Understanding the cycles of fashion is important. Consumers are exposed each season to a multitude of new styles created by fashion designers. Some are rejected immediately by the press or by the buyer on the retail level, but others are accepted for a time, as demonstrated by consumers purchasing and wearing them.

Fashion cycle

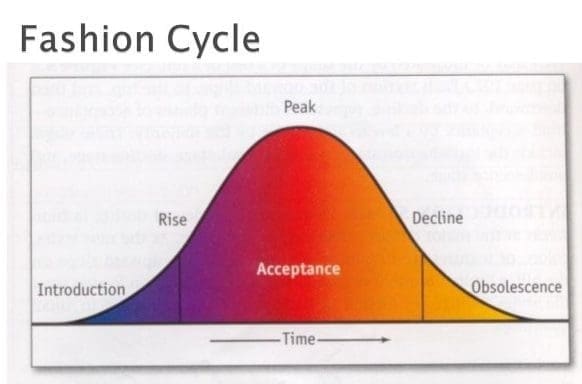

The way in which fashion changes is usually described as a fashion cycle. It is difficult to categorize or theorize about fashion without oversimplifying. Even so, the fashion cycle is usually depicted as a bell-shaped curve encompassing five stages. The cycle can reflect the acceptance of a single style from one designer or a general style such as the miniskirt.

Fashion cycle simply means the way in which fashion changes. Five stages are as follows:

- Introduction

- Rise

- Peak

- Decline

- Rejection

Let us know try and understand every stage of this life cycle.

- The introduction of a style

All the research and trials of ideas translate into styles and accessories that are then presented to the world. This is the stage where the creations are termed as ‘latest’ fashions and do not guarantee unanimous acceptance. This newness and style come at the cost of high price.

The works of reputed designers are backed by financial aid, materials required and also in terms of manpower in some instances. The production cost is obviously very high and these creations are afforded by a handful of people. This makes the production a small-scale viability, but will give the creator a lot of freedom and choice to experiment/

- The rise in popularity

In this stage, the latest fashion gets a nod from many a people, compelling them to buy, wear and display them in public. Couture designers try to sell their creations at a much lesser price and thus end up selling larger quantities.

This rise in popularity will go much higher during imitations and adaptations, thereby making the designers to modify a highly popular style and satiate the needs and price ranges of their customers. Other manufacturers may copy the trend with a less expensive fabric and detailing to sell them at a much lesser price.

- Peak of popularity

The demand created for a particular fashion may be so high that it may compel the manufacturers to copy and produce the designs at varying price ranges. The result could be flattery or resentment. This creates a thin line between adaptations and knock-offs.

If a fashion has to be mass produced, it must have a chance of mass acceptance. Thus, the manufacturers make a comparative study if the sales trends and forecasts thereby gauging the interest of their customers.

- Decline in popularity

Gradually lot of fashion gets mass produced, people get bored of the recurrence and look out for the next new thing. Consumers would still prefer wearing that style, but not at the same price. Retail stores put such declining styles on sale racks, hoping to make room for new merchandise.

- Rejection of a style

This is the last stage of fashion cycle and also the time of a new trend beginning to emerge. This creates disinterest in the minds of the customers and hence the trends are prone to rejection or discarding of a style, which is termed as customer obsolescence.

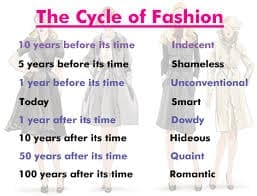

Fashion- cycle life span

All fashions follow the life- cycle pattern, but it varies with each fashion. Very difficult for fashion marketers to predict the life span. The length of time is determined by the consumer’s willingness to accept the fashion.

Fashion cycle lengths

- Flop cycle– No acceptance

- Fad cycle– Short acceptance

- Normal cycle– Medium acceptance

- Classic cycle– Continuing acceptance

The 5 Types of Consumer Adopters

Rogers presents a social system for adopters of recent innovation; the adoption of innovation varies throughout the course of the product-life cycle as shown in the diagram above.

- Innovators

- Early Adopters

- Early Majority

- Late Majority

- Laggards

1. Innovators

Innovators are the first customers to try a new product. They are, by nature, risk takers and are excited by the possibilities of new ideas and new ways of doing things. Products tend to be more expensive at their point of release (though some products do defy this trend) and as such innovators are generally wealthier than other types of adopters (though in some cases they may adopt products in a very narrow field and devote much of their financial resources to this adoption).

Innovators will often have some connection to the scientific discipline in which a new product is generated from and will tend to socialize with other innovators in their chosen product categories.

It’s also important to realize that innovators are comfortable with the risks that they take. They are aware that some products that they adopt will not deliver the benefits that are promised or will fail to win mass market appeal.

2. Early Adopters

Early adopters are the second phase of product purchasers following innovators. These tend to be the most influential people within any market space and they will often have a degree of “thought leadership” for other potential adopters. They may be very active in social media and often create reviews and other materials around new products that they strongly like or dislike.

Early adopters will normally have a reasonably high social status (which in turn enables thought leadership), reasonable access to finances (beyond those of later adopters), high levels of education and a reasonable approach to risk. However, they do not take as many risks as innovators and tend to make more reasoned decisions as to whether or not to become involved in a particular product. They will try to obtain more information than an innovator in this decision-making process.

3. Early Majority

As a product begins to have mass market appeal, the next class of adopter to arrive is the early majority. This class of adopter is reasonably risk averse and wants to be sure that their, often more limited, resources are spent wisely on products. They are however, generally, people with better than average social status and while not thought leaders in their own right – they will often be in contact with thought leaders and use the opinions of these thought leaders when making their adoption decisions.

4. Late Majority

The late majority is rather more skeptical about product adoption than the first three classes of adopters. They tend to put their resources towards tried and tested solutions only and are risk-averse. As you might expect, in general terms, this category of adopter has less money, lower social status, and less interaction with thought leaders and innovators than the other groups of adopters. The late majority rarely offer any form of thought leadership in a field.

5. Laggards

Laggards are last to arrive at the adoption party and their arrival is typically a sign that a product is entering decline. Laggards value traditional methods of doing things and highly averse to change and risk. Typically, laggards will have low socio-economic status and rarely seek opinions outside of their own limited social set. However, it is worth noting that in many cases laggards are older people who are less familiar with technology than younger generations and in these cases, they may still have a mid-level of socio-economic status.

Types of adopters

Theories of Fashion

Fashion involves change, novelty, and the context of time, place, and wearer. Blumer (1969) describes fashion influence as a process of “collective selection” whereby the formation of taste derives from a group of people responding collectively to the zeitgeist or “spirit of the times.”

The simultaneous introduction and display of many new styles, the selections made by the innovative consumer, and the notion of the expression of the spirit of the times provide impetus for fashion. Central to any definition of fashion is the relationship between the designed product and how it is distributed and consumed.

The Flow of Fashion

The distribution of fashion has been described as a movement, a flow, or trickle from one element of society to another. The diffusion of influences from center to periphery may be conceived of in hierarchical or in horizontal terms, such as the trickle-down, trickle-across, or trickle-up theories.

- Trickle Down

The oldest theory of distribution is the trickle-down theory described by Veblen in 1899. To function, this trickle-down movement depends upon a hierarchical society and a striving for upward mobility among the various social strata. In this model, a style is first offered and adopted by people at the top strata of society and gradually becomes accepted by those lower in the strata (Veblen; Simmel; Laver).

This distribution model assumes a social hierarchy in which people seek to identify with the affluent and those at the top seek both distinction and, eventually, distance from those socially below them. Fashion is considered a vehicle of conspicuous consumption and upward mobility for those seeking to copy styles of dress. Once the fashion is adopted by those below, the affluent reject that look for another.

- Trickle Across

Proponents of the trickle-across theory claim that fashion moves horizontally between groups on similar social levels (King; Robinson). In the trickle-across model, there is little lag time between adoption from one group to another. Evidence for this theory occurs when designers show a look simultaneously at prices ranging from the high end to lower end ready-to-wear.

Robinson (1958) supports the trickle-across theory when he states that any social group takes its cue from contiguous groups in the social stratum. King (1963) cited reasons for this pattern of distribution, such as rapid mass communications, promotional efforts of manufacturers and retailers, and exposure of a look to all fashion leaders.

- Trickle Up

The trickle-up or bubble-up pattern is the newest of the fashion movement theories. In this theory the innovation is initiated from the street, so to speak, and adopted from lower income groups. The innovation eventually flows to upper-income groups; thus, the movement is from the bottom up.

Examples of the trickle-up theory of fashion distribution include a very early proponent, Chanel, who believed fashion ideas originated from the streets and then were adopted by couture designers. Many of the ideas she pursued were motivated by her perception of the needs of women for functional and comfortable dress.

Following World War II, the young discovered Army/Navy surplus stores and began to wear pea jackets and khaki pants. Another category of clothing, the T-shirt, initially worn by laborers as a functional and practical undergarment, has since been adopted universally as a casual outer garment and a message board.

Thus, how a fashionable look permeates a given society depends upon its origins, what it looks like, the extent of its influence, and the motivations of those adopting the look. The source of the look may originate in the upper levels of a society, or the street, but regardless of origin, fashion requires an innovative, new look.

Article by- Sneha Savla