Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean about 1,100 nautical miles (2,000 km; 1,300 mi) northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about 110 are permanently inhabited—and more than 500 islets, amounting to a total land area of about 18,300 square kilometres (7,100 sq mi). The most outlying island is Ono-i-Lau. 87% of the total population of 883,483 live on the two major islands, Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. About three-quarters of Fijians live on Viti Levu’s coasts, either in the capital city of Suva or in smaller urban centres such as Nadi—where tourism is the major local industry—or Lautoka, where the sugar-cane industry is paramount. Because of its terrain, the interior of Viti Levu is sparsely inhabited.

The majority of Fiji’s islands formed through volcanic activity starting around 150 million years ago. Some geothermal activity still occurs today on the islands of Vanua Levu and Taveuni. The geothermal systems on Viti Levu are non-volcanic in origin, with low-temperature (c. 35–60 degrees Celsius) surface discharges.

Humans have lived in Fiji since the second millennium BC—first Austronesians and later Melanesians, with some Polynesian influences. Europeans first visited Fiji in the 17th century, and after a brief period as an independent kingdom, the British established the Colony of Fiji in 1874. Fiji operated as a Crown colony until 1970, when it gained independence as the Dominion of Fiji. A military government declared a Republic in 1987 following a series of coups d’état. In a coup in 2006, Commodore Frank Bainimarama seized power. When the High Court ruled the military leadership unlawful in 2009, President Ratu Josefa Iloilo, whom the military had retained as the nominal head of state, formally abrogated the 1997 Constitution and re-appointed Bainimarama as interim prime minister. Later in 2009, Ratu Epeli Nailatikau succeeded Iloilo as president. After years of delays, a democratic election took place on 17 September 2014. Bainimarama’s FijiFirst party won 59.2% of the vote, and international observers deemed the election credible.

Fiji has one of the most developed economies in the Pacific through its abundant forest, mineral, and fish resources. The currency is the Fijian dollar, with the main sources of foreign exchange being the tourist industry, remittances from Fijians working abroad, bottled water exports, and sugar cane. The Ministry of Local Government and Urban Development supervises Fiji’s local government, which takes the form of city and town councils.

| Republic of Fiji | |

FLAG

COAT OF ARMS |

|

Location of Fiji (red) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Suva 18°10′S 178°27′E |

| Official languages | Fijian English Fiji Hindi |

| Recognised regional languages | Rotuman |

| Ethnic groups

(2016) |

|

| Religion

(2007) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Fijian |

|

Independence |

|

| • from the United Kingdom | 10 October 1970 |

| • Republic | 7 October 1987 |

|

Area |

|

| • Total | 18,274 km2 (7,056 sq mi) (151st) |

| • Water (%) | negligible |

|

Population |

|

| • 2018 estimate | 926,276 (161st) |

| • 2017 census | 884,887 |

| • Density | 46.4/km2 (120.2/sq mi) (148th) |

| Currency | Fijian dollar (FJD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (FJT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13[11] (FJST[12]) |

CULTURE

While indigenous Fijian culture and traditions are very vibrant and are integral components of everyday life for the majority of Fiji’s population, Fijian society has evolved over the past century with the introduction of traditions such as Indian and Chinese as well as significant influences from Europe and Fiji’s Pacific neighbours, particularly Tonga and Samoa. Thus, the various cultures of Fiji have come together to create a unique multicultural national identity.

Fiji’s culture was showcased at the World Exposition held in Vancouver, Canada, in 1986 and more recently at the Shanghai World Expo 2010, along with other Pacific countries in the Pacific Pavilion.

TEXTILES OF NEW FIJI

TAPA CLOTH

Tapa is unique in its material composition. It is not a woven fabric, and its manufacture engages communal activity rather than technological aids. The raw material comes from the inner bark of the mulberry tree, or sometimes other sources, such as the breadfruit tree. The making of tapa involves hammering the strips of mulberry tree bark into shape over hard timber logs.

The origins of the manufacturing process are thought to be have been brought into the South Pacific by (Polynesian) communities who left China thousands of years ago bringing with them the techniques that are still in use today. The early colonial adventurers remarked on the sound of tapa being fashioned into long strips as one of the first sounds heard when approaching a village.

Traditionally, this activity is the work of women in the community who sit together, beating and flattening the matt of fibres into sheets of all sorts of sizes and strengths ready for whatever designs are to be applied by the particular village or community. The hammering is often accompanied by laughter and singing as the women sit around the logs in the shade of a tree, or designated shelter.

The designs are then added in various ways but are usually applied by stencilling or rubbing the motif onto the sheets across a rubbing board. The pigments are sourced locally, usually dark brown in colour, and are sometimes applied by a paintbrush crafted from a pandanus nut. The finished tapa was originally used as clothing for men (a sort of second skin), as bedding, or as partitioning in homes.

In day-to-day life there was a constant need for tapa cloth given that it was used for practical as well as for ceremonial purposes. When used for clothing, it would of course be subject to wear, and could be repaired if necessary, by patching the bark cloth. When used for ceremonies, huge lengths with applied designs were made. Usually they represented the village or community in one way or another. After ceremonies were over, the tapa could be cut up and distributed as gifts.

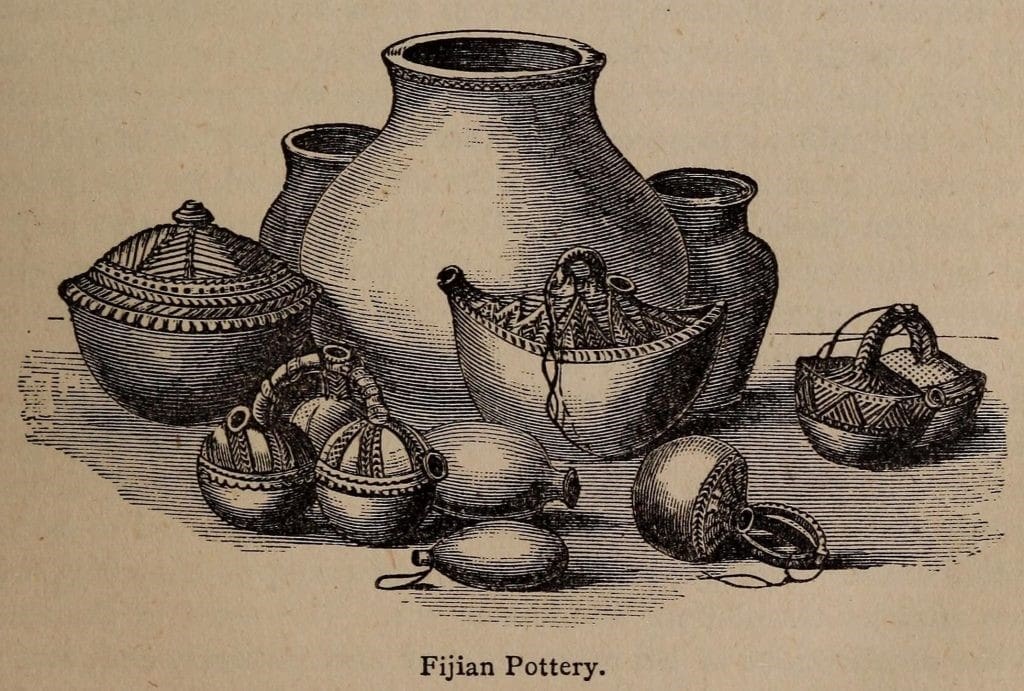

POTTERY

A craft that dates from the original settlement of Fiji around 1290 BC, pottery-making is still practiced in the lower Sigatoka Valley, the islands of Kadavu and Malolo, western Vanua Levu,the Rewa Delta and the province of Ra. Each district has its own distinct signature in its pottery style. Today the technique and division of labour differ little from those of pre-European contact times. Sometimes the men dig the clay, but it is almost always the women who are the potters. The clay is first kneaded, and then sand is added to control shrinkage and to improve the texture. The mixture is left to dry for a short period before being worked into its final form.

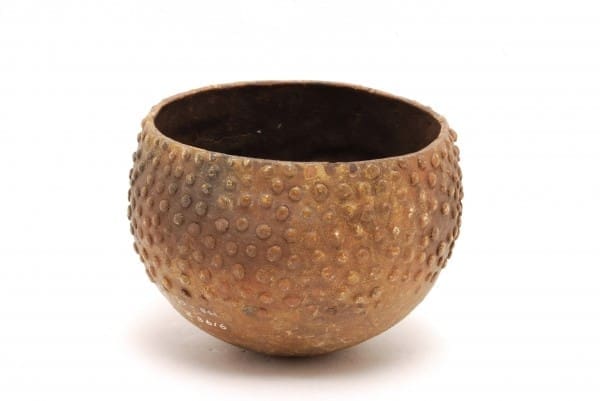

Lapita period bowl (courtesy Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

The tools used by today’s potters are also the same as those used in the past: a rounded stone, a large pebble or a wooden paddle for beating; apiece of coconut husk for rubbing the clay; a shell or stick for ornamenting; and a cushion of leaves on which to place the work during the molding process. Pottery wheels were unknown to ancient Fijians and are still not used. Instead, a saucer-like section is shaped for the bottom of the pot or bowl and the item is progressively built up withslabs, strips orcoils. The sides are shaped by beating the clay with a paddle or pebble. Considering the implements used, the Fijians achieve remarkable symmetry.

After the object is shaped and finished with moistened fingers or a smooth stone, it is dried for several days and fired for an hour in a fire made from brush, reeds or coconut fronds. Fijian pottery is not glazed – instead, certain plants are rubbed on the finished objects as a kind of varnish to improve water-holding qualities.

MAT AND BASKET WEAVING

Interest in weaving from visitors helps keep the skills alive (courtesy Daku Resort)

Whereas pottery is a skill shared by very few villages, basket and especially mat-plaiting is a universally practiced art – every village girl has learned how to weave a mat or ibe by the time she is 10 years old. Palm fronds or the long fibrous pandanus leaves are vital construction materials in Fijian culture. The traditional bure (Fijian home) is constructed from plaited pandanus or palm fronds; pandanus mats are woven into floor coverings, bedrolls, fans and baskets. Almost every home in Fiji, whether in a village or town, has at least several mats for use as rugs or for sleeping on. They are considered an important element in the wealth of the Fijian family and are traditionally given at weddings, funerals or during the visits of high chiefs.

WOOD CARVING

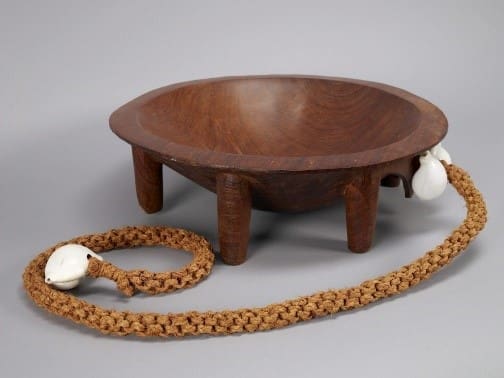

Tanoa or Kava Bowl

Woodcarving is a declining art in Fiji, no doubt another victim of the modern era. The woodcarver’s role was a highly specialized one, important because of the cultural value of the items he produced. The war club, for example, was a vital part of Fijian culture. Not only was it the primary weapon in a warrior’s arsenal, it was a symbol of authority used in ceremony and dance. Likewise, the tanoa, or yaqona bowl, also played (and still plays) an important part in Fijian society. Artist clans were so specialized that carvers in the old days only produced one particular kind of artifact – say clubs or yaqona bowls – and that was it.

JEWELRY OF FIJIANS

There is a huge variety of Traditional Pacific Island Jewelry from numerous different Pacific cultures. Traditional Pacific Island Jewelry was originally made using neolithic tools. Many of these gems made with shark teeth and obsidian. The materials were those found in nature such as shells, teeth, bone, bush fiber, feathers, stone, wood and turtle shell. As soon as Pacific Cultures came in contact with Europeans, they started to incorporate glass trade beads.

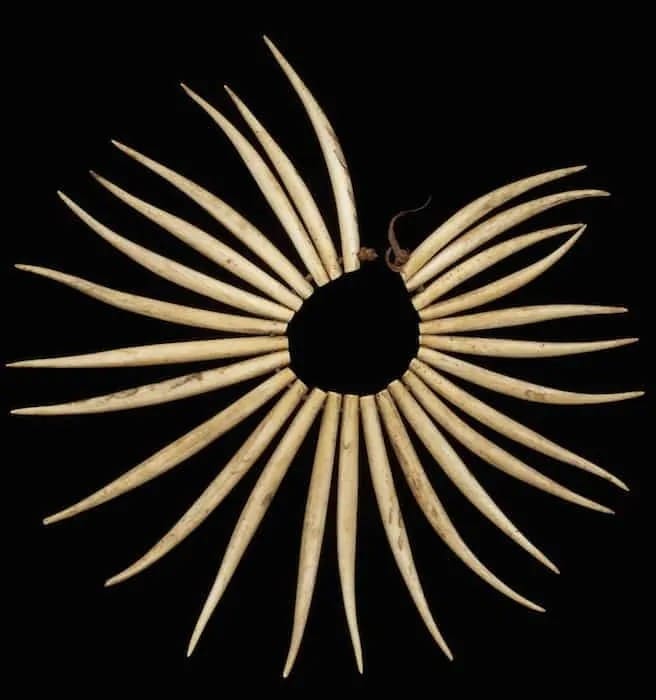

Wasekaseka Fijian whale tooth necklace.

Made from split and reshaped whales teeth on a sennit cord.

Fijian Breastplate

Made of whale teeth and black pearl shell.

CLOTHING OF FIJIANS

The traditional attire was loin cloths for men and grass skirts for women. Skirts were short for single women, and long for married women, with girls wearing virgin locks before marriage. Most females had the lower parts of their bodies decorated with tattoos after their first menstruation, as an initiation from girlhood into womanhood. Chiefs dressed more elaborately.

Modern Fiji’s national dress is the sulu, which resembles a skirt. It is commonly worn by both men and women. One type worn by both men and women is the ‘Sulu vaka Toga’ pronounced Sulu vakah Tonga which is a wraparound piece of rectangular material which is elaborately decorated with patterns and designs of varying styles this is for more casual and informal occasions. Many men, especially in urban areas, also have Sulu vaka taga which is a tailored sulu and can be tailored as part of their suit. Many will wear a shirt with a western-style collar, tie, and jacket, with a matching Sulu vaka taga and sandals, this type of sulu can be worn to a semi formal or formal occasion. Even the military uniforms have incorporated the Sulu vaka taga as part of their ceremonial dress.

Women usually wear a multi-layered Tapa cloth on formal occasions. A blouse made of cotton, silk, or satin, of often worn on top. On special occasions, women often wear a tapa sheath across the chest, rather than a blouse. On other occasions, women may be dressed in a chamba, also known as a sulu i ra, a sulu with a specially crafted matching top.

There are many regional variations throughout Fiji. Residents of the village of Dama, in Bua Province Fiji wear finely woven mats called kuta, made from a reed.

While traditional and semi-traditional forms of dress are still very much in use amongst indigenous Fijian culture, there is a greater influence for Western and Indian Fashion in urban areas as in neighboring developed nations.

REFRENCES

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_Fiji#:~:text=Modern%20Fiji’s%20national%20dress%20is,by%20both%20men%20and%20women.

By- Janvi Nagada (MSc. in Textile and Fashion Technology)