tectonic uplift and volcanic eruptions. New Zealand’s capital city is Wellington, and its most populous city is Auckland.

Owing to their remoteness, the islands of New Zealand were the last large habitable lands to be settled by humans. Between about 1280 and 1350, Polynesians began to settle in the islands and then developed a distinctive Māori culture. In 1642, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman became the first European to sight New Zealand. In 1840, representatives of the United Kingdom and Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi, which declared British sovereignty over the islands. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire, and in 1907 it became a dominion; it gained full statutory independence in 1947, and the British monarch remained the head of state. Today, the majority of New Zealand’s population of 5 million is of European descent; the indigenous Māori are the largest minority, followed by Asians and Pacific Islanders. Reflecting this, New Zealand’s culture is mainly derived from Māori and early British settlers, with recent broadening arising from increased immigration. The official languages are English, Māori, and New Zealand Sign Language, with English being very dominant.

A developed country, New Zealand ranks highly in international comparisons of national performance, such as quality of life, education, protection of civil liberties, government transparency, and economic freedom. New Zealand underwent major economic changes during the 1980s, which transformed it from a protectionist to a liberalized free-trade economy. The service sector dominates the national economy, followed by the industrial sector, and agriculture; international tourism is a significant source of revenue. Nationally, legislative authority is vested in an elected, unicameral Parliament, while executive political power is exercised by the Cabinet, led by the prime minister, currently Jacinda Ardern. Queen Elizabeth II is the country’s monarch and is represented by a governor-general, currently Dame Patsy Reddy. In addition, New Zealand is organised into 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authorities for local government purposes. The Realm of New Zealand also includes Tokelau (a dependent territory); the Cook Islands and Niue (self-governing states in free association with New Zealand); and the Ross Dependency, which is New Zealand’s territorial claim in Antarctica.

New Zealand is a member of the United Nations, Commonwealth of Nations, ANZUS, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ASEAN Plus Six, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Pacific Community and the Pacific Islands Forum.

| New Zealand Aotearoa (Māori) | |

FLAG

COAT OF ARMS |

|

Location of New Zealand, including outlying islands, its territorial claim in the Antarctic, and Tokelau |

|

| Capital | Wellington 41°18′S 174°47′E |

| Largest city | Auckland |

| Official languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

|

|

| Religion | List of religions

|

| Demonym(s) | New Zealander Kiwi |

| Stages of independence

from the United Kingdom |

|

| • Responsible government | 7 May 1856 |

| • Dominion | 26 September 1907 |

| • Statute of Westminster adopted | 25 November 1947 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 268,021 km2 (103,483 sq mi) (75th) |

| • Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Population | |

| • November 2020 estimate | 5,095,670 |

| • 2018 census | 4,699,755 |

| • Density | 19.0/km2 (49.2/sq mi) (167th) |

| Currency | New Zealand dollar ($) (NZD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

CULTURE

Early Māori adapted the tropically based east Polynesian culture in line with the challenges associated with a larger and more diverse environment, eventually developing their own distinctive culture. Social organisation was largely communal with families (whānau), subtribes (hapū) and tribes (iwi) ruled by a chief (rangatira), whose position was subject to the community’s approval. The British and Irish immigrants brought aspects of their own culture to New Zealand and also influenced Māori culture particularly with the introduction of Christianity. However, Māori still regard their allegiance to tribal groups as a vital part of their identity, and Māori kinship roles resemble those of other Polynesian peoples. More recently, American, Australian, Asian and other European cultures have exerted influence on New Zealand. Non-Māori Polynesian cultures are also apparent, with Pasifika, the world’s largest Polynesian festival, now an annual event in Auckland.

The largely rural life in early New Zealand led to the image of New Zealanders being rugged, industrious problem solvers. Modesty was expected and enforced through the “tall poppy syndrome”, where high achievers received harsh criticism. At the time, New Zealand was not known as an intellectual country. From the early 20th century until the late 1960s, Māori culture was suppressed by the attempted assimilation of Māori into British New Zealanders. In the 1960s, as tertiary education became more available, and cities expanded urban culture began to dominate. However, rural imagery and themes are common in New Zealand’s art, literature and media.

New Zealand’s national symbols are influenced by natural, historical, and Māori sources. The silver fern is an emblem appearing on army insignia and sporting team uniforms. Certain items of popular culture thought to be unique to New Zealand are called “Kiwiana”

TEXTILES OF NEW ZEALAND

MAORI TRADITIONAL TEXTILES

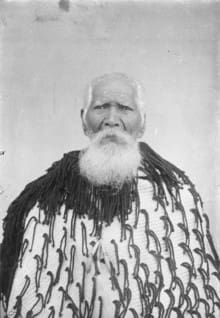

An 1847 portrait of Hone Heke and his wife Hariata wearing cloaks made from Phormium tenax (New Zealand flax) fibre

Māori traditional textiles are the indigenous textiles of the Māori people of New Zealand.

FIBERS AND DYES

Māori made textiles from a number of plants, including harakeke (New Zealand flax), wharariki, tī kōuka, tōī, pingao, kiekie and toetoe—although the paper mulberry was introduced by Māori, who knew it as aute, it seems not to have thrived and bark cloth (tapa) was always rare.

The prepared fibre (muka) of the New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) became the basis of most clothing. The flax leaves were split and woven into mats, ropes and nets but clothing was often made from the fibre within the leaves. The leaves were stripped using a mussel shell, dressed by soaking and pounding with stone pounders, (patu muka), to soften the fibre, spun by rolling the thread against the leg and woven. The fibre within the flax is called muka.

Colours for dyeing muka were sourced from indigenous materials. Paru (mud high in iron salts) provided black, raurekau bark made yellow, and tānekaha bark made a tan colour. The colours were set by rolling the dyed muka in alum (potash).

GARMENTS

There were two main types of garments –

- A knee length kilt-like garment worn around the waist and secured by a belt

- And a rectangular garment worn over the shoulders. This might be a cape-like garment or a long cloak-like garment of finer quality.

Men’s belts were known as tatua and women’s as tu. The man’s belt was usually the more ornate. Belts were usually made of flax but occasionally other materials were used such as kiekie and pingao. Flax belts were often plaited in patterns with black and white stripes. The belts tied with a string tie. Women often wore a belt composed of many strands of plaited fibre.

WEAVING PROCESS

The weaving process (whatu) for clothing was performed not with a loom and shuttle but with the threads being manipulated and tied with fingers. A strong thread is fastened tautly in a horizontal position between two or four upright weaving sticks (turuturu). To this thread (tawhiu) are attached the upper ends of the warp or vertical threads (io). The warp is arranged close together. The weaving process consisted of working in cross-threads from left to right. The closer these threads are together, the tighter the weave, and the finer the garment.

In the case of fine garments four threads are employed in the forming of each aho. The weaver passes two of these threads on either side of the first io or vertical thread, enclosing it. In the continuing the process the two pairs of threads are reversed, those passing behind the first vertical thread would be brought in front of the next one, then behind the next and so on. Each of the down threads would be enclosed between two or four cross-threads every half inch or so.

PAKE/HIEKE

To meet the cold and wet conditions of the New Zealand winter, a rain cloak called pake or hieke was worn. It was made from tags of raw flax or Cordyline partly scraped and set in close rows attached to the muka or plaited fibre base.

A type of garment known as a pake karure was made of two-ply closed strands of hukahuka (twisted or rolled cord or tag) interspersed with occasional black-dyed two-ply open type karure (loosely twisted) muka thread cord. Garments such as these were worn interchangeably either around the waist as a piupiu, or across the shoulder as a cape. These types of garments are thought to pre-date European contact, later becoming a more specialised form during the mid to later nineteenth century, which continues today in the standardised form of the piupiu.

PIUPIU

Piupiu are a kind of grass skirt. The waistband is plaited or in some cases made from tāniko. The body of the piupiu is usually made from flax leaves that are carefully prepared with the muka or flax fibre exposed in some sections to cause geometric patterns to emerge. The unscraped leaves will curl naturally into tubes as the leaves dry, and make a percussion sound when the wearer sways or moves. The geometric patterns can be emphasised through dyeing as the dye will soak more into the exposed fibres rather than the dried raw leaf.

FINE CLOAKS

There were a number of different types of fine cloaks including korowai, kaitaka, kahu huruhuru and kahu kurī, all woven from muka (prepared harakeke fibre) using the tāniko technique.

KOROWAI

Korowai are finely woven cloaks covered with muka tassels (hukahuka). Hukahuka are made by the miro (twist thread) process of dying the muka (flax fibre) and rolling two bundles into a single cord which is then woven into the body of the cloak. There are many different types of korowai that are named depending on the type of hukahuka used as the decoration. Korowai karure have tassels (hukahuka) that appear to be unravelling. Korowai ngore have hukahuka that look like pompoms. Korowai hihima had undyed tassels.

Korowai seem to have been rare at the time of Captain Cook’s first visit to New Zealand because they do not appear in drawings made by his artists. But by 1844, when George French Angas painted historical accounts of early New Zealand, korowai with their black hukahuka had become the most popular style. Hukahuka on fine examples of korowai were often up to thirty centimetres long and when made correctly would move freely with every movement of the wearer. Today, many old korowai have lost their black hukahuka due to the dying process speeding up the deterioration of the muka.

KAITAKA

Kaitaka are cloaks of finely woven muka (Phormium tenax) fibre. Kaitaka are among the more prestigious forms of traditional Maori dress. They are made from muka (flax fibre), which is in turn made from those varieties of Phormium tenax that yield the finest quality fibre characterised by a silk-like texture and rich golden sheen. Kaitaka are usually adorned with broad tāniko borders at the remu (bottom) and narrow tāniko bands along the kauko (sides). The ua (upper border) is plain and undecorated, and the kaupapa (main body) is usually unadorned. There are several sub-categories of kaitaka: parawai, where the aho (wefts) run horizontally; kaitaka paepaeroa, where the aho run vertically; kaitaka aronui or patea, where the aho run horizontally with tāniko bands on the sides and bottom borders; huaki, where the aho run horizontally with taniko bands on the sides and two broad taniko bands, one above the other, on the lower border; and huaki paepaeroa, which has vertical aho with double tāniko bands on the lower border.

KAHU HURUHURU

Fine feather cloaks called kahu huruhuru were made of muka fibre with bird feathers woven in to cover the entire cloak. These feather cloaks became more common during between 1850 and 1900, when cloaks were evolving in their production. Some early examples include kahu kiwi (kiwi feather cloak), which used the soft brown feathers of the kiwi (Apteryx spp). Kahu kiwi were regarded as the most prestigious form of kahu huruhuru. Other kahu huruhuru incorporated the green and white feathers of the kereru (New Zealand pigeon: Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae) and blue feathers from the tui (Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae).

KAHU KURI

A particularly rare type of cloak is the kahu kurī, made from strips of dog skin with hair attached taken from the now extinct kurī (Māori dog), a dog that went extinct around the 1870s.

The main body of the cloak is made up of strips of white-haired dog skin of various lengths, which are sewn onto the kaupapa (main body) of the cloak with fine bone needles to form a tightly woven muka (flax fibre) foundation called pukupuku. The pukupuku weaving technique uses the whatu-aho-patahi (single pair twine) method, which is very similar to the decorative geometric tāniko (fine embroidery or weaving in a geometric pattern) border designs usually seen on the kaitaka (fine flax cloak) class of cloak, and forms a thick and heavy protective garment. The awe (the tassels that fringe the outside length of the cloak) is likely to have been taken from the underside of the dog’s tail. The kurupatu (plaited hem on the cloak edge) is entirely separate to the main kaupapa and made by threading separate strips together to form a length of collar that has been sewn onto the neck of the finished garment.

Kahu kurī are garments possessing great mana (status) and were highly prized heirlooms. Each garment had its own personal name and its history was carefully preserved right up to the time they passed out of Maori ownership. However, most are in museum collections around the world and have lost their provenance. The possession of a kahu kurī immediately identified the owner as a rangatira (chief) or someone who possessed prestige and position within the hapū (family) or iwi (tribe). They were often exchanged between people of rank on important ceremonial occasions and affirmed both the mana of the giver and the recipient. Kahu kurī were made largely between 1500 and 1850, and it is thought that production had ceased altogether by the early nineteenth century.

There are several different varieties of kahu kurī and some tribal variation in the application of the descriptive terms of these types. Some of the types recorded include topuni, ihupuni, awarua, kahuwaero, mahiti, and puahi, but the construction technique remains essentially the same.

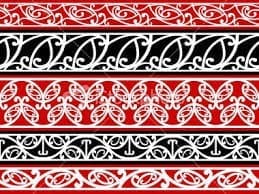

TANIKO

Tāniko (or taaniko) refers to any ornamental border typically found on mats and clothes. Tāniko patterns are very geometric in form because they can be reduced down to small coloured squares repeated on a lattice framework. These base square forms, articulated in the hands of a weaver, constitute the larger diamond and triangle shapes that are visible in all traditional weaving crafts.

Pātiki or pātikitiki (flounder/flat fish: Rhombosolea plebeia) designs are based on the lozenge or diamond shape of the flounder. They can be quite varied within the basic shape.

The kaokao (side or rib) pattern is formed by zigzag lines that create chevrons. These can be horizontal or vertical, open with paces or closed repetitive lines. The design is sometimes interpreted as the arms of warriors caught in haka (fierce rhythmic dance) action.

The niho taniwha (taniwha tooth) pattern is a notched-tooth design found on all types of objects, mats, woven panels, belts, and clothing.

The poutama is a stepped design signifying the growth of man, striving ever upwards.

Tahekeheke (striped) designs refer to any distinct vertical patterning.

The whetū (stars), purapura whetū (weaving pattern of stars) or roimata (teardrop) pattern is a geometric design using two colours and alternating between them at every stitch. This design is associated with the survival of an iwi (tribe), hapū (sub-tribe), or whānau (extended family), the idea being that it is vital to have a large whanau, just as there are many stars in the Milky Way.

KOWHAIWHAI

Kōwhaiwhai are traditional Māori painted scroll patterns. Kōwhaiwhai are mainly used for decorative purposes, so you often see kōwhaiwhai designs adorning the ridgepole and rafters of wharenui – meeing houses. When used in this way kōwhaiwhai depict tribal lineage, capture memories, and tell stories.

There are different stories about the origins of kōwhaiwhai across the different iwi and hapū of Aotearoa. Some attribute the origins of kōwhaiwhai to rock art, others place the origins with whakairo – carving and other information tells us oldest known examples of kōwhaiwhai patterns are on hoe – paddles held in different museum collections around the world.

Kōwhaiwhai designs involve a fair amount of mathematical precision, they use symmetry, rotation and reflection. The most basic design element in kōwhaiwhai is the koru or pītau, and the kape – crescent. The design process elaborates on these motifs to produce the scroll patterns.

Colours used in kōwhaiwhai are traditonally red, black and white. These were made using natural pigments like iron-rich powdered stone for red, charcoal for black, and white clay for white, mixed with shark oil to produce the paint. Kōwhaiwhai in contemporary art makes use of many other colours and materials.

CLOTHING OF NEW ZEALANDERS

WOMEN

1840s to 1890s

In the 19th century women’s fashion in New Zealand took its lead from London and Paris. Fashion extracts from British periodicals were reprinted in New Zealand newspapers from the early 1840s. Fashion was largely an elite concern, revolving around dressmakers, milliners, mantlemakers (who made cloaks) and stay and corset makers.

In the 1850s and 1860s domestic sewing machines and paper patterns became available, making home dressmaking easier and giving more women the chance to be fashionable.

NIGHT ATTIRE

Considerable skill was needed to accurately cut, piece and fit a woman’s dress and style a hat or a corset to match. Women’s dresses had tight bodices and full-length skirts, and were often trimmed with ruching or fringing. Skirts were supported by dome-shaped crinolines (flexible metal cages underneath) in the mid-19th century and bustles (pads worn at the back) in the late 19th century. Corsets gave shape to the waist.

The health effects of restrictive women’s clothing were debated in the late 19th century. Feminists advocated ‘rational’ dress (a jacket, blouse and knickerbockers) instead of a corset and long skirt. From the 1890s women’s increased participation in sports, such as cycling, encouraged lighter, looser styles that allowed freedom of movement. Tailor-made serge jackets and skirts, worn with a blouse, were a new form of daywear.

SWADDLING WOMEN

Some 19th-century feminists linked women’s clothes with oppression. Alice Burns wrote that they were ‘the swaddling clothes of a sex that has not yet asserted its right to perfect freedom.’ Swaddling clothes were strips of cloth wrapped around a young baby’s body to restrict its movement.

1900s to 1940s

The first decade of the 20th century was a decade of unabashed femininity in women’s fashion. Machine- and hand-made lace was used in abundance. Oversized hats, often adorned with ostrich feathers, were a striking feature. Some women went without corsets.

From the First World War necklines were cut lower and skirts became shorter. In the 1920s women’s clothing was noticeably simpler, looser and less restrictive. Tubular, low-waisted dresses were worn at mid-calf or knee length, making footwear more visible. Brassieres and girdles replaced corsets. Close-fitting cloche hats were worn, and gloves remained important on formal occasions.

In the 1930s waistlines returned to their usual position. Dresses with bias-cut draped skirts were fashionable, as were fox furs. Suits were a staple feature of women’s wardrobes. Some women wore shorts and trousers for outdoor recreation such as tramping, but most sports were played in skirts.

During the Second World War new clothing was rationed. Economies were made; jackets and skirts were often left unlined. Emphasis was placed on styles that were serviceable and elegant. Tailored jackets were worn with blouses and knee-length skirts. Hats and gloves remained necessities. Immediately after the war French fashion designer Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’ offered a more feminine aesthetic, with a nipped-in waist and longer, fuller skirts. Shoes had a moderately high heel and were tapered at the front.

1950s to 2000s

In the 1950s trousers became more common for women. Women’s trousers were tapered, and came in a variety of tartan, checked and striped fabrics. They were worn with colourful sweaters. Strapless evening dresses and swimsuits were now available. Conservative dressers wore twinsets (a matching woollen jumper and cardigan) with pleated skirts.

Synthetic fabrics were much more widely used in the 1960s. They could be permanently pleated and did not need ironing. Many garments were stiffly structured, with bold detailing, such as top-stitching and large buttons. Hemlines shot up above the knee, culminating in the miniskirt and mini-shift. Pantyhose replaced stockings and suspenders. Towering platform-heeled shoes were fashionable later that decade and into the next.

In the 1970s hippies went back to nature, wearing flowing dresses of cotton muslin with pintucks, lace and braid. Paisley and floral motifs were popular. Unisex styles, such as jeans and T-shirts, became more prevalent. Some feminists shunned fashion by wearing dungarees. Hat-wearing was now uncommon.

By the 1980s many more women were in the paid workforce than previously. Some adopted a corporate style of brightly coloured suits with big shoulder pads, while others opted for casual sportswear, including running shoes. Trousers were full at the waist and tapered at the ankle. In the late 1980s import restrictions were lifted, prompting a wave of clothing factory closures as imported garments became available.

The New Zealand fashion design industry assumed more importance from the 1990s. In the mid-20th century New Zealand had few recognised fashion designers, a large, professional garment industry and many home sewers, but in the 2000s this situation was completely reversed.

MEN

Men’s clothing has been characterised by the use of sturdy fabrics, a restricted palette of black, blue, brown, white and grey, and standardised tailoring techniques. Changes in men’s clothing have been more subtle than those in women’s clothing.

Men – particularly those with white-collar occupations – have always shopped for clothing, fashionable or otherwise, and paid attention to their appearance. This contradicts the common belief that fashion, and indeed clothing in general, has not been a male concern.

1840s to 1890s

Mid-19th-century men’s clothing was based on four main garments: shirts, waistcoats, trousers and coats.

As early as 1840 there were men in New Zealand who took fashion and appearance seriously. Tailors’ advertisements quoting knowledge of up-to-date European styles indicate that fashion was used as a selling point. Yet writing about Wellington 10 years later a lack of ‘smartness’ was noted by one author. Frock coats and top hats were largely restricted to men in business and professional occupations.

1900s to 1940s

In the 20th century the most enduring form of men’s clothing was the suit, which underwent major and minor variations in fabric and style. In the first decades morning suits, frock coats and lounge suits were the main types of suits. Detachable collars, neckwear such as ties or cravats, tie pins or clips, watches and watch chains, studs, gloves and sticks were important dress accessories, along with hats and shoes.

Suit wearing became less prescriptive as the century progressed. When judged against British standards in the 1930s, New Zealand men were described as ‘not, in the main, conventional folk in the matter of attire’. Visiting royalty could provoke feelings of self-consciousness about what to wear. Few events beyond weddings and funerals called for the wearing of ‘correct’ clothing.

Dressing in a well-cut and up-to-date suit was not financially possible for countless men; neither was it necessary for those in many walks of life, such as farmers and labourers. A ‘best suit’ for church, town and other special occasions was all that was required. This could be a significant investment for a young man, and many suits aged with their wearers. Sports jackets and trousers had long-standing popularity.

SUIT-SKIN

There were major differences between the clothing of blue-collar and white-collar workers. Labourers wore cloth caps, open-necked or collarless shirts, with or without waistcoats, woollen trousers (usually with belts, not braces, by this time) and heavy boots. Sleeves were commonly rolled up. Overalls were more widely worn for work by the mid-20th century.

1950s to 2000s

Jeans were derived from working men’s clothing, and were first worn by young men as a distinctive youth style in the 1950s. Since then they have been available in many styles – flared or straight, tight or baggy, patched or studded, pristine or stained, belted or braced, slung high or low – and are typically worn with T-shirts. Both items are now worn universally. Almost all men wore hats when out in public until the 1960s.

FASHION FANCIER

Visitors to Eden Hore’s Glenshee farm in Central Otago can see a remarkable collection of 1970s New Zealand women’s clothes, with over 200 examples of what Hore called ‘high and exotic fashion’ on display. Hore preferred flamboyance in the garments he collected. All were intended as one-off pieces by designers such as Vinka Lucas, Maritza Tschepp, Kevin Berkhan and Colin Cole.

Suits made from synthetic fabrics, such as crimplene (made of terylene), became widely available in the 1970s. Menswear in this decade included a wider colour range, particularly browns, oranges and mustards, and wide shirt collars, ties, lapels and trouser cuffs. More casual work clothing, including short-sleeved shirts and walk shorts, was emerging, and few men were wearing three-piece suits and hats. A basic suit, shirt and tie remained standard business and formal wear though.

That fashion has a following with men in New Zealand in the 2000s is confirmed by the emergence of men’s fashion magazines such as FQ Men (2004–7) and menswear collections at New Zealand Fashion Week.

CHILDREN

New Zealand children are said to have dressed with more freedom and informality than their British counterparts, a characteristic shared with Australian children. Children often went barefoot, regardless of their parents’ financial status. Despite such steps towards the loosening of old-world conventions, not all children dressed alike – what they wore was influenced by their gender, age, social class, ethnicity, locality and upbringing. Children had little choice in what they wore, especially if resources were limited.

MILESTONES

Many of the key milestones of childhood involve steps towards wearing adult styles of clothing. Set practices, such as breeching boys at the end of infancy (when they began wearing trousers instead of gowns) and putting girls’ hair up at the end of adolescence, once signalled increasing maturity. In the 20th century, as childhood became more prolonged, such clearly defined stages were not so evident.

19th CENTURY

Colonial children’s garments became increasingly gendered as they aged. Male and female babies were dressed in the same manner. Many layers of garments were used to provide warmth, including underclothing, gowns, shawls and caps. As the century progressed, robes became shorter, reaching to just below the feet. Long robes were only retained for christenings. Boys moved into knickerbocker suits, and girls continued to wear dresses, which by the late 19th century were often yoked and frilled, with a washable cotton pinafore over the top for cleanliness.

LABOUR OF LOVE

Keeping up children’s appearances was a significant amount of work for mothers. It was one of the ways in which ‘motherhood’ was on display. A Plunket nurse noted in 1912 that ‘mothers make themselves extra work by putting white starched gowns on the baby instead of just making a plain silk gown which can be washed and done up at a moment’s notice, making the baby look just as nice.’

20th CENTURY

New forms of playwear, such as romper suits (a loose-fitting one-piece garment with buttoned or elasticised pants) were available for young children in the early 20th century. Many variations on playwear developed. Staple items for boys through the mid-20th century were shorts and shirts. Girls wore dresses, or shorts or rompers with blouses. Jumpsuits were popular in the 1960s and 1970s, signalling a wider social acceptance of girls in pants, followed by denim dungarees in the 1980s and 1990s.

KNITWEAR

The popularity of homemade knitwear was a significant development in children’s clothing in the 20th century. Jerseys and cardigans became widespread forms of children’s wear, until they were superseded by sweatshirts in the late 20th century.

Knitted fabrics were more widely used after the Second World War, and in the 2000s there were very few children’s garments for which these were not used. Most casual children’s wear – hoodies, T-shirts, track pants, tunic dresses, skirts and leggings – was made from cotton and polyester knits.

Significantly less clothing was made for children at home. Gendering of children’s clothing had become less consistent. Boys’ and girls’ clothing could range from unisex to unashamedly gendered styles, with pink predominating in the wardrobes of many young girls.

FORMAL CLOTHES

Dressing up for formal occasions, such as weddings, has been a long-standing feature of childhood. At these events children’s clothing was more likely to resemble adult clothing. It was newer, fancier, cleaner, and, if not starched, then more crisply pressed than everyday clothing. Special accessories, including jewellery, were often worn or held. Wearing ‘Sunday best’ was a weekly routine for children of church-going parents.

DRESSING UP

Fancy-dress balls were a prevalent feature of childhood from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. These began as fundraisers for such causes as children’s hospital wards, or for special occasions such as the Queen’s Birthday. In the late 19th century children’s costume choices came largely from European art, history, literature and popular culture. Military and humanitarian archetypes such as ‘rough rider’ and ‘Red Cross nurse’, and racial stereotypes such as African Americans or ‘Māori maidens’, became common in the early 20th century.

For many decades through the mid-20th century games of cowboys and Indians were common. They derived from a long tradition of the Wild West as popular entertainment. Cowgirls also dressed for a part in the skirmishes that eventuated.

In the 2000s dressing up in character continued to be popular, particularly for birthday parties and school fun days. Mass-market dressing-up costumes, such as Superman and Disney Princess outfits, co-existed with creations inspired by wearable art and arts recycling movements.

CLOTHING AND IDENTITY

Clothing is one of the most immediate ways of communicating identity. European clothing is the dominant mode in New Zealand, as in many other parts of the world.

A national dress?

New Zealand does not have a specific national dress. Customary Māori clothing is the only form of dress that is distinctive to New Zealand. Kahu (cloaks) give significant mana and honour to official occasions, such as royal tours and state funerals.

In Europe, national dress evolved from peasant or folk styles and was linked with nationalist movements. Many of these forms of dress, most notably the Scottish kilt, were brought to New Zealand by migrants.

Subtle details mark out Pākehā New Zealanders travelling overseas. In the 19th century these included a piece of pounamu (greenstone) on a man’s watch-chain. The 21st-century equivalent was a pounamu pendant.

CROSS-CULTURAL CLOTHING

With European settlement Māori men and women – especially those living near mission stations and town settlements – began wearing European clothing. One-way Māori obtained European clothing was as payment in land transactions. Māori men and women wore European clothing in a variety of ways and on their own terms. Many outfits blended Māori and European styles.

Māori design has had an impact on European clothing in New Zealand. A widely used motif is the spiral koru, a form based on the unfurling fern frond that represents new life.

Pacific clothing influences have also been apparent. Since the 1970s Pākehā New Zealanders have sometimes worn colourful Samoan ie lavalava (a wrap-around length of printed fabric) to the beach.

In the 20th century distinctive national and ethnic clothing was usually only worn for special occasions, such as weddings and funerals, and national and religious days. With the dramatic increase in ethnic diversity in New Zealand a greater variety of everyday clothing today is non-European.

CLASS DISTINCTIONS

Colonists dressed differently depending on their class. An 1849 handbook for intending immigrants emphasised plain, hard-wearing flannel, cotton, worsted and fustian garments for labouring men. Gentlemen, on the other hand, were advised to bring 72 dress shirts and 40 waistcoats.

Women who dressed above or beneath their station according to old-world values were treated with either tolerance or disapproval, depending on the observer’s attitude. The cleanliness or dirtiness of clothing was also commented upon. Tensions could occur in relations between servants and mistresses over matters of dress.

Into the 20th century class differences continued to be apparent in clothing. People were categorised as ‘vulgar’ or ‘cultured’ on the basis of personal appearance. Well-off people could have bespoke clothing made for them by dressmakers and tailors.

People in more modest circumstances made their own clothes. Those living in poverty needed to find ways to make ends meet, particularly when unemployment rates were high. Sewing skills were crucial. The charitable and commercial trade in second-hand clothing was significant. Unwanted clothing and textiles were circulated within families and communities.

OTHER IDENTITIES

Gays and lesbians

In the era when sex between men was illegal, homosexual men wore clothing that was only subtly different to that of their heterosexual counterparts, but that still allowed them to recognise one another. Some were meticulous in their attention to clothing; others demonstrated a flair for colour or style. Hairstyles, such as a peak at the nape of the neck, and jewellery, such as pinkie rings, could signal belonging. Homosexual law reform in 1986 allowed gay men to display their sexuality more openly – some chose to do this by dressing flamboyantly.

Lesbians also signalled their sexual identity through appearance, with a number choosing short, spiky haircuts, trousers and flat shoes. Some activist lesbians wore T-shirts or badges with lesbian slogans. From the 1990s ‘lipstick lesbians’ donned more traditionally feminine clothing.

JEWELRY OF NEW ZEALND

MAORI KORU JEWELRY

One of the most popular shapes found in Maori jewelry is the Koru, also referred to as Hei Koru (Hei translates to suspend, as in wearing a necklace). The Maori carve beautiful necklaces, pendants, rings, and earrings out of bone and jade (greenstone) in this shape. Koru Jewelry is for sale in many areas of New Zealand and on many online stores. This jewelry makes great gifts for women and for men. The Koru symbol can be found throughout New Zealand. The design is found in paintings, sculptures, tattoos (moko), jewelry, and even as the logo for Air New Zealand. On this page are a list of facts about Hei Koru; including the meanings the Maori attach to this shape, where you can buy Koru jewelry (and other Maori jewelry), and the importance of the silver fern to the people of New Zealand.

MAORI HEI MATATU JEWELRY

Hei Matau is a Maori carving design that is in the shape of a fish hook. The Maori make beautiful necklaces, pendants, and other types of jewelry with this design.

Why the Hei Matau is an Important Symbol to the Maori

As mentioned above fishing was very important to the Maori. The Maori regarded fishing as tapu (a sacred activity) and there were rules dictating when they could fish and how fishing nets should be made. The fishermen would release the first fish they caught to please the god of the sea, Tangaroa. They also tried to please Tangaroa through prayer, rituals and talismans such as the Hei Matau which they hoped would protect them on fishing voyages.

Bone

Whale bone has traditionally been the main material the Maori used to carve fish hooks. The Maori also used bone from other animals such as cattle, birds, and dogs. Modern day laws put in place to prevent whale hunting have made whale bones scarce and therefore cattle bone is usually used instead. Pieces made of whale bone are highly valued. Maori carvers can still obtain whale bone from beached whales. In New Zealand the Maori have legal rights to the bones of beached whales.

Greenstone (Jade)

Hei Matau Carvings made from greenstone (New Zealand nephrite jade) are even more valued than whale bone for the Maori. Greenstone has spiritual significance for the Maori and is a highly-valued material. This jade is extremely hard and the fact that the ancient Maori craftsman could carve it into beautiful works of art is an amazing accomplishment. The Maori valued greenstone so highly that items made from this material were often passed down from generation to generation.

TATOO- TA MOKO

Tā moko is the name for Māori tattooing and its associated tikanga/practices. Traditional tā moko used uhi – a traditional bone chisel with a mixture of natural dye. Over time, the bone uhi was replaced with a needle uhi and finally a tattoo gun and ink. In recent times some Kaitā (tā moko practitioners) have revived the use of the bone uhi.

Kirituhi is another form of tā moko. It is a Māori style tattoo either made by a non-Māori tattooer, or made for a non-Māori wearer. Kirituhi has mana/authority and/or prestige of its own and is a design telling the unique story of the wearer in the visual language of Māori art and design. Kiri means ‘skin’, and tuhi means ‘to write, draw, record, adorn or decorate with painting’.

The origins of moko comes from the story of Niwareka and Mataora who travelled into the underworld bringing back weaving which is associated with Niwareka and tā moko which is associated with Mataora.

CARVING- WHAKAIRO

There are three main forms of Māori carving using either wood, bone or pounamu.

Intricate wood carvings can be found on meeting houses and marae throughout the country, created by (tohunga whakairo) master carvers. The carvings tell each tribe’s story and tales of important historical ancestors and events. Wood carving is also used to create waka (canoes), certain weapons and musical instruments.

Bone carving (traditionally from whale bone, but nowadays from beef bone) is another important art form. Bone carvings are mainly used for jewellery and specific shapes are used to symbolise certain things and many of the same shapes are used in the carving of pounamu (New Zealand jade)

REFRENCES

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand#Culture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C4%81ori_traditional_textiles#:~:text=M%C4%81ori%20made%20textiles%20from%20a,(tapa)%20was%20always%20rare.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/clothes/page-5

http://maorisource.com/Maori-Koru-Jewelry.html#:~:text=Open%2FClose%20Menu%20One%20of,(greenstone)%20in%20this%20shape.

By- Janvi Nagada (MSc. in Textile and Fashion Technology)