INTRODUCTION

Kenya, country in East Africa famed for its scenic landscapes and vast wildlife preserves. Its Indian Ocean coast provided historically important ports by which goods from Arabian and Asian traders have entered the continent for many centuries. Along that coast, which holds some of the finest beaches in Africa, are predominantly Muslim Swahili cities such as Mombasa, a historic centre that has contributed much to the musical and culinary heritage of the country. Inland are populous highlands famed for both their tea plantations, an economic staple during the British colonial era, and their variety of animal species, including lions, elephants, cheetahs, rhinoceroses, and hippopotamuses. Kenya’s western provinces, marked by lakes and rivers, are forested, while a small portion of the north is desert and semidesert. The country’s diverse wildlife and panoramic geography draw large numbers of European and North American visitors, and tourism is an important contributor to Kenya’s economy.

With a long history of musical and artistic expression, Kenya enjoys a rich tradition of oral and written literature, including many fables that speak to the virtues of determination and perseverance, important and widely shared values, given the country’s experience during the struggle for independence.

Kenya’s many peoples are well known to outsiders, largely because of the British colonial administration’s openness to study. Anthropologists and other social scientists have documented for generations the lives of the Maasai, Luhya, Luo, Kalenjin, and Kikuyu peoples, to name only some of the groups. Adding to the country’s ethnic diversity are European and Asian immigrants from many nations. Kenyans proudly embrace their individual cultures and traditions, yet they are also cognizant of the importance of national solidarity; a motto of “Harambee” (Swahili: “Pulling together”) has been stressed by Kenya’s government since independence.

Ethnic groups and languages

Women from The Bantu Tribe

The African peoples of Kenya, who constitute virtually the entire population, are divided into three language groups: Bantu, Nilo-Saharan, and Afro-Asiatic. Bantu is by far the largest, and its speakers are mainly concentrated in the southern third of the country. The Kikuyu, Kamba, Meru, and Nyika peoples occupy the fertile Central Rift highlands, while the Luhya and Gusii inhabit the Lake Victoria basin.

Nilo Saharan Tribe

Nilo-Saharan—represented by the languages of Kalenjin, Luo, Maasai, Samburu, and Turkana—is the next largest group. The rural Luo inhabit the lower parts of the western plateau, and the Kalenjin-speaking people occupy the higher parts of it. The Maasai are pastoral nomads in the southern region bordering Tanza nia, and the related Samburu and Turkana pursue the same occupation in the arid northwest.

The Afro-Asiatic peoples, who inhabit the arid and semiarid regions of the north and northeast, constitute only a tiny fraction of Kenya’s population. They are divided between the Somali, bordering Somalia, and the Oromo, bordering Ethiopia; both groups pursue a pastoral livelihood in areas that are subject to famine, drought, and desertification. Another Afro-Asiatic people is the Burji, some of whom are descended from workers brought from Ethiopia in the 1930s to build roads in northern Kenya.

In addition to the African population, Kenya is home to groups who immigrated there during British colonial rule. People from India and Pakistan began arriving in the 19th century, although many left after independence. A substantial number remain in urban areas such as Kisumu, Mombasa, and Nairobi, where they engage in various business activities. European Kenyans, mostly British in origin, are the remnant of the colonial population. Their numbers were once much larger, but most emigrated at independence to Southern Africa, Europe, and elsewhere. Those who remain are found in the large urban centres of Mombasa and Nairobi.

Swahili people

The Swahili (mostly the products of marriages between Arabs and Africans) live along the coast. Arabs introduced Islam into Kenya when they entered the area from the Arabian Peninsula about the 8th century AD. Although a wide variety of languages are spoken in Kenya, the lingua franca is Swahili. This multipurpose language, which evolved along the coast from elements of local Bantu languages, Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Hindi, and English, is the language of local trade and is also used (along with English) as an official language in the Kenyan legislative body, the National Assembly, and the courts.

Religion

Freedom of religion is guaranteed by the constitution. More than four-fifths of the people are Christian, primarily attending Protestant or Roman Catholic churches. Christianity first came to Kenya in the 15th century through the Portuguese, but this contact ended in the 17th century. Christianity was revived at the end of the 19th century and expanded rapidly. African traditional religions have a concept of a supreme being who is known by various names. Many syncretic faiths have arisen in which the adherents borrow from Christian traditions and African religious practices. Independent churches are numerous; one such church, the Maria Legio of Africa, is dominated by the Luo people. Muslims constitute a sizable minority and include both Sunnis and Shīʿites. There are also small populations of Jews, Jains, Sikhs, and Bahaʾis. In remote areas, Christian mission stations offer educational and medical facilities as well as religious ones.

Daily life and social customs

View of Nairobi city at night

As is true of many developing African countries, there is a marked contrast between urban and rural culture in Kenya. Attracting people from all over the country, Kenya’s cities are characterized by a more cosmopolitan population whose tastes reflect practices that combine the local with the global. Nairobi’s nightlife, for instance, caters to youth interested in music that varies from American rhythm and blues, hip-hop, and rock to Congolese rumba. The city contains movie theatres and numerous nightclubs where patrons can dance or shoot pool; for children there are water parks and family amusement centres.

For all the modernization and urbanization of Kenya, however, traditional practices remain important. Rituals and customs are very well documented, owing to the intense anthropological study of Kenya’s peoples during the period of British colonial rule; oral literature is safeguarded, and several publishing houses publish traditional folktales and ethnographies.

Ugali

Kenyan cooking reflects British, Arab, and Indian influences. Foods common throughout Kenya include ugali, a mush made from corn (maize) and often served with such greens as spinach and kale. Chapati, a fried pitalike bread of Indian origin, is served with vegetables and stew; rice is also popular. Seafood and freshwater fish are eaten in most parts of the country and provide an important source of protein. Many vegetable stews are flavoured with coconut, spices, and chilies. Although meat traditionally is not eaten every day or is eaten only in small quantities, grilled meat and all-you-can-eat buffets specializing in game, or “bush meat,” are popular. Many people utilize shambas (vegetable gardens) to supplement purchased foods. In areas inhabited by the Kikuyu, irio, a stew of peas, corn, and potatoes, is common. The Maasai, known for their herds of livestock, avoid killing their cows and instead prefer to use products yielded by the animal while it is alive, including blood drained from nonlethal wounds. They generally drink milk, often mixed with cow’s blood, and eat the meat of sheep or goats rather than cows.

Urban life in Kenya is by no means uniform. For example, as a Muslim town, Mombasa stands in contrast to Nairobi. Although there are numerous restaurants, bars, and clubs in Mombasa, there are also many mosques, and women dressed in bui buis (loose-fitting garments that cover married Muslim women from head to toe) are common.

Rural life is oriented in two directions—toward the lifestyles of rural inhabitants, who still constitute the majority of Kenya’s population, and toward foreign tourists who come to visit the many national parks and reserves. Although agricultural duties occupy most of the time of rural dwellers, they still find occasion to visit markets and shopping centres, where some frequent beer halls. Mobile cinemas also provide entertainment for the rural population.

Kenya observes most Christian holidays, as well as the Muslim festival ʿId al-Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan. Jamhuri, or Independence Day, is celebrated on December 12. Moi Day (recognizing Daniel arap Moi) and Kenyatta Day, both in October, honour two of the country’s presidents, while Madaraka (Swahili: Government) Day (June 1) celebrates Kenya’s attainment of self-governance in 1964.

Costumes of Kenya

Kitenge

Kitenge or chitenge (pl. fitenge) is an East African, West African and Central African fabric similar to sarong, often worn by women and wrapped around the chest or waist, over the head as a headscarf, or as a baby sling. Kitenges are colourful pieces of fabric. In the Coastal area of Kenya, and in Tanzania, Kitenges often have Swahili sayings written on them.

Kitenges are similar to kangas and kikoy, but are of a thicker cloth and have an edging on only a long side. Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Sudan, Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, Senegal, Liberia, Rwanda, and Democratic Republic of the Congo are some of the African countries where kitenge is worn. In Malawi, Namibia and Zambia, kitenge is known as Chitenge. They are sometimes worn by men around the waist in hot weather. In some countries like Malawi, Chitenges never used to be worn by men until recently when the president encouraged civil servants to buy Malawian products by wearing Chitenge on Fridays.

Kitenges (plural vitenge in Swahili; zitenge in Tonga) serve as an inexpensive, informal piece of clothing that is often decorated with a huge variety of colors, patterns and even political slogans.

The printing on the cloth is done by a traditional batik technique. These are known as wax prints and the design is equally as bright and detailed on the obverse side of the fabric. These days Wax prints are commercially made and are almost completely roller printed. Fancy prints are roller printed with the designs being less colorful or detailed on the obverse side. Many of the designs have a meaning. A large variety of religious and political designs are found as well as traditional tribal patterns. The cloth is used as material for dresses, blouses and pants as well.

Uses

Kitenges can be used on occasions and in many ways either symbolically or for practical reasons. kitenges are used in different settings to convey messages. The following list demonstrates uses of the cloths.

- In Malawi, Chitenjes are customary for women at funerals.

- They are used as a sling to hold a baby across the back of a mother. They can hold the baby at the front as well, particularly when breast feeding.

- kitenges are given as gifts to young women.

- They are sometimes tied together and used as decorative pieces at dinner tables.

- When women go to the beach, often the Kitenge is wrapped around the bathing suit for modesty or to shield cold air.

- kitenges can be framed or otherwise hung up on the wall as a decorative batik artwork.

Kitenges have also become very popular as fashion statements in urban pop culture with youth in Africa. Kitenges are incorporated in clothing items such as hoodies, trousers, and accessories such as bags.

Kanga

The kanga, is a colourful fabric similar to kitenge, but lighter, worn by women and occasionally by men throughout the African Great Lakes region. It is a piece of printed cotton fabric, about 1.5 m by 1 m, often with a border along all four sides (called pindo in Swahili), and a central part (mji) which differs in design from the borders. They are sold in pairs, which can then be cut and hemmed to be used as a set.

Whereas kitenge is a more formal fabric used for nice clothing, the kanga is much more than a clothing piece, it can be used as a skirt, head-wrap, apron, pot-holder, towel, and much more. The kanga is culturally significant on Eastern coast of Africa, often given as a gift for birthdays or other special occasions.[1] They are also given to mourning families in Tanzania after the loss of a family member as part of a michengo (or collection) into which many community members put a bit of money to support the family in their grief. Kangas are also similar to Kishutu and Kikoy which are traditionally worn by men. The Kishutu is one of the earliest known designs, probably named after a town in Tanzania, they are particular given to young brides as part of their dowry or by healers to cast off evil spirits. Due to its ritual function they do not always include a proverb.

The earliest pattern of the kanga was patterned with small dots or speckles, which look like the plumage of the guinea hen, also called “kanga” in Swahili. This is where the name comes from, contrary to the belief that it comes from a Swahili verb for to close.

Origins

Kangas have been a traditional type of dress amongst women in East Africa since the 19th century.

Merikani

According to some sources, it was developed from a type of unbleached cotton cloth imported from the US. The cloth was known as merikani in Zanzibar, a Swahili noun derived from the adjective American (indicative of the place it originated). Male slaves wrapped it around their waist and female slaves wrapped it under their armpits. To make the cloth more feminine, slave women occasionally dyed them black or dark blue, using locally obtained indigo. This dyed merikani was referred to as kaniki. People despised kaniki due to its association with slavery. Ex-slave women seeking to become part of the Swahili society began to decorate their merikani clothes. They did this using one of three techniques; a form of resist dying, a form of block printing or hand painting. After slavery was abolished in 1897, Kangas began to be used for self-empowerment and to indicate that the wearer had personal wealth.

Lenços

According to other sources, the origin is in the kerchief squares called lencos brought by Portuguese traders from India and Arabia. Stylish ladies in Zanzibar and Mombasa, started to use them stitching together six kerchiefs in a 3X2 pattern to create one large rectangular wrap. Soon they became popular in the whole coastal region, later expanding inland to the Great Lakes region. They are still known as lesos or lessos in some localities, after the Portuguese word.

Manufacture

Until the mid-twentieth century, they were mostly designed and printed in India, the Far East and Europe. Since the 1950s kangas started to be printed also in the city of Morogoro in Tanzania (MeTL Group Textile Company) and Kenya (Rivatex and Thika Cloth Mills Ltd are some of the largest manufacturers in Kenya) and other countries on the African continent.

Appearance

- Generally Kangas are 150 cm wide by 110 cm long.

- They are rectangular and always have a border along all four sides.

- Often kangas have a central symbol.

- Most modern kangas bear a saying, usually in Kiswahili.

There are many different ways to wear kangas. One traditional way of wearing the kanga is to wrap one piece as a shawl, to cover the head and shoulders, and another piece wrapped around the waist. Kangas are also used as baby carriers.

Shuka

Even if you’ve never heard of shuka cloth, there’s a high chance you’ve seen it in pictures. Often red with black stripes, shuka cloth is affectionately known as the “African blanket” and is worn by the Maasai people of East Africa.

To give you some brief background knowledge, the Maasai are a semi-nomadic people from East Africa who are known for their unique way of life, as well as their cultural traditions and customs.

Living across the arid lands along the Great Rift Valley in Tanzania and Kenya, the Maasai population is currently at around 1.5 million, with the majority of them living on the Masai Mara National Reserve of Kenya. They are known to be formidable, strong warriors who hunt for food in the wild savannah and live closely with wild animals.

The Maasai identity is often defined by colourful beaded necklaces, an iron rod (as a weapon) and of course, red shuka cloth. While red is the most common colour, the Maasai also use blue, striped, and checkered cloth to wrap around their bodies. It’s known to be durable, strong, and thick — protecting the Maasai from the harsh weather and terrain of the savannah.

Shuka’s origins

So how did this traditional clothing come about?

The word “traditional” must be taken with a grain of salt. Before the colonialization of Africa, the Maasai wore leather garments. They only began to replace calf hides and sheep skin with commercial cotton cloth in the 1960s.

But how and why they chose shuka cloth is still unclear today. There are a few schools of thought. One of them is traced back through centuries — fabrics were used as a means of payment during the slave trade and landed in East Africa, while black, blue, and red natural dyes were obtained from Madagascar. There were actually records of red-and-blue checked “guinea cloth” becoming very popular in West Africa during the 18th century.

Another interesting explanation is that the Maasai cloth was brought in by Scottish missionaries during the colonial era. The Africa Inland Mission was established in 1895, and until 1909 Kenya was its only operation. This sounds like a logical explanation — after all, shuka cloth does resemble the Scottish plaid or tartan patterns.

These days, however, shuka cloth is usually manufactured in Dar es Salaam and even in China, bearing text such as “The Original Maasai Shuka” on the plastic packaging. Ironically, the Maasai really do buy and wear shukas made in China, packaged in plastic.

Revolution of the Maasai blanket

Recent years have seen shuka cloth popping up in the fashion world and gaining fame all over the globe.

A Kenyan clothing label has taken inspiration from the patterns of the shuka cloth to produce clothes and accessories in vibrant tribal prints. Nairobi-based Wan Fam Clothing was founded by brothers Jeff and Emmanuel Wanjala to pay homage to Kenya’s Maasai culture.

By turning a traditional garment into fashionable urban wear, they hope to meet the increased demand for more local products that highlight their heritage. Even Louis Vuitton featured red and blue Maasai checks in their Spring/Summer collection 2012.

Shuka cloth’s past may still be a mystery, but it looks set to conquer the future.

Tribes and their traditional dresses

Kenya has over 42 different tribes, all with distinct cultural identities, traditions, and dialects. This cultural diversity in Kenya has given rise to a blend of traditional attires which a number of ethnic groups have managed to keep to date..

While Kenya is known for its wildlife and landscape diversity, it’s also admired for its vibrant people and varied culture. The country has over 42 different tribes, all with distinct cultural identities, traditions, and dialects. This cultural diversity in Kenya has given rise to a blend of traditional attires. A number ethnic groups have managed to keep their traditional garments. However, most of the ethnic traditional dressing has been replaced by western clothing.

Compiled below are some of the traditional dresses that are still worn by different communities in Kenya.

Maasai

Despite civilization and western cultural influences that have swept across most tribes in Kenya, the Maasai have stuck to their traditions and culture, making them a symbol of Kenyan culture. Their unique culture, dress-code, and placement along game parks have made them tourist attractions. The Maa speakers find pride in their culture and mostly express it through their dressing, rituals and ceremonies.

Their initial traditional attires were made of animal skins but today, the official wear is a red cotton known as shuka (sheet/loincloth). It signifies their earth, independence, courage, and blood all given to them by nature and is wrapped around the torso. To add more appeal to the look, loads of beaded jewelry are placed around the neck and arms. Grouped by age-sets, their dressing varies by age or group, clan, occasion, sex or personal style. Though red is their main color, you can find them in Shuka ranging from blue, green, stripped and checked.

Women make the colorful necklaces, bracelets, and pendants to show their identity and position in the society through body ornaments and painting. The decorative and colorful designs demonstrate social standing, creativity, beauty, and prosperity. Unmarried girls wear large, flat beaded discs around their necks. Brides wear elaborate and heavy jewels that hang down to their knees making it difficult for them to walk. Married woman wears elongated leather earring. Their necks are decorated with elegantly beaded collars which are higher in front and lower in back. However, the colors differ from one clan to another. A young warrior hair is braided in sophisticated patterns and wear earrings, bracelets and beaded necklaces that hang down the front and back of their bodies. Symbols are worn to show their achievements. Errap, worn around the top part of the arm is made of leather with coils of metal wire in front and back shows a man killed another man. Olawaru, a headdress made from a lion’s mane, shows a man killed a lion. Enkuwaru, a headdress made from ostrich plumes shows a man fought a lion but never killed it.

The Maasai faces are decorated with white limestone chalk in elaborate non-symbolic patterns while the hair is colored red with ochre and animal fat. Red beads are connected with blood, blue to heavens and gods, while green to prosperity, fertility, and land.

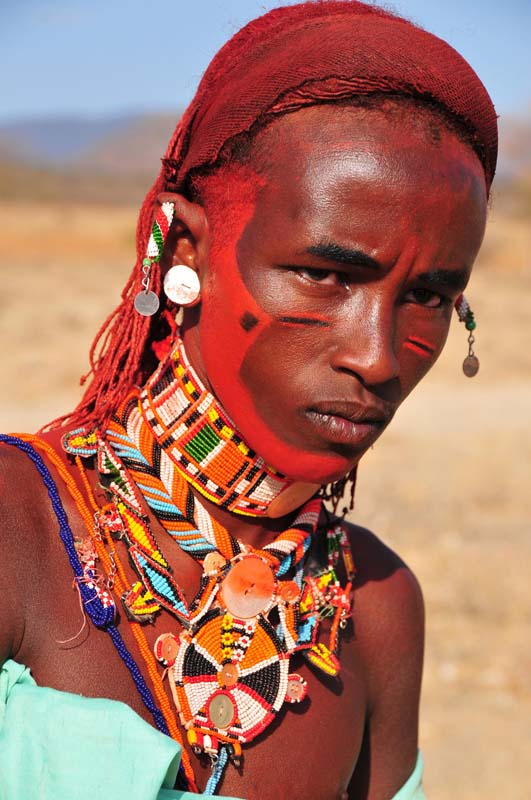

Samburu

/GettyImages-637563890-e465202eb7e04293a21d8ab7c272a6d1.jpg)

The Samburu are related to the Maasai. They share a few traditions and speak the Maa language. However, the Samburu are more aggressive with their traditions than their Maasai cousins. The Samburu are yet to discard their traditional tribal attire in favor of Western-style dressing because it is unmanly and results in curses. Like the Maasai, they wear shukas and impressive jewels with beaded necklaces, elaborate headdresses, and tons of brightly colored bracelets. To add glamor to that, their faces are painted red with red ochre and they wear headdresses of a striking set of brightly colored feathers.

Circumcised men wear extravagant feather headdresses made of beads, polished ostrich shell and feathers and are not allowed to meet with women. The headdresses are worn with loads of bright beaded jewelry made by the women who wear giant amount of jewelry. The most famous of their jewel is the ornate beaded collars. They also paint their faces like men using portions made up of ground chalk and ochre. The body painting is used to highlight their best features.

Turkana

Although mostly making headlines for drought and insecurity reasons, the Turkana are one of the tribes in Kenya that have managed to preserve their unadulterated culture identities. They are also related to the Maasai and are nomadic pastoralists with livestock keeping the core of their culture. Unlike the Maasai and Samburu, the Turkana do not have complex customs or strong social structures. However, they are as colorful with their dressings as their relatives. Turkana men decorate their hair with bright crimson dye blended from the special colored soil. Women adorn themselves with traditional jewelry and piles of beaded necklaces. The amount, style, and quality of jewels a woman wears determines her social status. Women also wear stunning animal sleeveless garments that are embroidered with polish ostrich shell to stress her look.

The Swahili

The Swahili tribe is rich in historical and cultural heritage. They came to be after intermarriages between the Cushites, Bantus, Arabs, Hindi, Portuguese, and Indonesian who gave rise to a new culture, people, and language. The Swahili tribe live in the coastal towns in Kenya including Mombasa, Malindi and Indian Ocean islands of Lamu. Due to the huge Arabic culture influence, Islamic traditions rules apply in their food, clothing, and lifestyle.

The Swahili tribe traditional garment is a long white robe popularly known as Kanzu in Swahili and a small, white, round hat with elaborate embroidery. On their part, Swahili women wear long dresses known as buibui and cover their head with a hijab and other hide their faces with a veil. In Nairobi and other towns in Kenya where western influence is more spread, Swahili men wear western-styled pants and shirts as every day wear only or them to revert to their traditional attires on religious ceremonies and Fridays which is the official Muslims prayer day.

Other Tribes

Other tribes in Kenya tend to have a mix of the popular Kanga, Kitenge and Kikoi. Kanga is a Kenya traditional clothing used in almost all Kenyan households as a baby carrier, headgear, and a waist or torso wrap. It has multicolored designs and is loved for its educative Swahili and English sayings. Kitenges are similar to Kangas and serve the same purpose but are thicker and have an edging on the long side. They are also used to make contemporary clothing serving as material for shirts, dresses and pants.

Both women and men wear the Kitenge on special occasions like ceremonies. Kikoi is also popular among both men and women. It is also used a beach wrap, beach or picnic blanket, scarf, shawl, table cloth, table runner. While many predict a cultural drought in coming years, all is not lost as the as long as such garments are around and the likes of Maasai, Samburu, Turkana and Swahili hang on to their cultural dresses.

The traditional dress of Kenya has lots of variants, because almost every tribe has their own idea how the national attire should look. Still, Kenyan national clothing is very bright, colored and heavily decorated.

– Rutuja Shinde