INTRODUCTION TO TEXTILES OF IRAN

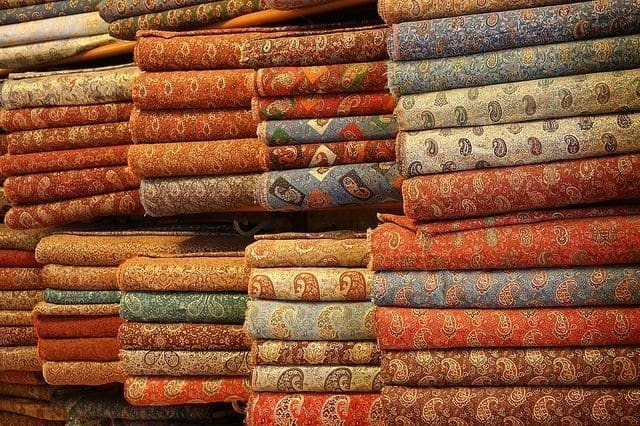

Iran has a rich textile history. Archeologists can date the country’s textile production back at least 6,500 years. In those early years Persia produced tapestries and carpets for domestic and international markets, which were particularly renowned for their elaborate designs and colors. To this day, Persian carpets are still considered among the most beautiful and well-crafted in the world; many are also regarded as artistic works and showcased in museums and private collections.

Not only is the textile industry an important part of Iranian history and culture, it also plays a key role in the country’s economy. Iran is the 36th biggest exporter of textile products in the world. Today, the industry represents 13 percent of all industrial jobs in Iran, most of them concentrated in carpet production.

Iranian companies produce a range of textile products, including carpets, blankets, knitwear and fabrics, using processes such as dyeing, weaving, spinning and printing. Most fabrics are made with domestically produced cotton, although in recent years an increasing amount of cotton is being imported. This low cost of ingredient sourcing provides the country a comparative advantage in textile production. Another advantage for the industry is low labor costs. A study published in 2011 in the Iranian Economic Review found that worker pay in the textile industry was more than 7 percent lower than the average wage for other industries. In part due to these benefits, as well as the strong appetite for Iranian carpets around the world, Iran is a major carpet producer and exporter, making over $300 million from exports in 2015.

The industry, however, is not without challenges. Ageing machinery and a dependence on the import of foreign machines and technology caused the industry to suffer throughout the twentieth century. The country also saw a significant drop in foreign investment after the Iranian revolution. Since then, sanctions have had a significant impact on the Iranian textile industry – particularly after President Bill Clinton restricted all trade with the country in 1997 and again years later when President Barack Obama restricted trade via sanctions, including ban on carpets of Iranian origin from entering the U.S. As a result, sales and employment in that sector decreased.

Naqsh Embroidery (Iran)

Fragment of Naqsh embroidery from Iran, 19th century.Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, acc. no. T.61-1933.

Naqsh work is one of the most famous and striking forms of Iranian embroidery, and was popular in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is characterised by its diagonal bands and patterns of very densely worked stitching. The embroidery was especially used for panels that were sewn onto garments, in particular the lower legs of women’s voluminous trousers.

The diagonal bands include smaller stylised motifs, often of flowers, birds, or vases. Because of the intricate and dense nature of the embroidery, the panels were rigid, and hence also long-lasting. They were consequently often removed when the rest of the garment was worn out, and sewn onto a new garment.

The panels were either wool on wool or silk on wool. Sometimes the ground material is cotton. At times metal thread was used. In later years the diagonal patterns were reproduced in printed fabrics that were worn in particular by the Zoroastrian community Iran.

Panel of Naqsh embroidery, Iran

Fragment of embroidered fabric in the Naqsh tradition, perhaps for a pair of woman’s trousers. Iran, (early) 19th century.Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. no. 2016.1307.

The collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio, includes a piece of fabric that was probably meant for a pair of woman’s trousers. The fragment measures 65 x 51 cm and is made of a cotton ground material with silk thread embroidery in outline stitch. The embroidery consists of diagonal bands in the Naqsh tradition.

Prayer Mat (Iran)

Qajar-period, Iranian prayer mat.Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, acc. no. 15-1877.

The collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London includes an Iranian, Qajar-period prayer mat. The mat measures 130 x 90 cm. The quilted mat has a yellow upper layer that is made of silk and cotton satin. It is decorated with silk thread using straight and running stitch (or back stitch?) and couching. The mat is padded and quilted with a cotton lining. The mat has a woven silk facing (edging).

The mat has the main design of an arch (recalling the mihrab), typical of a prayer mat or cloth. Inside the arch there is a roundel, which denotes its use by a Shi’ite Muslim. It is used to indicate the place for the small piece of earth from the holy Shi’ite site of Kerbela (now in Iraq), which is touched by the man or woman when carrying out the required prostations.

Qajar-era floor covering, Iran

Qajar-era embroidered floor covering from Iran, 19th century.Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. no. 1916.1313.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, houses a Qajar-era (nineteenth century) floor covering from Iran, with silk thread embroidery on a cotton ground material. It measures 175 x 118 cm. The embroidery shows a large stylised representation of a lion in the centre, surrounded by various repeated hunting scenes, including a horseman with a bird of prey, a lion attacking a bull, and nightingales.

Qajar-Era Tent Panel from Iran

Qajar-period tent panel, Iran, decorated in the so-called Rasht style.Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, acc. no. 858-1892.

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London houses a fragment of a tent panel from Qajar-period Iran. It is decorated partly in the typical Rasht-style (Rashti-duzi), named after an Iranian town north of the Elburz mountains close to the Caspian Sea. The panel is made of felted wool, embroidered with silk and metal thread and inlay patchwork (the latter being typical for Rasht work).

The embroidery is mainly carried out with chain stitch and, to a lesser degree, with straight stitch. The metal threads are couched. The fragment measures 69 x 43 cm. The panel can be compared with the complete Qajar-era tent now in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art (2014.388).

Rasht-style prayer rug from Iran

Prayer rug from Iran, Rasht-style inlay work, 19th century.Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. no. 1916.1297.

The Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio, houses an Iranian prayer rug with inlay patchwork in the Rasht tradition. It measures 195 x 133 cm and is made of wool and woollen inlays, with silk thread embroidery worked in chain stitch. A large representation of a cypress tree occupies the centre of the rug, placed on top of peacocks and dragon heads.

Inlay patchwork is typical for the traditional decorative technique of Rasht, in northern Iran. Compare the Qajar-era tent panel now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (acc. no. 858-1892), and the royal tent of Muhammad Shah Qajar, also in the Cleveland Museum of Art (acc. no. 2014.388).

Royal Tent of Muhammad Shah of Iran

Royal tent of Muhammad Shah, Qajar-dynasty king of Iran from 1834-1848.Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. no. 2014.388.

The Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio, holds in its collection a ceremonial tent that is inscribed with the name of Muhammad Shah, the Qajar dynasty ruler of Iran between 1834 and 1848. The tent measures 360 x 400 cm, and the side panels reach to a height of 165 cm.

The inside panels are made of (felted?) wool with inlay patchwork (also wool) and silk thread embroidery worked in chain stitch. The outside is made of cotton and wool. Inlay work is typical for the traditional decorative technique of Rasht, in northern Iran. Compare the Qajar-era tent panel now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (acc. no. 858-1892).

Interior of the Qajar-era royal tent now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. no. 2014.388.

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES OF IRAN

Although the majority of Iranians are Persian, Iran has a varied population that includes different ethnic groups, each with their own language, tradition, and clothes, all of which add to the richness of the country’s culture. Traditionally marked in women’s clothes, it’s easy to identify which region or tribe the person belongs to based on the colorful fabrics, embroidered patterns, decorative jewelry, and style of hijab. Here, we uncover the traditional dress of Iran’s diverse people.

Bakhtiari

The clothes of the Bakhtiari nomadic tribe are rather versatile, accounting for the extreme weather conditions they may encounter during migration. Men wear tunics, wide trousers fastened at the ankle, and wool skullcaps. Colorful, layered skirts paired with matching vests are common for women. Their long scarves are embellished with hand-stitched designs or ornaments.

A Bakhtiari family © Ninara / Flickr

Qashqai

Of Turkic origin, the Qashqai are another nomadic tribe. Women are distinguished by their voluminous, multi-layered, colorful skirts and long headscarves pinned under the chin, which allow loose pieces of hair to frame their face. Men’s round hats are made of sheep hair, which is unique to this tribe.

Qashqai woman © Ninara / Flickr

Baluchi

The southeastern Sistan and Baluchestan province borders Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the traditional clothes of this region therefore resemble the typical shalwar kameez of these neighboring countries. Along with pants and colorful embroidered knee-length dresses, women adorn themselves with gold bracelets, necklaces, and brooches, and a second, longer shawl often covers their head and shoulders. Long pants, loose-fitting shirts, and a turban are customary for men.

Turkmen

Earthy tones dominate the traditional dress of Turkmen men and women. Wearing long dresses with open robes, women often conceal part of their face with a cloth hanging just below the nose. Wool hats, worn to protect against cold weather, are the prominent feature of men’s garments.

Kurds

Kurds have varying styles, as reflected by their residence in different regions. Both men and women tend to wear baggy clothes shaped at the waist by a wide belt. Men wear matching jackets, and women decorate their headscarves with dangling coins and jewels.

Kurdish women in traditional clothes © Hannahannah / Wikimedia Commons

Lur

In contrast to Lur men, who favor neutral colors in their baggy clothes, women lean towards bright, feminine colors, with the trademark stripes hemmed on the pant cuffs. A vest reveals the sleeves of the long dress worn over the pants. After wrapping the headscarf around the head, neck, and shoulders, a long piece is left hanging down the back.

Traditional clothes of Lur women © Shadegan / Wikimedia Commons

Gilaki

Worn with long shirts and matching vests, floor-sweeping skirts with colorful horizontal stripes at the bottom are the discerning feature of the traditional Gilak wardrobe in the northern Gilan province. Men are distinguished by the wide cotton belt around the waist.

Tourists try traditional GIlaki clothes © Ninara / Flickr

Mazandarani

With pants worn underneath, the traditional skirts of the northern Mazandaran region are known to be much shorter and puffier than in other regions. Cotton shirts and hunting trousers with the socks and/or boots worn just below the knee are typical for men.

Abyaneh

In the village of Abyaneh, the aging population has maintained their traditional clothes. Women continue to don airy, below-the-knee skirts and their signature long, white floral scarves that cover the shoulders. Traditional men dress in wide-legged black pants, colorful vests, and wool skullcaps.

Long, floral scarves typical of the village of Abyaneh © Ensie & Matthias/ Flickr

Bandar Abbas and Qeshm

The women in the southern port town of Bandar Abbas and the island of Qeshm are notable for their brightly colored, floral chadors and niqâb, which come in two types. The first gives the impression of thick eyebrows and a mustache from afar, a ruse used in the past to fool potential invaders into mistaking women for men. The other is a rectangular embroidered covering revealing only the eyes. Many women choose not to wear the niqâb today, but it is part of a centuries-old tradition that helped protect the face from the wind, sand, and scorching sun in these areas.

Traditional dress and mask of Bandar Abbas and Qeshm © Hamed Saber / Flickr

ARTICLE BY PRACHI TENDULKAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

http://www.us-iran.org/resources/2017/8/28/industry-spotlight-textiles

https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/regional-traditions/iranian-plateau/naqsh-embroidery-iran

https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/individual-textiles-and-textile-types/furnishings/tent-panel-iran