Rugmani Venkat is a fashion educator and lectures on History of Fashion at various institutes in Mumbai and Pune. She believes in inspiring students to dig more into the treasure trove of fashion and gain richer knowledge. She is an alumni of PV Polytechnic, SNDT, Juhu, besides being a post-graduate in History and Ancient Indian culture from Mumbai.

Fashionista of yore

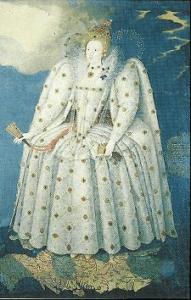

Resplendent with a superabundance of luxe and finery, the recherché display of fashion at the court of Queen Elizabeth I, the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty, outflanked every other European counterpart of its time, surmises Rugmani Venkat.

Tall, red- haired, thin, bony with a hook nose, are the words that would occur to anyone who glanced at Her Highness, not without awe, of course. At the age of 25, Elizabeth ascended the throne of England after her half-sister Mary I’s death.

During Queen Mary I’s reign of four years, more than two hundred and eighty Protestants had been burned at the stake at her savage outburst against non-confirmers of Catholicism. Her marriage to King Philip of Spain had made her even more unpopular. However when the childless Mary fell prey to influenza, she declared Elizabeth her successor before she succumbed to her illness.

In 1558, the lion-hearted Queen Elizabeth or ‘Good Queen Bess’ or ‘Gloriana’ as she was called, was possessed with a determination of sorts that ensured that no pair of eyes should ever ignore her or even make an attempt to censure her. A shrewd practitioner of diplomacy, she enforced new reforms. Being a Protestant woman, she granted freedom to Jews and Catholics to practice their own religion, though she established a Protestant church. For the first 30 yrs of her reign, England was at peace and grew richer and prosperous, although Spain remained a fly in the ointment.

At the commencement of her reign, a portrait of that time depicts her as wearing an upper dress which appears to be a sort of a cloak of black velvet and ermine, fastened on the chest and open below, revealing a waistcoat and kirtle or petticoat of white silk or silver embroidered with black. She wears a simple ruff along with a gauze kerchief or scarf, knotted.

She then on chose to adorn her person unlike the way her grandmother had, but indignantly made her own personal statements in dress. Enraged at the Pope for condemning her ruff which had been albeit simple, she set out to soothe her ego by making every aspect of her clothing stand out singularly and in excess. Red hair loaded with jewels, a gargantuan ruff at her neck, a bombastic farthingale, a jeweled stomacher piqued to an extreme V, portentous petticoats and a bushel of pearls strewn on her person, she seemed truly outstanding and captivating to all, though there were Catholic plots against her at the same time.

Within less than a year into her reign, garments were empowered with lavish surface treatment, and sewn with a greater artistry than before, bearing a Hispanic influence that endowned them with a stiff, artificial appearance. Though Spain was England’s enemy then, it did not deter her from incorporating two Spanish elements – the standing Ruff and the Farthingale in her attire. At a later stage she also embraced French elements in her costume.

It is said that half her reputation must be credited to the standing ruff. The ruff assumed notorious proportions during the reign of Elizabeth I. Her ruffs were surpassed by none in Europe. The striking innovation introduced by her was an enormous ruff rising gradually from the front and then rising ambitiously high, nearly upto the head at the back. This ruff was parted at the front. At the back it seemed to give the illusion of a halo of glory usually painted in portraits of holy angels or gods in the past. This gave the personality of Elizabeth, an immense thrust. Ruffs gave Her Majesty a stately countenance. She engaged a Fleming to ensure that her ruffs exhibited exclusivity.

Though it delighted Her Highness immensely to experiment with aggrandizing the dimensions of her own ruffs, she sternly imposed restrictions on those of her subjects. Her sumptuary laws prohibited their stature and size for all, excepting her. She went to the extent of stationing grave sentinels at every gate of the city to cut all ruffs that were in excess of the prescribed length.

The partlet that had been instrumental in covering the woman from neck to chin was relinquished. It perhaps, for her was a vestige of her mother’s generation of women who were submissive and could also be beaten up if their husbands found their behavior unsatisfactory. Elizabeth who had faced censure and abandonment in her childhood after the hanging of her mother, would have wished to destroy such symbols of submissiveness. She was thus responsible for the ‘partial revelation’ of the bosom. From this newly ‘discovered’ bosom descended a long incessant stomacher that ended in a sharp V which seemed to scream out in indignance against any allegation made on its virgin mistress.

The behemothic vardingale jutted out horizontally. This Spanish farthingale assumed preposterous dimensions during Queen Bess’s reign. The farthingale was a petticoat that was reinforced with hoops of graded sizes at intervals in order to project fullness. It had been invented by the Spanish to reflect their pride as one of their explorers Columbus had discovered America. It was bell-shaped, cage-shaped or drum-shaped. She often wore the drum shaped verdingale or farthingale which seemed to bestow upon its wearer the appearance of standing in the drum. At a riper phase of her rule, the Queen developed a particular affection for the wheel farthingale which was a French invention. In her best known portraits, she is attired in one. The ornamental stiffened sections at the waist gave the appearance of a wheel.

Her reign witnessed not only an absolute change in the manners and carriage of female dress, but also a phenomenal increase in the articulation and bejeweling of attire. Queen Elizabeth nursed a great liking for embroidery as well as symbology. Embroidery in those times was quintessential for every woman’s education. Besides adding interest, it also contained hidden messages. Serpents were perceived as a symbol of wisdom. Ears and eyes were viewed as suggesting knowledge. At Queen Elizabeth’s behest, all these three symbols were embroidered onto her clothing. She deemed that her gloves should be truly as exquisite as the rest of her trappings. Her gloves began to be embroidered with animal figures.

Image from luminarium.org The fan,the indispensable lady’s companion made its first appearance in England under her reign. Fans were made of feathers and suspended from the girdle by a gold or silver chain. Handles were composed of gold, silver or ivory of elaborate workmanship, and were sometimes inlaid with precious stones. As a New Year’s gift, Elizabeth once received a fan with a handle studded with diamonds.

She commissioned portraits of herself in her most impressive clothing and hung them up all around her

Kingdom. Towards 1570-80, her costume was even more elaborately worked and fabricated in fresh spring colours, perhaps an effort to capture her fading charms.

The cap or coif was banished, and in its place she adopted the round bonnet that earlier had been the prerogative of men. She displayed a particular liking for a starched, conch headdress of a bombastic volume for some occasions, and also a kind of transparent mantle. Her flaming tresses were adorned with countless curls, and decorated with jewels and ropes and, at the end of her reign, even with feathers.

Her passions were dancing and hunting. Her courtiers indulged in poetry, singing and music. She drowned her worries by practicing her dances every day, for there were a great many like the Pavane, a slow and solemn dance, Lavolta, a leaping and twisting dance, Brawl, a dance from France, and more, some of them being very difficult. Elizabeth’s age was an age of drama where theatre enriched life in England, subtlely mocking the serious attitude of the Spanish.

Her personality was nothing but a strong manifestation of the tiger-blood that had been present in her father King Henry the VIII, who had in his time been a fashion diva among men. Poets would compare her to Venus or the moon, and she undoubtedly derived enjoyment in playing that act. Artists would paint her with a rainbow or other spiritual symbols. Elizabeth, the virgin Queen did not attempt the least to dispel any notions of this kind, but instead encouraged her own portrayal as an allegorical figure instead of a down to earth Queen. Artificiality was the buzzword for her, the fashionista who demanded the same artificiality in the costume of her courtiers.

The decrees passed by her changed fashion by the week. Anyone who dressed in an outdated hue or a style that had become passé was at once noticed by the hawk eyed Queen who made no small matter of it. He would immediately be made the butt of her sarcastic ridicule and consequently be mocked by all at court. To fall out of her favour was equivalent to death for her courtiers, who tried to outdo one another in attire whether at court or at sport.

It is said that more than two thousand dresses made up her wardrobe. Almost all were bestowed upon her by her devoted subjects who were too well aware of her obsession with clothes and finery and her fondness for flattery and praise. The Queen’s own attempts to conceal and defy her age were instrumental in increasing the detailing in dress and make-up after 1580. Then, for the first time in a hundred years, skirts became shorter, revealing feet and shoes.

Today, self-expression is always cited as the major functions of wearing clothing. Elizabeth’s fervent love for elaboration and artistry in costume reiterated that all the time. She bestowed upon the sixteenth century female costume its remarkable character.

In the reign of the Virgin Queen, the English passion for fashion reached a highpoint. Having inherited her father’s love for fine clothes and jewellery, she advanced further, giving a new dimension to display of dress.

One observes that even at the end of her life in her seventies, she still perhaps desired to pass for a Venus and exude charms and make a statement. Towards the end of her reign, a reduction against elaboration began to take place. She then wore the ruff in the same simple innocuous size as that of the time of its origin.

Had she lived longer, what would have ensued in her fashion journey? Would fashion have peregrinated in the same manner as we have viewed in the history of dress? Would the good Queen Bess have revived the simplicity of attire of her mother’s time yet again to stand out again in contrast to the previous over elaboration judiciously practiced by her? One will never know.

There is no doubt that Queen Elizabeth ushered in an era of matchless elegance and stateliness in costume in England and made it an outstanding fashion leader of its time.

Bibliography

An illustrated dictionary of Historic costume, – James Robinson Planche’

20,000 years of fashion – Francois Boucher