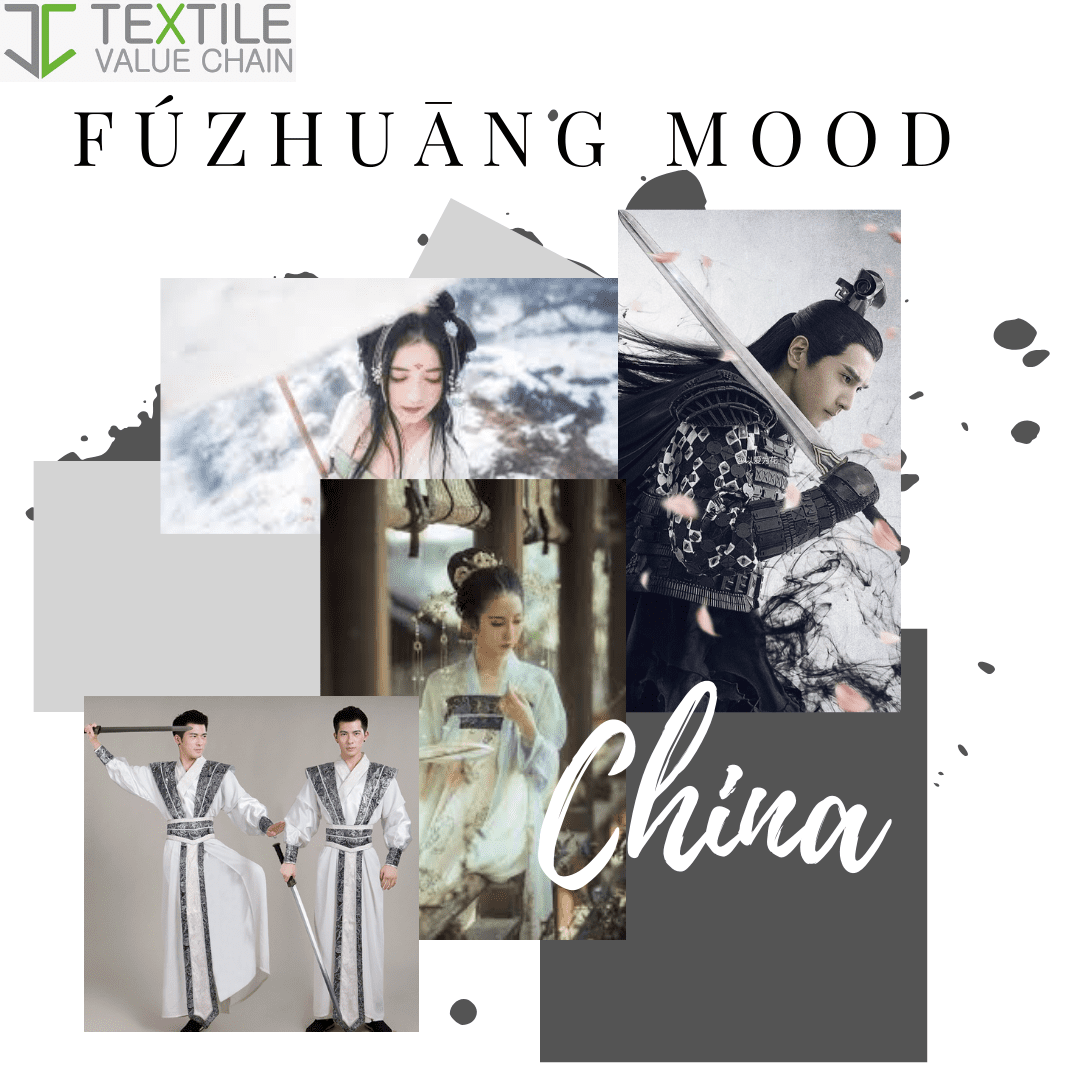

TEXTILES AND COSTUMES OF CHINA

Introduction

Clothing may seem like a mundane part of our everyday lives. To many, dress is merely a practical concern that warrants no more than superficial notice. But in every culture clothing is one of the most powerful and ubiquitous forms of visual communication.

By using visual clues provided by clothing, people quickly ‘place’ each other, making guesses about the gender, social status, occupation, ethnic or national identity, and so on of those they encounter. By manipulating the same sets of signals, people can declare their individuality, indicate their beliefs, or signify their membership within various groups through how they dress. At any given time and place there are conventional ways of expressing meaning through one’s clothing, but over time these conventions change in response to changed political circumstances, technology, and fashion. This unit will explore the role clothing played within Chinese culture. In China, by Ming and Qing times, clothing indicated not only differences in class and gender, but also ethnicity, as the two major ethnic groups, Han Chinese and Manchu, wore distinct clothes. This unit will begin by looking at these traditional patterns, then consider how the great social and political changes of the twentieth century altered this system.

China is an extremely large country — first in population and fifth in area, according to the CIA — and the customs and traditions of its people vary by geography and ethnicity.

According to the administrative divisions of the People’s Republic of China including Hong Kong and Macau, there are three levels of cities, namely provincial-level[1] (consists of municipalities and SARs[2]), prefecture-level cities, and county-level cities. As of January 2020 the PRC has a total of 686 cities: 4 municipalities, 2 SARs, 293 prefectural-level cities (including the 15 sub-provincial cities) and 387 county-level cities (including the 38 sub-prefectural cities and 10 XXPC cities) not including any cities in the claimed province of Taiwan.

Four cities are centrally administered municipalities, which include dense urban areas, suburbs, and large rural areas: Chongqing (28.84 million), Shanghai (23.01 million), Beijing (19.61 million), and Tianjin (12.93 million).

Chinese Culture: Customs & Traditions of China

Chinese Architecture

China has a unique and time-honored architectural tradition, dating back to the Zhou era 2,500 years ago. Discover the reasons behind its features and how China’s architecture reflects Chinese culture. Since ancient times, several types of architecture have been traditionally built by the Chinese, and they are introduced here.

General Features of Chinese Architecture

Wooden buildings had intricate roof frameworks.

Since ancient times, the people built wooden buildings, structures built with rammed earth, and buildings and structures built with stone or brick. Each of these kinds of construction had different features. The buildings were built to survive the frequent earthquake, typhoon and flood disasters and to be easier to rebuild. Along with survivability and ease of renovation, the buildings reflected and helped to propagate social order and religion.

Preference for Lumber Construction

China’s culture originated thousands of years ago along the Yellow River and Yangtze River. In the environment of the river basins, the seismic activity and frequent flood disasters prompted the people to build flexibly using wood for most buildings.

The thick forests then were a ready supply of lumber. The wooden architecture has distinctive features that changed little from the Zhou Dynasty (1045–221 BC) era up until early modern times when China adopted Western architecture.

The basic features of traditional lumber architecture were a stamped earth base, load bearing wooden pillars that were not planted into the foundation, and slightly flexible brackets. These design features made the buildings resilient to earthquake and storms, and they also allowed for reconfiguration, expansion and reconstruction if the buildings were damaged.

Heavy Overhanging Roofs

On large buildings, such as this in the Forbidden city, roofs might overhang the walls by several meters.

A noticeable feature of the traditional wooden buildings are the heavy ceramic tiled roofs with wide eaves and slightly upturned corners. The builders considered it important to cover wooden buildings with overhanging roofs. This was to protect the building from weathering since wood rots much faster when it is wet. The wide eaves also provided shade in the summer, and in the winter, the slanted sunlight warmed the buildings.

As you can see in the picture of a building in the Forbidden City, in traditional buildings, the eaves were not supported by columns past the walls. The eaves might overhang the walls by several meters. Since ancient times, durable ceramic tiles were the favorite roofing material, but they were heavy.

Rammed Earth Buildings

A Hakka earthen building, Fujian

In places where a clan’s compound faced the danger of attack such as the Hakka villages in Fujian, people built earthen buildings 土楼 (tǔlóu). In these compounds, thick walls of rammed earth and sometimes bricks and stone were built in a circle without windows, and inside dwellings were constructed.

Chinese Language

Chinese Language Use Worldwide

Mandarin (standard Chinese) is the most used mother tongue on the planet with over 800 million native speakers.

The two world languages with over a billion users are English and Mandarin. English is used by over 1.8 billion people worldwide and Mandarin is used by over 1.3 billion people, including people using them as a second language or business language.

China’s Many Languages

China has many languages, the most famous being Mandarin (China’s national language) and Cantonese (spoken in Southeast China). There are many dialects and minority languages in China.

Traditional Festivals

Spring Festival

The most important festival in China is the Spring Festival. The Spring Festival marks the beginning of the Chinese lunar New Year, so the first meal is rather important. People usually eat jiaozi or dumplings shaped like a crescent moon on that special day. As for recreational activities during the Sping Festival, the Dragon Dance and Lion Dance are traditionally performed.

Yuanxiao Festival (Lantern Festival)

The Lantern Festival is on the 15th day of the first Chinese lunar month. It is closely related to Spring Festival. It is traditionally a time for family reunions. The displaying of lanterns is a big event on that day, and another important part of the Festival is eating Yuanxiao, which is small dumpling balls made of glutinous rice flour.

Qingming Festival (Tomb Sweeping Day)

Qingming, meaning clear and bright, is the day for mourning the dead. It falls in early April every year. It corresponds with the onset of warmer weather, the start of spring plowing, and of family outings. Springtime, especially in North China, is the windy season, just right for flying kites. It is not surprising that kite flying is very popular during the Qingming season.

Duanwu Festival (Dragon Boat Festival)

The Duanwu Festival falls on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese lunar calendar. For thousands of years, Duanwu has been marked by eating zongzi and racing dragon boats. Zongzi is a kind of pyramid-shaped dumpling made of glutinous rice and wrapped in bamboo leaves. Duanwu is also known as the Dragon Boat Festival, because dragon boat races are held during the festival, especially in southern China.

Mid-Autumn Festival

Mid-Autumn Festival falls on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Because the full moon is round and symbolizes reunion, the Mid-Autumn Festival is also known as the festival of reunion. People in different parts of China celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival in different ways. But one traditional custom has remained and is shared by all Chinese. This is eating the festive specialty: moon cakes —— cakes shaped like the moon.

Chongyang Festival (Double Nine Festival)

The number “nine” belongs to Yang in the theory of Yin and Yang. The ninth day of the ninth lunar month is a day when the two Yang numbers meet. So it is called Chongyang. This festival is usually perfect for outdoor activities. And it is a special day for people to pay their respects to the elderly. It has also been declared China’s day for the elderly.

When one speaks of folk dances in connection with Chinese culture, most people today think of the quaint folk dances of ethnic minorities, forgetting that the forefathers of the “tribe” that would later be referred to as the Han Chinese were perhaps the first Chinese people to make use of ritual dancing. The early Chinese folk dances, like other forms of primitive art, were essentially ritual enactments of superstitious beliefs performed in the hope of a good harvest, or – in the case of the earliest Chinese folk dances – in the hope of a good hunt, since the earliest Chinese folk dances were performed by hunter-gatherer folk.

Though no corresponding written historical source exists, archeologists have found pottery shards in China dating from the 4th millenium BC (about 6000 years ago) which depict dancers brandishing spears and other weapons that were used for hunting. There is thus a direct parallel between the earliest Chinese hunting-dance rituals and the Cro-Magnon paintings on the walls of the caves of Lascaux in south-central France (the Department of Dordogne) that depict the animals hunted by those cave dwellers, and before which, to the flickering flames of a nightly bonfire, hunting dances may well have been performed; both were done in the belief that by performing these rituals, the hunter thus gained power over the hunted.

Much, much later, during the Han (BC206 – CD 220) Dynasty period, when most of the folk dances of the many ethnic minorities of present-day China were developed, the ethnic groups in question had long since become primarily farmers, if not farmer-gatherers, i.e., farmers who supplemented their annual harvest with the gathering of freely growing fruits and nuts as well as with fishes caught from rivers, lakes – and the ocean, where applicable – and of course some hunting, especially with the aid of traps, was practiced. Therefore the folk dances that were developed during this period reflected a superstitious belief that in making ritual sacrifices to the gods in appreciation of the “harvest” (i.e., to include freely growing nuts & berries, fishes, etc.), one could persuade the gods to provide another bountiful harvest in the following year.

Folk dance of Miao ethic group

Folk dance of Miao ethic groupIn spite of modern-day realities, i.e., in spite of the fact that the descendants of these ancient farmer-gatherers now have more stable forms of agriculture – and many of them are no longer employed in agriculture at all, but have office jobs – the ritual dances continue, even if the ancient superstition may have been superseded with a modern belief that in upholding the traditions of the past, including the communal folk dance, one might therewith reinforce social cohesion and help to preserves one’s cultural identity.

Two of the main Chinese folk dances – the Dragon Dance and the Lion Dance – stem from the Han Chinese, even if these have since been borrowed by many other Chinese ethnic minorities. In addition, one of the most elaborate forms of Chinese folk dance, the Court Dance (sometimes referred to as the Palace Dance), was originally adopted by the royal court of a Han Chinese emperor (Emperor Qin of the Qin (BC 221-207) Dynasty), though subsequent Chinese emperors, including those of Mongol or Jürchen/ Manchu background, continued the well-established custom of the Court Dance. Dragon dance and lion dance are usually presented during Chinese Lunar New Year Festival. China Highlights’ new year festival tours offer our customers a great opportunity to celebrate the festival together with real Chinese people.

Food

- Sweet and Sour Pork

Sweet and Sour Pork is one of the classics of Chinese cuisine. No one can reject its sweet and sour mix flavor and bright appearance. Some people don’t eat pork, so some restaurants change it to Sweet and Sour Chicken, which shows how adorable its taste is.

- Kung Pao Chicken

What comes to your mind when ordering Chinese food in a restaurant? I bet your answer would be “Kung Pao Chicken”.

Commonly-seen in the US TV series, Kung Pao Chicken has spread around the world as typical Chinese food. It is basically diced chicken cooked with peanuts, cucumbers, and peppers. This red cuisine is moderately spicy with tender meat and delicious flavor.

- Spring Rolls

Spring rolls are fried pancakes with different fillings in south China. Those from Shanghai and Guangdong are the best known. In the past, the Chinese had the custom of having spring rolls to mark the end of winter and the beginning of spring.

The filling can be either sweet or savory depending on your preference. For a sweet filling, sweetened bean paste is a good choice. For a savory one, Chinese cabbage and shredded pork is particularly popular, while shredded bamboo shoots and mushrooms can be added for good measure. The skins of perfect spring rolls should be crispy, and the filling tender.

- Ma Po Tofu

In 1862, Chengdu had a small restaurant operated by Chen Ma Po. The tofu she cooked was tasty and good-looking. People loved the tofu very much and called it “Ma Po Tofu”.

Ma Po Tofu is actually sautéed tofu in hot and spicy sauce. Its main ingredients are tofu, minced beef (or pork), chilies and Sichuan pepper, which highlight the characteristics of Sichuan cuisine – hot and spicy.

- Dumplings

/chinese-pan-fried-dumplings-694499_hero-01-f8489a47cef14c06909edff8c6fa3fa9.jpg)

Dumplings were invented by a famous doctor of traditional Chinese medicine, Zhang Zhongjing, in more than 1,800 years ago. Doctor Zhang stuffed small dough wrappers with stewing mutton, black pepper and some warming herbs to dispel coldness and treat frostbitten ears in winter. He boiled these dumplings and distributed them to his patients until the coming of the Chinese New Year.

- Wonton

Wonton is a traditional snack originating in North of China. They are also popular in the south. Even its name “wonton” comes from Cantonese. With a variety of packaging, fillings and cooking methods, wonton has all kinds of local flavors.

- In Northern China, wonton is always filled with celery (or cabbage) and minced mutton (or beef or pork).

- In Guangdong area, wonton is usually stuffed with shrimp and minced pork and is served with noodles to make wonton noodles.

- In Hong Kong, wonton is fried in hot oil until it becomes golden and crispy, called “Fried Wonton”.

- In Fujian area, wonton is served with light soup.

- Fried Rice

Yangzhou Fried Rice

Fried rice is a very simple but popular Chinese cuisine. It is a dish of boiled rice which is usually mixed with scallions and minced meat and quickly scrambled with eggs.

Just like wonton, fried rice in different areas also has different flavors.

- Yangzhou (Yeung Chow) Fried Rice: the most popular fried rice in Chinese restaurants, usually consists of rice, shrimp, ham sausage and scrambled with eggs, carrots and green beans.

- Cantonese Fried Rice: stir-fried rice with sausage, preserved meat and minced garlic.

- Fujian Fried Rice: braised shrimp, chicken, mushroom, scallops, carrot, egg, tomato and potato starch are made into a thick sauce and mixed with rice.

- Chow Mein

The name “Chow Mein” comes from Cantonese. Chow means “fried” and “mein” means noodles. So Chow Mein is actually a dish of fried noodles served with chop suey. Even the widely-loved Pad Thai is evolved from Chinese Chow Mein.

- Peking Duck

Peking Roast Duck

Peking Roast Duck is a renowned Beijing dish with a worldwide reputation. The high-quality duck meat, roasted using wood charcoal, looks reddish, with crisp skin and tender meat, and is known as “one of heaven’s delicacies”.

- Hot Pot

Chengdu Hotpot

Hot Pot is definitely the last -but not least- dish you’ve got to try in China! It is so beloved that I bet you can’t find any Chinese who don’t like it.

Hot pot is a stew of meat and vegetables cooked in a simmering pot of soup stock. It can be roughly divided into two types: spicy and not spicy, but there are also hundreds of different flavors. Almost all the ingredients you can think of can be cooked in a hot pot, making it one of the most comprehensive dish in the world.

Ethnic groups in China

The 55 minorities ethnic groups are Achang, Bai, Bonan, Bouyei, Blang, Dai, Daur, Deang, Dong, Dongxiang, Dulong, Ewenki, Gaoshan, Gelao, Hani, Hezhe, Hui, Jing, Jingpo, Jinuo, Kazak, Kirgiz, Korean, Lahu, Li, Lisu, Luoba, Manchu, Maonan, Menba, Miao, Mongolian, Mulao, Naxi, Nu, Oroqen, Ozbek, Pumi, Qiang, Russian, Salar, She, Shui, Tajik, Tatar, Tibetan, Tu, Tujia, Uigur, Wa, Xibe, Yao, Yi, Yugur, Zhuang.

According to the population, the major ethnic groups are Zhuang, Uyghur, Hui, Manchu, Miao, Yi, Tujia, Tibetan, Mongol, Dong, Buyei, Yao, Bai, Korean, Hani, Li, Kazakh and Dai.

The minorities of China mainly live in the vast areas of the west, southwest and northwest of China. You can see minorities scattered in Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, Hunan, Hubei and many other places. Need to mention here, Yunnan, the province with 25 ethnic minorities, is a great destination to explore different minorities like Yi minority, Bai minority, Naxi Minority, Hani minority, Dai minority etc.

Textiles of China

Silk production, characteristic of China’s earliest civilization, has been an enduring feature of Chinese tradition and a distinctive aspect of China’s interaction with other cultures. From China’s Neolithic era, hemp and ramie were cultivated and woven into textiles for clothing and other uses. Wool textiles played a minor role, associated with border peoples of the north and west. Cotton cultivation began at least by the eighth century. By the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), it had become an industry to rival silk production. Though silk retained its role as a luxury fabric and a symbol of Chinese culture, cotton cloth ultimately became a widespread material and an economic staple.

From the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.), silk manufacture comprised a major state-controlled industry. For thousands of years, along land routes through Central Asia and sea routes along the coasts of East and Southeast Asia, silk was both a major commodity and at times a standard medium of exchange. In China’s diplomacy, silk played a stabilizing role, bringing large areas of Inner Asia into the Chinese sphere of influence. At home, silk production was viewed as a moral imperative as well as a practical necessity. The Confucian adage, “men till, women weave,” expresses the essential role of the women in a household in preparing silk yarn and cloth. Later, an increase in industrial specialization encouraged a shift of women’s efforts from weaving to needlework, and yet the spirit of the phrase was preserved. As late as the seventeenth century, the state collected taxes in silk as well as in grain, underscoring the essential value of this human endeavor. Ultimately, the uses of silk expanded to include textiles made for appreciation as art as well as for clothing and furnishings.

Elaborate techniques were developed for producing complex designs, both in the woven cloth itself and in embellishments worked onto the surface. Brocades, weaves with supplementary weft yarns creating complex patterns, were employed in many variations, including the complex lampas weave with its extra binding warps. Kesi, a tapestry weave, perhaps originally developed by Central Asians with wool yarn, came to be highly refined in the works of Chinese weavers of the Song dynasty (960-1279) and later. Embroidery, a means of embellishing a woven fabric with stitches made using a threaded needle, flourished throughout the history of silk textiles in China.

Silk and Diplomacy

The value of silks for diplomatic gifts was recognized early. Confucian texts of the third century B.C.E. mention the practice. During the Song dynasty (960-1279), some diplomatic gifts to border peoples included 200,000 bolts of silk.

The domestication of silkworms, the production of silk fiber, and the weaving of silk cloth go back to at least the third millennium B.C.E. in northern China, and possibly even earlier in the Yangtze River Valley. Archaeological evidence for this survives tombs from that era; pottery objects sometimes preserve the imprint of silk cloth in damp clay, and in some cases layers of corrosion on bronze vessels show clear traces of the silk cloth in which the vessels had been wrapped. Silk was always the preferred fabric of China’s elite from ancient times onward. As a proverbial phrase put it, the upper classes wore silk, the lower classes wore hempen cloth (though after about 1200 C.E. cotton became the principal cloth of the masses).

Depictions of clothed humans on bronze and pottery vessels contemporary with the Shang Dynasty (c. 1550-1046 B.C.E.) of the North China Plain show that men and women of the elite ranks of society wore long gowns of patterned cloth. Large bronze statues from the Sanxingdui Culture of Sichuan, dating to the late second millennium B.C.E., show what appears to be brocade or embroidery at the hemlines of the wearer’s long gowns. Later depictions of commoners portray them in short jackets and trousers or loincloths for men, and jackets and skirts for women. Soldiers are shown in armored vests worn over long-sleeved jackets, with trousers and boots.

Chinese silk textiles of the later first millennium B.C.E. (the Warring States Period, 481-221 B.C.E.) testify to the possibility of making very colorful and elaborately decorated clothing at the time. Surviving textiles also demonstrate the widespread appeal of Chinese silk in other parts of Asia. Examples of cloth woven in the Yangtze River Valley during the Warring States Period have been discovered in archaeological sites as far away as Turkestan and southern Siberia. Painted wooden figurines found in tombs from the state of Chu, in the Yangtze River Valley, depict men and women in long gowns of white silk patterned with swirling figural motifs in red, brown, blue, and other colors; the gowns are cut in such a way that the left panel wraps over the right one in a spiral that goes completely around the body. The gowns of the women are closed with broad sashes in contrasting colors, while the men wear narrower sashes. Bronze sash-hooks are common in tombs from the second half of the first millennium B.C.E., showing that the style of narrow waist sashes lasted for a long time. Elite burials also demonstrate a long-enduring custom of the wearing of jade necklaces and other jewelry.

Chinese Embroidery

The art of embroidery was widespread throughout China in the Han Dynasty (BC 206 – AD 220). Four distinctive styles, or schools, of embroidery emerged at that time, though each would reach their pinnacle after the blossoming of the Silk Road trade created a demand for Chinese goods.

The earliest examples of Chinese embroidery stem from the Zhou Dynasty (1027 – 221 BC). It is unclear whether this was the origin of embroidery because Egypt and Northern Europe also have early examples. Ancient Chinese embroidery was crafted using silk, because spinning from silkworms had already been mastered. Curiously, Chinese embroidery was originally the domain of males; it was only later that Chinese men realized that women were better at it.

The four schools of Chinese embroidery are now designated by the government as a Chinese Intangible Cultural Heritage. They are: Shu embroidery, Xiang embroidery, Su embroidery, and Yue embroidery. Miao Embroidery is a separate style of embroidery from a minority group.

The Shu School of Chinese Embroidery

Shu embroidery has particularly been associated with the city of Chengdu, capital Sichuan Province. Both “Shu” and “Chuan” are abbreviations used for Sichuan, so Shu embroidery has also been called Chuan embroidery. The most salient features of Shu embroidery are:

Lovely pandas feature with Shu embroidery.

- It is tightly stitched — necessary for intricate work (think high-pixel versus low-pixel resolution).

- It excels in the art of mixing threads in a gradually increasing fashion to effortlessly transition from one solid color to another.

- It the natural world. The panda is a current popular motif as Chengdu is the home for the panda.

- It is typically done on soft, satin fabric and makes use of brightly coloured threads.

- It follows strict, tradition-bound principles, that are divided into 12 primary weaving categories which result in 122 subcategories.

- Its products include quilt covers, pillow cases, table cloths, chair cushions, scarves and handkerchiefs.

Shu embroidery can be found in the shops of Chengdu that specialize in such items, such as in the Hongqi Shopping Store chain, with prices as low as 300 Yuan (about $44 USD). Shu embroidery can also be found at the Shu Brocade Academy in Chengdu. For Shu embroidery stores see Chengdu Shopping.

China Highlights’ Chengdu tours provide customers a great chance to explore the city’s remarkable history with a chance to buy Shu embroidery.

The Xiang School of Chinese Embroidery

Xiang embroidery has historically been associated with Hunan Province. “Xiang” is an abbreviation for Hunan, which comes from the Xiang River which runs through the province.

The most salient features of Xiang embroidery are:

This lifelike picture of cranes is an example of Xiang embroidery.

- It deliberately mimics other art forms such as painting, engraving and calligraphy.

- It’s “reversible” with separate imagery on both sides.

- It specializes in a satin look, the depictions have very soft, smooth surfaces.

- Its motifs are typically “broad-brush” humans, birds, animals, and landscapes, among which depictions of lions and tigers dominate.

- It emphasizes few colors, with large solid-color surfaces. Intricate patterns was never the goal, but instead simple and bold.

- Xiang embroidery was much prized in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) especially, but it has won many international awards in expositions since.

The Su School of Chinese Embroidery

Su embroidery derives its name from the abbreviation for Jiangsu Province, which is also the “Su” in the provincial capital Suzhou.

Su embroidery is categorized into Pre and Post Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), when Su embroidery was influenced by both Japanese and Western art, absorbing these and changing forever. The absorption is likely due to the province’s proximity to Japan and the interaction with the West at the time.

The most salient features of Shu embroidery are:

This beautiful picture of flowers illustrates Su embroidery.

- It is renowned for its refinement, its clearly demarcated, delicate lines and its elegant, tasteful overall design.

- It is tightly stitched, similar to Shu embroidery, and uses a thin needle to produce meticulously crafted patterns.

- Its colors are not monochromatic, but consist of the proper mix of different colored threads so as to achieve the desired hue.

- It is “reversible” like Xiang embroidery, though the best Su embroidery masters produced double-sided embroidery where the reverse side was a mirror image of the front.

Su embroidery became so famous during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) that Suzhou was called “City of Embroidery”. Su embroidery was the favorite in the Qing Dynasty court, for royal clothing and wall decoration.

Su embroidery is also popular today, and now is used for general-use products such as handbags. Su embroidery has won recognition at international expositions. The best place to buy Su embroidery is at the Su Embroidery Museum in Suzhou. Find out more on Suzhou Shopping.

The Yue School of Chinese Embroidery

Dragon and phoenix motifs are typical of Yue embroidery.

Yue embroidery (Cantonese Embroidery) is associated with present-day Guangdong Province. (“Yue” is the abbreviation for Guangdong”.)

Though there is little evidence, Yue is believed to the be the oldest embroidery school. According to historical sources, early Yue embroidery used twisted peacock feathers and used horse tail hair to separate colour borders. These are still used today, though mostly for accentuation.

Although Yue Embroidery combines many embroidery schools, there are two characteristics that distinguish the style, these are:

- It generally doesn’t try to create depth such as making things look 3D

- It takes as its most common motifs mythical creatures such as sun-worshipping birds, dragons and phoenixes.

- It is sometimes on cotton rather than silk.

It is especially popular with Chinese expat communities all over the world. Yue embroidery has also won many prizes, including prizes at international expositions. Some of the older exemplars of Yue embroidery fetch outrageous prices at international auctions such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s whenever they appear.

Miao Embroidery

Beautiful embroidery of the Miao minority

Miao embroidery is a unique art of the Miao minority people.

The designs involve propitious animals such as kylin, dragon, phoenix, insect, fish, flowers and fruits. Profuse colors are used, for instance scarlet, pink, purple, dark blue, Cambridge blue, and bottle green.

Miao embroideries can be bought in Southeast Guizhou where China’s largest Miao community is located. Xijiang Miao Village in Kaili is particularly well-known for its embroidery. Embroidery is available on sale in the village.

Costumes of China

Chinese clothing changed considerably over the course of some 5,000 years of history, from the Bronze Age into the twentieth century, but also maintained elements of long-term continuity during that span of time. The story of dress in China is a story of wrapped garments in silk, hemp, or cotton, and of superb technical skills in weaving, dyeing, embroidery, and other textile arts as applied to clothing. After the Chinese Revolution of 1911, new styles arose to replace traditions of clothing that seemed inappropriate to the modern era.

Throughout their history, the Chinese used textiles and clothing, along with other cultural markers (such as cuisine and the distinctive Chinese written language) to distinguish themselves from peoples on their frontiers whom they regarded as “uncivilized.” The Chinese regarded silk, hemp, and (later) cotton as “civilized” fabrics; they strongly disliked woolen cloth, because it was associated with the woven or felted woolen clothing of animal-herding nomads of the northern steppes.

Essential to the clothed look of all adults was a proper hairdo-the hair grown long and put up in a bun or top-knot, or, for men during China’s last imperial dynasty, worn in a braided queue-and some kind of hat or other headgear. The rite of passage of a boy to manhood was the “capping ceremony,” described in early ritual texts. No respectable male adult would appear in public without some kind of head covering, whether a soft cloth cap for informal wear, or a stiff, black silk or horsehair hat with “wing” appendages for officials of the civil service. To appear “with hair unbound and with garments that wrap to the left,” as Confucius put it, was to behave as an uncivilized person. Agricultural workers of both sexes have traditionally worn broad conical hats woven of bamboo, palm leaves, or other plant materials, in shapes and patterns that reflect local custom and, in some cases, ethnicity of minority populations.

The clothing of members of the elite was distinguished from that of commoners by cut and style as well as by fabric, but the basic garment for all classes and both sexes was a loosely cut robe with sleeves that varied from wide to narrow, worn with the left front panel lapped over the right panel, the whole garment fastened closed with a sash. Details of this garment changed greatly over time, but the basic idea endured. Upper-class men and women wore this garment in a long (ankle-length) version, often with wide, dangling sleeves; men’s and women’s garments were distinguished by details of cut and decoration. Sometimes a coat or jacket was worn over the robe itself. A variant for upper-class women was a shorter robe with tighter-fitting sleeves, worn over a skirt. Working-class men and women wore a shorter version of the robe-thigh-length or knee-length-with trousers or leggings, or a skirt; members of both sexes wore both skirts and trousers. In cold weather, people of all classes wore padded and quilted clothing of fabrics appropriate to their class. Silk floss-broken and tangled silk fibers left over from processing silk cocoons-made a lightweight, warm padding material for such winter garments.

Men’s clothing was often made in solid, dark colors, except for clothing worn at court, which was often brightly ornamented with woven, dyed, or embroidered patterns. Women’s clothing was generally more colorful than men’s. The well-known “dragon robes” of Chinese emperors and high officials were a relatively late development, confined to the last few centuries of imperial history. With the fall of the last imperial dynasty in 1911, new styles of clothing were adopted, as people struggled to find ways of dressing that would be both “Chinese” and “modern.”

Cloth and Clothing in Ancient China

The area that is now called “China” coalesced as a civilization from several centers of Neolithic culture, including among others Liaodong in the northeast; the North China Plain westward to the Wei River Valley; the foothills of Shandong in the east; the lower and middle reaches of the Yangtze River Valley; the Sichuan Basin; and several areas on the southeastern coast. These centers of Neolithic cultures almost certainly represent several distinct ethnolinguistic groups and can readily be differentiated on the basis of material culture. On the other hand, they were in contact with each other through trade, warfare, and other means, and over the long run all of them were subsumed into the political and cultural entity of China. Thus the term “ancient China” is a phrase of convenience that masks significant regional cultural variation. Nevertheless, some generalizations apply.

Shang (C. 1550 B.C.E.-1045 B.C.E.) and Zhou (C. 1045 B.C.E. -221 B.C.E.) Dynasties

Tombs of China’s Bronze Age provide evidence that silk, like bronze and jade, was a luxury commodity, important for ritual use. The royal tombs at Anyang, Henan province, reveal that ritual bronze objects and also ritual jades were wrapped in silk before being buried as grave goods. In the tomb of Lady Fu Hao (twelfth century B.C.E.), more than fifty ritual bronzes are known to have been wrapped in silk cloth. Anyang silks included various weaves, damasks as well as plain (tabby) weave, and some examples were embroidered with patterns in chain stitch.

Spectacular finds of Zhou dynasty silks from the Warring States period (453-221 B.C.E.) are identified with the distinctive Zhou culture centered in China’s middle Yangtze River valley. A tomb at Mashan, Hubei province (datable to the fourth century B.C.E.), yielded the following silks: a coffin cover, a silk painting, bags of utensils, costumes on wooden tomb figures, and nineteen layers of clothing and quilts around the corpse itself. Plain silks, brocades, and plain and patterned gauzes were included as well as embroidery in cross-stitch and counted stitch. Analysis of the complex and densely woven Mashan silks has led scholars to suggest that an early form of the drawloom must have been used to produce them.

Other well-known finds from the Zhou culture confirm the early use of silk as a ground for painting, specifically in two third-century B.C.E. pictorial banners used in funerary rituals and then buried with the deceased. A work known as the “Zhou Silk Manuscript,” dated to circa 300 B.C.E., documents the tradition that early Chinese texts were written on silk cloth and bamboo as well as cast in bronze or carved on stone. Examples of shop marks have been found on silks of this period, including a brocade with an impressed seal, suggesting a growing respect for distinctive workshop products and the commercial value of textiles.

Archaeological finds outside China’s traditional borders confirm the scattered early references to China’s export of silk to neighboring lands. In the Scythian tombs at Pazyryk in the Altai mountains of Siberia (excavated in 1929 and 1947-1949) silks datable to 500-400 B.C.E. were found together with textiles of Near Eastern origin. This evidence gives credence to the belief that the Greeks had imported Chinese silk by the fifth or fourth century B.C.E.

Qin (221-206 B.C.E.) and Han (206 B.C.E. -220 C.E.) Dynasties

Having built the first empire of China, Qin Shi Huangdi (best known in the early 2000s for the 1974 discovery of his “terra-cotta army”) built a great palace. Among its remains have been found silks, including brocade, damask, plain silk, and embroidered silk. After the reconsolidation of the empire under Han imperial rule, silk production became a primary industry, with state-supervised factories employing thousands of workers who produced silks and imperial costumes. Officials were sometimes paid or rewarded with silk textiles. As stability declined at the end of the period, textiles and grain replaced coinage as a recognized medium of exchange.

The legacy of the former state of Zhou continued to flourish, as shown by the rich treasures found at the noble tombs at Mawangdui, Hunan province (second century B.C.E.). Here was preserved silk clothing in fully intact robes. In addition there were manuscripts, maps, and paintings on silk, including elaborate funerary banners showing a portrait of the deceased entering an afterworld of cosmic symbols and signs of immortality. Embroidered silks follow patterns seen in the earlier Mashan silks, using chain stitch worked in cloud-scroll patterns. Printed silks found at Mawangdui correspond to a relief stamp found in the tomb of the Second King of Nan Yue (in Guangzhou, datable to before 122 B.C.E.), providing confirmation that techniques and styles had spread throughout the empire.

Han tombs have yielded a variety of silks, including plain weave, gauze weave, both plain and patterned, and pile-loop brocade similar to velvet. More than twenty dyed colors have been identified. Embellishment of woven fabrics included new techniques of embroidery incorporating gold or feathers, as well as block-printing, stenciling, and painting on silk. Later Han silks include a striking number of woven patterns with texts, usually several characters with auspicious meanings. From pictorial representations, scholars have deduced that Han weavers used treadle looms.

Han Dynasty silken banner excavated from tomb in Hunan

Finds in remote areas have added to our understanding of production and commerce relating to silk textiles. Sir Aurel Stein found in Western China a strip of undyed silk inscribed by hand stating the origin, dimensions, weight, and price. A seal impression designates its origin in Shandong province in Northeast China. Other finds established the standard selvage-to-selvage width of Han silk, at between 17½ and 19½ inches (from 45 to 50 centimeters). At Loulan, in the Tarim Basin in the far Northwest of modern China (Xinjiang province), excavated by Stein (1906-1908 and 1913-1914), Han figured silk textile fragments (datable to the third century C.E. or earlier) were found together with an early example of slit tapestry woven in wool. The latter may be a precursor of the later kesi slit tapestry in silk. Finds at Noin-Ula, in northern Mongolia, dated second century C.E., give further evidence of the widespread exchange of silks throughout Asia. Although details of the trade are yet to be fully understood, comments by early writers make clear the admiration for Chinese silks in the Roman world.

Six Dynasties Period (220-589) and the Tang Dynasty (618-907)

Political disunity during the third to sixth centuries brought close interaction with Central Asia, leading to new styles and techniques relating to textile production. Tang silks reflect these closer contacts established during the previous centuries. The Tang maintained an open capital with foreigners among its merchants and varied ethnic and religious groups among its populace. A general shift in weaving techniques distinguishes Tang silk from that of the Han dynasty. While Han patterns were warp-patterned, the weavings of Tang came to be weftpatterned.

Some of the best Tang textiles survive in temples in Japan, where Chinese fabrics have been carefully preserved in Buddhist temples since before the eighth century. The most important of these holdings is that of the Shōsōin (a storehouse dedicated at Tōdai-ji, Nara, in 756, for the donated collection of Emperor Shōmu), which contains various garments and other textiles believed to have been brought back to Japan by Buddhist monks returning from China.

Investigation of Chinese textiles was stimulated by stunning discoveries of well-preserved ancient textiles in Central Asian sites, including Sir Aurel Stein’s expeditions in northwest China and inner Asia (in 1900, 1906-1908, 1913-1916 and 1930). Discoveries at Dunhuang’s Buddhist cave temples yielded a new range of textiles for study, and brought about an early appreciation of the importance of textiles in Buddhist ritual. Such textiles were probably pious offerings made by Buddhists from Central Asia, especially Sogdiana, as well as from China. Many of the silks were sewn into banners or other adornments for Buddhist chapels, or into wrappers for sacred texts (sutra scrolls). A mantle (kashaya) for a Buddhist priest, its patchwork symbolizing the vow of poverty, was also found. Many of the silk textiles have bright patterns, woven or embroidered, while others were adorned after weaving by painting, printing, stenciling, or by dyeing using resist techniques including clamp-resist, wax-resist and tie-dyeing. The weaving techniques documented in these finds include silk tapestry (kesi), gauze, and damasks, as well as compound weft-faced and warp-faced weaves that were probably woven on a drawloom. These finds confirm that patronage of Buddhism encouraged creation of pictorial textiles either woven in the kesi technique or embroidered with highly refined use of stitches (often satin stitch) to create representational effects.

Important examples of Tang silks have been found at Famen Temple, Shaanxi province. Here, a ritual offering datable to C.E. 874 included about 700 textiles including brocades (many with metallic threads), twill, gauze, pongee, embroidery, and printed silk. Among them was a set of miniature Buddhist vestments including a model of a kashaya, an apron (or altar frontal), and clothing, all couched with gold-wrapped threads on a silk gauze ground in patterns of lotus blossoms and clouds.

Tang Dynasty embroidery on plain-weave silk

Song Dynasty (960-1279)

Song weavers brought refinement to textile technology, especially the weaving of satin and of kesi tapestries. Generally the use of gold and silver increased both in embroidery and in woven brocades. Needle-loop embroidery, a detached looping stitch sometimes combined with appliqué of gilt paper, came into use. In Song times as in the Tang, embroidery and tapestry were used for devotional Buddhist images, but now the techniques were also employed to create items for aesthetic appreciation, like paintings, in the form of scrolls or album leaves.

Jin (1115-1234) and Yuan (1279-1368) Dynasties

Silk played a major role in trade, diplomacy, and court life under the Jin dynasty, founded by the Jurchen, a Tatar people, and the Yuan, founded by the Mongols, both non-Chinese ruling houses. Jin and Yuan brocades, notable for rich patterning with gilt wefts of leather or paper substrate, have been a focus of recent exhibitions. Due to the open trade connections encouraged by the Mongol conquests, these silks spread widely. Examples reached the pope through trade and diplomatic gifts. Thus, the cloth of gold favored by Mongol leaders had its counterpart in the panno tartarico of fourteenth-century Europe.

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

By Ming times, weavers employed elaborate drawlooms using up to forty different colored wefts and incorporating flat gold (gilt paper) strips, gold-wrapped threads as well as iridescent peacock feathers to produce their brocades. The Yongle reign (1403-1424) saw a tremendous dedication of resources to the production of diplomatic gifts including textiles for Buddhist purposes, a practice carried over into the Xuande reign period (1426-1435). Excavations at the tomb of the Ming emperor Wanli (reigned 1572-1620) yielded two complete sets of uncut woven silk for dragon robes, as well as silk brocades and patterned gauzes marked as products of the imperial workshops in Nanjing and Suzhou.

By the late sixteenth century, cotton cultivation, which had been encouraged under the Yuan dynasty and expanded further under the Ming, became a major part of the Chinese economy. From at least Tang dynasty times, cotton had been used to make clothing for the lower classes (Cahill [p. 113] observes that “cotton-clad” meant a commoner in medieval Chinese poetry). In subsequent centuries, cotton cloth was associated with the virtues of humility. Ginned cotton was transported south from Henan and Shandong provinces, or shipped north from Fujian and Guangdong, to the Jiangnan region where it would be made into thread and woven into cloth. Cotton thread is noted among Chinese exports to Japan, and white cotton cloth as well as cotton garments of blue or white are recorded among the items exported on the Manila galleon.

Domestically, cotton found wide use in undergarments and in linings for silk (such as in silk garments for ceremonial use), and it also came to be dyed in bright colors and calendered to an attractively polished surface. The most distinctive artistic developments in Chinese cotton textiles are those that survive primarily in rural traditions and folk art relating to minority groups, including the Miao of Guizhou and Yunnan provinces. The primary techniques, resist dyeing (using stencils to apply a paste that would retain white undyed areas), and batik (using wax to reserve undyed areas), had been known in China, along with block printing, tie-dyeing, and clamp-resist, since the Han dynasty, and are found in silk examples preserved from the Tang period. The characteristic blue from indigo, typical of dyed cotton, also reflects an ancient tradition, recorded in detail in Ming dynasty texts.

Anthropologists and historians have noted a shift in importance among China’s women from activities in weaving to embroidery in the seventeenth century. Increasing specialization meant that finished yarn and finished cloth could be purchased routinely. This spurred a rising interest in embroidery among the gentry, and a related rise in the status of embroidery to verge upon that of the fine arts of painting and calligraphy. The Gu family of Shanghai, for example, came to prominence for their distinctive pictorial embroidery style. A manual of embroidery designs compiled by the scholar-calligrapher Shen Linqi (1602-1664), published in woodblock-printed form, set out themes and patterns that inspired embroiderers for centuries.

Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

Study of Qing textiles has focused on the court collections, now in Beijing’s Palace Museum and in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, including wall decorations, curtains, desk frontals and upholstery fabrics, ceremonial and informal costumes, and works of art. When the Qianlong emperor, inspired by scholar-collectors of the late Ming as well as by the precedent of the Song Emperor Huizong (reigned 1101-1125), commissioned scholar-officials to catalog his art collections (producing the Bidian Zhulin and the Shiqu Baoji, published in 1744-1745, 1793, and 1816) these catalogs included examples of kesi and embroidery alongside painting and calligraphy. Qianlong himself may have selected works to be “reproduced” in kesi, including his own painting and poetry and works in his collection of painting and calligraphy.

The Qing emperors were Manchus whose homeland was in the far Northeast beyond China’s traditional borders. When they conquered China, they were quick to adopt the Chinese practice of using gifts of silk, particularly cloth for dragon robes, as a means to bring the powerful leaders of vassal states into their own military bureaucracy. The Qing forebears had been on the receiving end of this practice during the late Ming period. Silk had long been used to pacify border peoples; Song examples are striking, but the practice began before the Han dynasty. Most visible among textiles surviving up to the twenty-first century are the lavish silk brocades bestowed upon Tibetan nobles and preserved in Tibet’s dry climate until recent years.

ANCIENT CHINESE ACCESSORIES

In Ancient China jewelry was an important part of fashion. Jewelry was worn by both genders to show nobility and wealth. The Dragon was a very popular motif for jewelry. The dragon was mostly worn by emperors and the phoenix was worn by empresses. Women wore a lot of jewelry in their hair. What they wore on their heads determined profession or social rank. The typical male head wear were called; jin for soft caps, mao for stiff hats and guan for formal headdress. The basic headdress for women was called ji but there were a lot more elaborations. Officials and academics had a separate set of hats, typically the putout, the wushamao, the si-fang pingding jin; or simply the fangjin and the zhuangzijin. Popular materials used to make jewelry were jade, bronze and gold.

Jade was a very fashionable emblem of Chinese culture. Jade was used to hang from a sash. According to Confucius jade has eleven virtues which include beauty, purity and grace. The Ancient Chinese used two types of jade; Soft Jade (nephrite) and Hard Jade (Jadeite) which was imported from Burma starting in the 1200s.

-Ayman Satopay

Reference

http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/tg/tcloth.pdf

https://www.livescience.com/28823-chinese-culture.html

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/architecture/

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/chinese-language/

http://www.cits.net/china-travel-guide/traditional-chinese-festivals.html

https://www.chinatravel.com/facts/typical-chinese-food.htm

https://www.chinadiscovery.com/ethnic-minority-culture-tour/ethnic-minorities-in-china.html

https://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/fabrics-fibers/chinese-textiles

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/culture/embroidery.htm