Togo, country of western africa. lome, the capital, is situated in the southwest of the country and is the largest city and port. Until 1884 what is now Togo was an intermediate zone between the states of Asante and Dahomey, and its various ethnic groups lived in general isolation from each other. In 1884 it became part of the Togoland German protectorate, which was occupied by British and French forces in 1914. In 1922 the league of Nations assigned eastern Togoland to France and the western portion to Britain. In 1946 the British and French governments placed the territories under United Nations trusteeship. Ten years later British Togoland was incorporated into the gold coast, and French Togoland became an autoomous republic within the French Union. Togo gained independence in 1960. The economy rests largely on agriculture, although the country’s extensive phosphate reserves are also significant.

Cultural Life

Like other African peoples, the Togolese have a strong oral tradition. Little has been done, however, to promote vernacular literature. Before independence there were a few Togolese writers using French. Since independence, regional (especially Ewe) literature emerged with the works of several novelists and playwrights. Founded in 1967, the African Ballet of Togo has aimed at popularizing the finest traditional dances. The country’s national archives and national library are centred in Lomé, as is the Palais de Lomé, the former residence of colonial-era rulers that now is home to a contemporary art museum and a botanical park.

Holidays observed in Togo include those celebrated by the Christian population, such as Easter, Assumption, Whitmonday, All Saints day, and Chrstmas. The country’s Muslim community observes ʿĪd al-Fiṭr, which marks the end of Ramadan, and ʿĪd al-Aḍḥā, which marks the culmination of the hajj rites. Other holidays include Liberation Day (January 13), which commemorates the anniversary of the coup of 1967; Independence Day (April 27); and the anniversary of the failed attack by dissidents on Lomé in 1986, observed on September 23.

Religion

According to a 2012 US government religious freedoms report, in 2004 the University of Lomé estimated that 33% of the population are traditional animists, 28% are Roman Catholic, 20% are Sunni Muslim, 9% are Protestant and another 5% belonged to other Christian denominations. The remaining 5% were reported to include persons not affiliated with any religious group. The report also noted that many Christians and Muslims continue to perform indigenous religious practices.The CIA World Factbook meanwhile states that 44% of the population are Christian, 14% are Muslim with 36% being followers of indigenous beliefs.

Christianity began to spread from the middle of the 15th century, after the arrival of the Portuguese and Catholic missionaries. Germans introduced protestantism in the second half of the 19th century, when a hundred missionaries of the Bremen Missionary Society were sent to the coastal areas of Togo and Ghana. Togo’s Protestants were known as “Brema,” a corruption of the word “Bremen.” After World War I, German missionaries had to leave, which gave birth to the early autonomy of the Ewe Evangelcal Church.

The Block

African cultures have an enduring textile history and this block features two traditional Togolese fabrics. On a background of richly textured weaving, shot with gold, an embroidered African elephant stands before the cascading Akrowa Falls. Elephants were declared ‘protected’ by French colonial authorities; however, the current elephant population in Togo has decreased dramatically nonetheless. Today these great creatures are found mostly in the country’s game preserves.

The famed Akrowa Falls, one of the most visited tourist sites in the country, plunge 35 metres down into a large pool surrounded by green jungle and citrus trees. Blockmaker Antoinette Hounye has framed the scene with pieces cut from lace yardage made in Holland for the Togolese market. Such yard goods often come studded with rhinestones or other embellishments and are a popular choice for creating special evening wear.

African wax prints

Africa is known for its cultural and artistic traditions. Any tourist visiting Africa will be charmed by the breath taking prints and colors used in their everyday costumes. The elegant attires and beautiful fabrics are regarded with respect by textile curators of various cultural backgrounds. The pride of African culture and heritage is displayed through their fabrics which have distinct styles, and forms that indicate the ethnic diversity of the country. The main method of decorating cloth in Africa is dyeing. It is a main business in many places in Africa and specialist skills are developed in the process of dyeing clothes.

Cloth dyeing is the main source of income for woman from Labe, West Africa. In some places nearly everyone, including men and children are involved in this process. Cloth production is Africa not only varies from place to place, but is also influenced by societal change. Indigo dyeing is done by woman in Yoruba, and Soninke of West Africa, but among Hausa, this task is undertaken by men. The traditional and non industrial nature of dyeing and the way it is practiced makes it all the more fascinating. African traditional methods of dyeing clothes have now become a part of the contemporary art.

Majority of the weavers use only locally produced dyes, and hence only a limited number of shades are available. Brown, green, yellow, and red are mostly used, and by far, the most important color of African dyes has been indigo. Over the centuries, a vast majority of clothes were being produced by combining the natural white color with indigo blue. Very fine quality of clothes were dyed in dark indigo and then dyed with more indigo paste by specialist people so as to give it a glazed sheen. These are extremely expensive and are worn as face veils by nomads throughout North Africa.

Resist Dyeing:

This method is extremely popular in West African countries like Nigeria, Ghana, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Benin, and Sierra Leone. Various methods are applied to protect some parts of the cloth while other parts are dyed. Tie and dye, sew and dye, batik, and using cassava paste resist are most common methods of resist dyeing. In tie and dye method, small areas of cloth are tied using raffia strings before dyeing. Sew and dye is a method, where designs are sewn on the clothes and the stitches are picked later to reveal a light on the dark pattern. In batik method, melted wax is applied on the fabric to resist the dye. This will be a combination of paraffin wax and bees wax.

Bees wax will stick to the fabric, while paraffin wax will allow some cracking, which is the characteristic of some batik. Then the cloth is either dipped or painted with colorful dyes. When the cloth is dyed, the color is absorbed by the other areas where wax is not applied. This method is popular all over Africa and Indonesia. Cassava paste is similar to batik, where a paste is applied on the cloth mostly through a stencil that will resist dye from penetrating into that part of the cloth. Batik designs are mostly used in wrap around skirts.

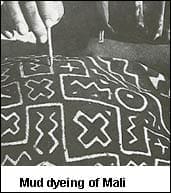

Mud Dyeing:

Women of Mali make a special kind of hand dyed cloth known as mud cloth used during special occasions like birth, marriage, and death. Techniques for dyeing this cloth and motifs are passed down through generations from mothers to daughters. No two clothes will have identical patterns, color combinations or designs. The colors, symbols etc of this cloth reveal a persons social status, and national identity. This cloth is usually dyed in black with white designs. The cloth is first prepared for dyeing by soaking pounded leaves of Bogolon, a native tree of Mali in a special solution. This solution is dark in color and allows the dye to adhere with the cloth. Mud dyes are made by rich, iron mud taken from ponds mixed with water and is fermented up to one year. This mud dye is applied on the cloth using sticks, reeds, feathers, strips of bamboo etc. The background of the cloth is painted leaving the design to remain white. Later on the cloth is washed with solutions prepared with leaves to bind the cloth and the dye strongly. Traditionally this cloth is dyed with black and white color, cut other colors like grey and rust are also used. Mud cloth is believed to posses supernatural powers, and protects hunters.

African art in the limelight:

During the past decade, cloth dyeing sector has started to operate on a large scale. Many associations are now formed to support the cloth dyers in places like Labe, Pita, Mali and Guinea. Initially dyeing was a family business carried down through the generations, and each dyer had their own version of designs, and made their own dyes with the natural materials available. Now, with latest advancements, most of the dyers are switching to supplement the local dyes and inputs with manufactured inputs from other areas like Banjul. The increasing global demand for African dyed clothes has also made the import of inputs necessary.

African textiles are now given a new significance. Modern textile designers are inspired by the work of traditional African artists. Apart from fulfilling the basic need for covering, African fabrics reveals the artistic expression of weavers, dyers, and cloth designers. African textile dyeing revolves around their own family and ethnic group reinforcing religious and social patterns.

African fancy print

The costly produced wax fabrics are increasingly imitated by alternative ways of manufacturing. The so-called “fancy fabrics” are produced in a printing procedure. Costly designs are printed digitally.

Fancy fabrics in general are cheap, industrially produced imitations of the wax prints and are based on industry print. Fancy fabrics are also called imiwax, Java print, roller print, le fancy or le légos. These fabrics are produced for mass consumption and stand for ephemerality and caducity. Fancy Fabrics are more intense and rich in colors than wax prints and are printed on only one side.

As for wax prints, producer, product name and registration number of the design are printed on the selvage. Even the fancy fabrics vary with a certain fashion. The fabrics are limited to amount and design and are sometimes exclusively sold in own shops.

At first the fancy prints were made with engraved metal rollers but more recently they are produced using rotary screen-printing process.

The production of these imitation wax print fabrics, allow those who cannot afford the European imported wax prints to be able to purchase these. The fancy print designs often mimic or copy the designs of existing wax print designs but as they are cheaper to make, manufacturers tend to take risks and experiment with new designs.

Wax print cloth production

Prévinaire’s method for the production of imitation batik cloth proceeds as follows. A block-printing machine applies resin to both sides of the fabric. It is then submerged into the dye, in order to allow the dye to repel the resin covered parts of the fabric. This process is repeated, to build up a coloured design on the fabric. Multiple wooden stamp blocks would be needed for each colour within the design. The cloth is then boiled to remove the resin which is usually reused.

Sometimes the resin on the cloth can be crinkled in order to form cracks or lines that are known as “crackles”. The English- and Dutch-produced fabrics tended to have more cracking in the resin than those produced in Switzerland. Due to the lengthy stages of its production, wax prints are more expensive to make than other commercial printed fabrics but their finished designs are clear on both sides and have distinct colour combinations.

Wax print manufacturers

After a merger in 1875, the company founded by Prévinaire became Haarlemsche Katoenmaatschappij (Haarlem Cotton Company). The Haarlemsche Katoenmaatschappij went bankrupt during the First World War, and its copper roller printing cylinders were bought by van Vlissingen’s company. In 1927, van Vlissingen’s company rebranded as Vlisco.

Before the 1960s most of the African wax fabric sold in West and Central Africa was manufactured in Europe. Today, Africa is home to the production of high quality wax prints. Manufacturers across Africa include ABC Wax, Woodin, Uniwax, Akosombo Textiles Limited (ATL), and GTP (Ghana Textiles Printing Company); the latter three being part a part of the Vlisco Group. These companies have helped reduce the prices of African wax prints in the continent when compared to European imports.

An African success story: Togo princesses of wax print

Colourful, patterned fabric with cult status in Africa has become all the rage on this season’s catwalks. The wax printed fabric is worth its weight in gold. In Togo, in the 1970s, a group of women nicknamed the “Nana Benz” made their fortune with it. Today, a new generation of “Nanettes” are taking up the mantle but they face new challenges trying to keep the business alive. Our reporters find out more about this African success story.

Hidden deep in the textile district of the Togolese capital Lomé, lies an entirely female realm: the world of the “Nana Benz”. These businesswomen, often illiterate but extremely resourceful, built a textile empire in the 1970s and ’80s that spanned all of West Africa.

They specialized in the sale of tchigan, Dutch wax-printed fabric, renowned for its vibrant colours and exceptional quality. The Nana Benz was the continent’s first female millionaires – possibly even billionaires – and their success marked the start of the emancipation of African women. With their huge turnover, they built luxury villas in the residential areas of Lomé, bought apartments in Europe and imported the first German sedans, the famous Mercedes-Benz. With this last achievement, their nickname was born.

Since then, Porsches have replaced the Mercedes and the reign of the Nana Benz has weakened. In the early 2000s, they faced intense Chinese competition, with fabric made in Shanghai and sold at prices 10 times cheaper flooding the Togolese market.

African textile & fashion industry needs development

The textile and fashion industry of Africa has great potential and there needs to be a strategy to exploit this potential and develop the textile and fashion sector, in order to revive the African economy, said Niger fashion designer and stylist Alphadi during the recently held traditional cloth fair, ‘Loincloth Fest’ in the Togolese capital city of Lome.

Mr. Alphadi, also known as Sidhamed Seidnaly, was speaking during a roundtable business conference on ‘Development of the textile and fashion industry: Challenges and Prospects’, held during the Loincloth Fest, which was a part of the ‘Day of Textile’ festival organized by Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Togo (CCIT).

The Niger designer explained during the conference that it is necessary to build a whole development policy of textile sector and expand the fashion industry in the continent to boost pale African economy.

According to Mr. Alphadi, developing the textile and fashion industry of African nations can help designers in these countries to make them known in the international market, and create an image for them in the global fashion industry.

It is necessary to develop the different sectors in the textile industry such as silk, raffia fibres and other innovative materials, which can help boost the African textile sector, he added.The event, organized by the CCIT, was aimed at perpetuating the culture of using loincloth in Togo, and boosting as well as promoting the loincloth business in Lome, which is the hub of loincloth industry in West Africa.

Loincloth is a one-piece garment, made of barks or leather, kept in place with the use of a belt, traditionally used as innerwear or swimsuits by inhabitants.

bibliography-

https://www.france24.com/en/reporters/20190927-togo-nanettes-princesses-wax-print-printed-fabric-textile-africa-fashion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_wax_prints

https://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/3416/african-textile-dyeing http://udel.edu/~orzada/africa.htm.

http://www.library.cornell.edu

By Nidhi Singh